Why Rates Shouldn’t Rise as Much as You’d Think

The stock market sell-off this year, with the S&P 500 falling as much as 20% from its highs last week, ranks as the second-worst start to any year since the Great Depression. But consumer spending is strong, household debt is low, wages are rising and company profit margins are at multi-decade highs. So what is going on?

Rising rates have hit the stocks and bonds hard

Part of the problem is timing. The market hit its all-time high at the very start of the year, just before the Fed announced its pivot away from easy money and low rates in order to tackle the increasing inflation problem. Within weeks, it became clear that the Fed planned to raise rates rapidly, going from a floor of 0% to 0.75% already, with rates expected to reach more than 2.5% by the end of 2022.

Although, as Chart 1 shows, the market has known for a while that rates would need to rise in 2022. Heading into January, the 2-year Treasury yield had already risen from around 0.2% to 0.7%. Since then, it has climbed to over 2.7%, an increase of 200 basis points this year.

Longer-term 10-year Treasury rates have also roughly doubled so far this year, from 1.5% to a high of 3.1%. That has increased company borrowing costs and household mortgage rates, with mortgage rates increasing from 3.1% to 5.3% already this year, with data this week suggesting it has begun to slow the home sector.

Even bond portfolios have been hit by the speed and significance of rate increases, with long duration bond funds falling significantly too.

For comparison, back when the “Taper Tantrum” happened, when the Fed started talking about returning to a more normal rate policy after the Credit Crisis, rates only rose about 100 basis points, causing markets to sell off 5%.

Chart 1: Rates have risen dramatically this year, impacting valuations of stocks and bonds

Importantly though, Treasury yields have recently paused at levels around 3%, which is close to the expected target for Fed Funds at the end of the year. That implies the market thinks 3% is about as high as interest rates will likely need to get.

Rising rates to tackle inflation

The reason we have inflation is because all of the savings built up during Covid, including Covid benefits and lockdown savings, are now being spent. That has created a lot of demand for products and, since vaccinations became widespread, services.

Despite renewed demand, some workers have still not returned to work since Covid started. As a result, we also have shortages of labor which has started to increase wage costs.

Economies solve for too much demand by rising prices. Higher prices ration spending while also attracting more supply. However, rising prices also lead to inflation.

The war in Ukraine has only added to inflationary pressures, creating potential shortages in many commodities – from food to energy and metals. That has further increased the prices consumers are paying for oil and gas, especially in Europe.

So now, the Fed and governments around the world are trying to slow inflation by slowing demand, using interest rates.

There is research that shows this works. Raising interest rates causes consumers to think about saving instead of spending and leads companies to delay expensive investments. That reduces demand. However, as demand slows, so do sales and company revenues. Companies eventually cut prices to maintain sales, causing inflation to fall. Although, the research also suggests the economy slows around 12 months before prices fall.

Rising rates are a headwind to stocks

Rising rates also impact stock valuations.

At a very simple level, rising rates increase interest expenses, reducing profits. But they also cause investors, who can earn more interest on safe cash deposits, to demand stronger returns from all other investments too.

Starting with lower prices helps stocks have higher returns in the future. That’s why stock prices tend to fall as rates rise. Although growth in company earnings can also lead to stronger returns while you hold an investment.

One common valuation ratio encapsulates this well, the Price-Earnings (PE) ratio. For example:

- With a PE of 10, the stock price equals 10 years of earnings. That’s similar to earning 10% on a bond, where it would take 10 years of interest to pay for the bond (10x10=100).

- With a PE of 20, the stock price equals 20 years of earnings. That’s similar to earning a much lower 5% on a bond (5x20=100).

- Companies that are able to grow earnings can shorten the actual time to pay off an investment. That’s also why “growth” companies typically have higher PEs now.

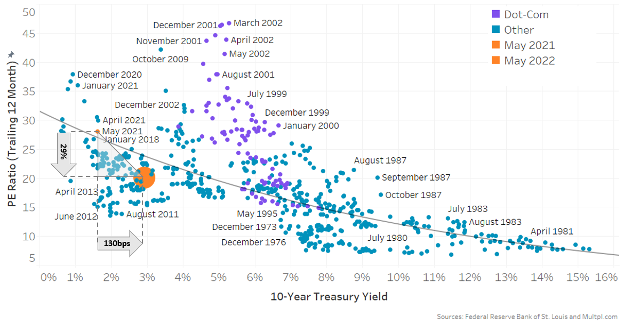

We can see how rate rises affect PE ratios in Chart 2. Historically, as 10-year rates rise, the PE ratio falls (grey trend line). In the past year, rates have risen very fast. Not surprisingly, the PE has fallen. In fact, the S&P 500 trailing PE has moved from the small orange dot to the large orange dot. We can account for the shift down and across shown by the triangle:

- Right to account for a 130-basis point change in interest rates.

- Down from a 28 to a 20 PE ratio. That’s a drop of 29%, made up of around a 20% fall in stock prices plus around a 9% increase in earnings.

Chart 2: Interest rates rising pushes PEs (valuations) down

That also leaves the current PE (large orange dot) below the long-term trend line, making stocks arguably cheap for a nearly-3% yield.

So why is the market still weak? There are two reasons the large orange dot could still move to “richer” levels:

- Earnings could fall (the dot would rise): The Fed is trying to engineer lower demand, which could reduce sales, which would lead to lower earnings, or company profits, in the future. That, in turn, makes the PE rise higher, even if rates stay the same. At the extreme, the economy slows enough to cause a recession, where employment also starts to fall, and spending could drop even more. That’s why some are talking about the impact of a potential recession in the future, although savings and activity levels now are far from recession levels.

- Rates could keep rising (and the dot would shift right): Alternatively, given how strong activity levels are, inflation could keep rising, despite interest rates reaching the current 3% levels. In that case, rates might need to rise further, as happened in the 1970s.

How high does the Fed have to go?

The chance that the economy needs rates dramatically higher than we have now to calm inflation seems unlikely, thanks to changing demographics.

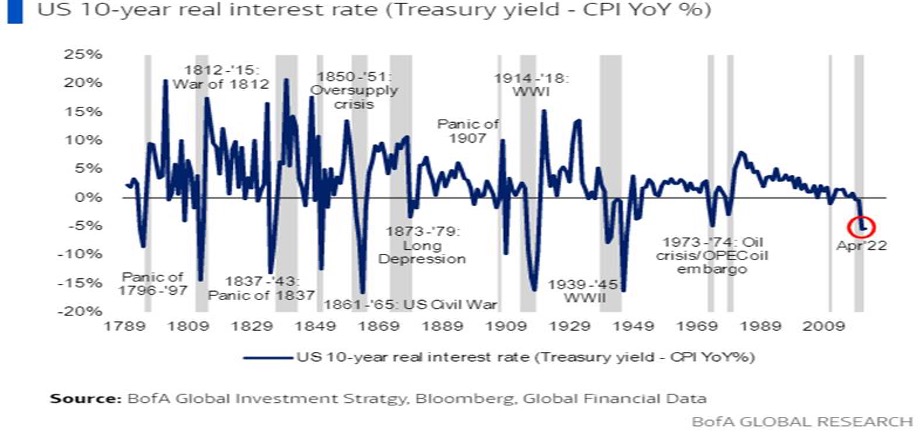

Looking at hundreds of years of data (Chart 3), it is normal for interest rates to be higher than the rate of inflation. That’s known as a positive “real” rate of interest.

A positive real interest rate is good for bond investors as it means they earn enough interest to buy more with their invested money than if they had instead spent the money right away. It also encourages people to save.

Chart 3: Negative real rates are rare and typically don’t last

With CPI inflation at 8.3% but fed rates below 1%, we currently have very negative interest rates. That might lead some to think interest rates need to increase above 8% to be back to “normal.”

However, that’s not true for a few reasons.

First, the Fed’s preferred inflation measure is the PCE, which is only at 6.6%. There are subtle differences between the CPI and the PCE. Basically, the CPI comes from a survey of what consumers are buying, while the PCE measures what businesses are selling. That means the PCE includes much more healthcare costs – which many companies cover – and which aren’t rising as fast as energy, food and car prices.

Second is the fact that longer-term inflation is likely lower than recent inflation rates – especially now the Fed has taken action to slow the overheating economy. We already see car prices falling, and oil peaked months ago (although pump prices are still rising). In the longer term, the expectation is inflation will come down, probably closer to 3-4%, especially if the jobs market cools, allowing wages to stop rising.

So as the Fed moves rates back up to more “normal” levels, inflation will also come down to more normal levels.

The big question is: What will normal inflation and interest rates be once all the current shortages are fixed?

The real neutral rate is around zero

Economists have coined the term for the rate of interest that is neither expansionary nor contractionary. The neutral rate is a real interest rate called “R-star” (R*).

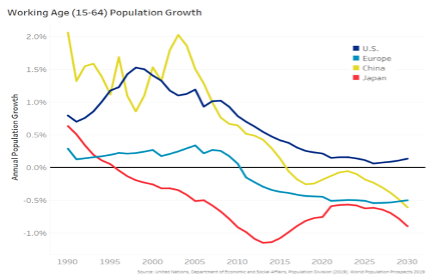

Data suggests the neutral rate of interest is related to the rate of growth in the economy. For example, looking at the green line in Chart 4 below, we can see that since the 1970s, even as the economy cycled through growth periods and recessions, the peaks that the 10-year interest rate reached have slowly fallen.

Other data suggest that interest rates have tracked the slowing growth of the economy (orange line), which itself seems to be driven by things like population growth (blue line) and the aging of the labor force (purple line).

Interestingly, the reverse happened in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Immigration and a higher birth rate caused strong population growth, adding to the workforce, increasing GDP growth and increasing the interest rate required to keep the economy from overheating.

Chart 4: An aging population slows the economy, output and the long-term rate of interest the economy can bear

At the end of the 1970s, the U.S. economy experienced an even stronger spike in inflation than what we have today, caused by energy shortages and price rises that led to a wage-price spiral. In order to slow that economy, Fed Chair Volcker famously raised short-term interest rates well above the “real” rate, as high as 20% in 1981, pulling long-term rates above 14%. It worked to slow the economy and reduce inflation, but it also caused two recessions along the way.

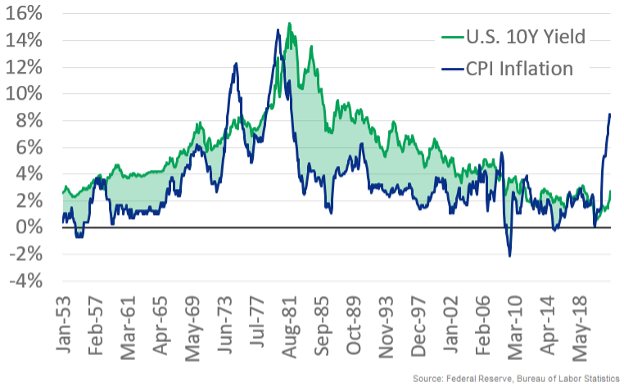

Since the 1970s, inflation has been consistently below 4% (Chart 5). As long-term interest rates have fallen (green line), so has the real interest rate (green shade). Since around 2005, the real interest rate has been close to zero, even as we experienced a slow recovery from the credit crisis from 2009 to 2019.

Chart 5: Real interest rates have fallen since the 1970s and are now, on average, around zero

That indicates the “neutral” rate of interest, or R*, is also pretty close to zero. In fact, the longer-term demographic trends in Chart 4 mean it might even be slightly negative – if not now – soon.

Importantly, this means the Fed won’t need to hike rates too far above the “normal” inflation rate to get inflation under control.

U.S. demographics are better than other major world economies

Interestingly, the U.S. is not the only country experiencing this fall in demographics and natural interest rates.

Looking at working-age population trends around the world (Chart 6), we see that Europe actually saw its workforce start to contract back in 2011, only a few years before the ECB adopted negative interest rates in Europe, which persist to this day, generating only weak economic growth.

Japan’s workforce has been shrinking for even longer, starting back in 1996. Not surprisingly, the Bank of Japan has been setting interest rates at or very close to zero for the decades in between, but that has not been enough to spur growth. In fact, the Japanese stock market total return index has only recently returned to its 1989 highs, leading some to believe that Japan actually had negative neutral interest rates the whole time (making the zero actual rate contractionary).

Chart 6: Most developed markets have declining workforces and weakening demographics

Arguably, the U.S. is in a stronger position than other major economies, with population growth expected to remain positive. But not by much. In reality, it seems likely all these economies, with their aging population and shrinking workforces, are destined for decades of slow growth, regardless of how low-interest rates get.

Although inflation is high right now, it’s because of Covid and the Ukraine war. Both, hopefully, will pass, and 3%-4% inflation a year from now seems possible if the economy slows to a more normal level.

In turn, that means the interest rate that keeps the U.S. economy growing slowly is likely much lower than we might currently be thinking. It might, in fact, be right around where bond rates are now.

And that’s good for stock valuations, especially after the sell-off we have seen already this year.

The views and opinions expressed herein are the views and opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Nasdaq, Inc.