Why Intelligent Ticks Make Sense

Some of you might have seen Nasdaq’s recent Intelligent Tick Proposal. We first mentioned intelligent ticks in 2017 as part of our Revitalize Blueprint, and again in 2019 in Total Markets. This newest proposal puts forward a more detailed, data-driven proposal for regulators and the industry to consider.

Two basic questions are: Why do intelligent ticks make sense? And how would they fix market structure?

This topic could solve a number of the issues we examined over the past year: including the fall in stock splits, inverted routing and rebates, and the increasing persistence of odd lot trades.

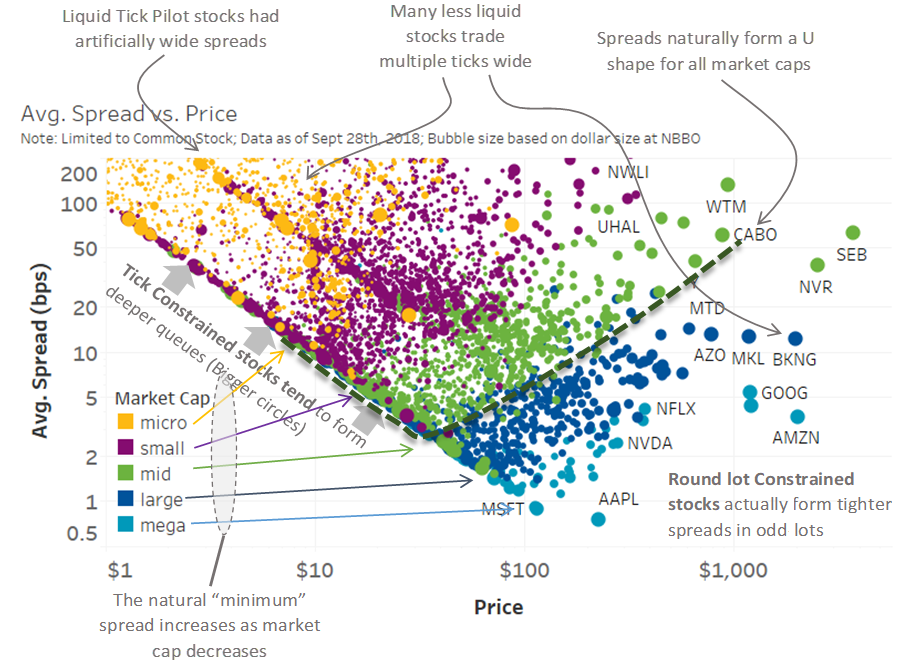

We’ve shown that spreads currently form a U shape

You may recall from earlier analysis of spreads and stock prices that we saw that spreads formed into a U shape across all market cap spectrums. That means spreads are more expensive for stocks with prices that are too low (tick-constrained), and also for stocks whose prices are too high (round lot-constrained).

Chart 1: The U shape for spreads is not what it seems when you analyze routing economics

Source: Nasdaq Economic Research

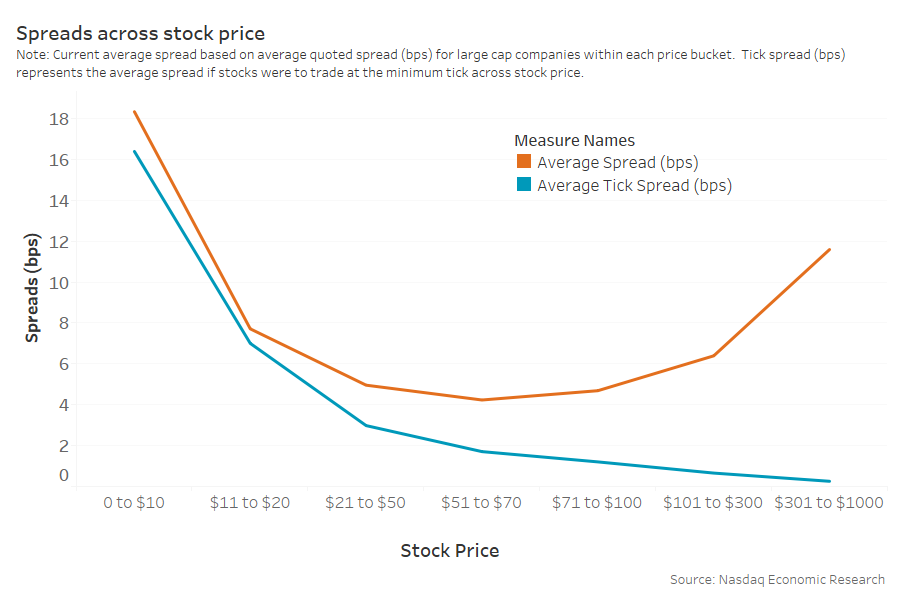

To summarize, what we find is that a one-cent tick size doesn’t fit all stocks, because as share prices change, the “return” for capturing spread changes, ultimately becoming economically meaningless as stock prices rise (see Chart 4). This has become a bigger problem over the last decade thanks to the lack of stock splits.

Fragmentation is currently used to solve for the large queue problem

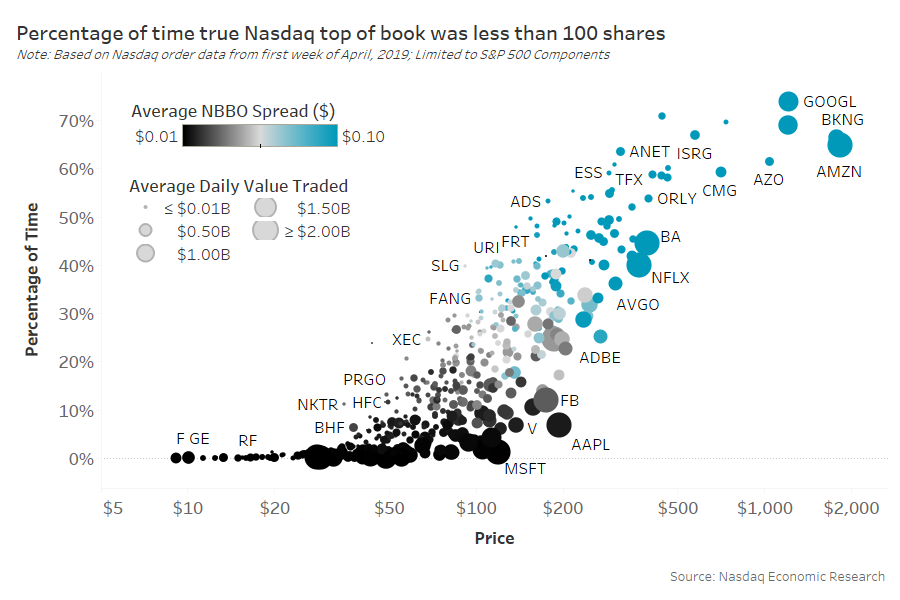

One of the things that tick-constrained stocks cause is long queues, as investors try to minimize spread crossing costs. The downward slope the data in Chart 2 shows that as share price falls (left side of the chart) queues get longer (vertical axis).

However as we’ve discussed more urgent traders often need to get fills more quickly. The economics of trading allow those traders to pay for queue priority by using inverted venues. While that increases market fragmentation and routing complexity, the data show that inverted market share increases (red color) as queue length rises and price falls. Not surprisingly, these are mostly the “tick-constrained” stocks from Chart 1.

In contrast, many higher priced stocks have queues that average well under 60 seconds and trade far less on inverted venues.

Reducing the tick (or raising the price) of these “tick-constrained” stocks would help them trade more like other stocks, reducing the complexity of queue priority decisions and also fragmentation, and also reducing spread costs for investors. Allowing a half-cent tick is a part of our Intelligent Ticks Proposal.

Chart 2: Inverted market share increases (red color) with queue length (vertical axis)

Source: Nasdaq Economic Research

There is an odd (lot) problem right now too

It’s interesting that spreads widen (in basis points as well as cents) on higher-priced stocks, causing the U-shaped spread curve in Charts 1 and 4.

This is related to another problem highlighted by the Wall Street Journal and by the SIP committees—odd lots have been increasing. Some have attributed this to algorithms finally becoming agnostic to round lots, a concept developed decades ago to reduce the trades that humans needed to process.

The problem has been accentuated by the lack of stock splits, allowing companies prices to drift much higher than century-long norms. MIDAS data confirms that odd lot trades occur more in high-priced stocks than low-priced stocks. Our own data found that the true NBBO is more likely to be an odd lot as prices rise (Chart 3).

However, in another study, we found that despite the odd-lots on the true NBBO, the average value able to trade was pretty consistent at the true NBBO across all similar stocks.

This indicates these stocks have become “round lot-constrained” on the SIP, with few traders willing to supply “round lot” liquidity at spreads comparable to other stocks (see Chart 5). For example, 100 shares in AMZN is worth close to $200,000, which is “block sized.” That’s disproportionately large given the average market-wide trade size is below $10,000, representing closer to just five shares of a $2,000 stock (an odd lot).

In short, the industry is starting to ignore the round lot conventions embedded in Reg NMS, but that’s not detracting from the inside market size.

Chart 3: Odd lots increase for higher-priced stocks (in conjunction with spreads increasing)

The SIP wants to add odd lots to the tape

The problem with having odd lots inside the NBBO is that not everyone can see the true best bid or offer. It’s also possible that some trades are missing the better fills that are available, especially in off-exchange venues which “peg” to the NBBO, as trades at the touch may be crossing much larger spreads than necessary.

One idea from the SIP Operating committee is to add unprotected odd lots quotes to the SIP (remember odd lot trades were added to the SIP back in 2013) as an additional field. However because they would be unprotected, it leaves open the question of whether it will actually fix the problem above. Commenters are clearly torn and raise the following points:

- Adding odd lots is good (because people will know where the true best price is).

- But not protecting them is bad (because people will not be obligated to trade with them).

- Although protecting them is also bad (because there may be immaterial orders making spreads infinitesimally tight (like one share x one share of AMZN just one-cent wide = 0.05bps).

- Which would in turn make best execution metrics for most orders incomparable across stocks and essentially meaningless (Chart 4).

Chart 4: A one-cent tick for all stocks (blue line) creates very different economics as prices change, ultimately representing a meaningless benefit for liquidity providers

This chart also highlights the difference between a tick and a spread:

- A “tick” is the allowable increment for quoting and trading stocks. Currently that’s set in NMS Rule 612 at one cent for all stocks, making the value of the tick shrink as prices rise.

- A “spread” is the difference between the bid and offer, which in contrast offers a more consistent return for spread capture (it actually has a U-shape as traders avoid posting round lots at infinitesimally small spreads, instead allowing stocks to quote “multiple ticks” wide).

The Nasdaq Intelligent Tick Proposal

Dynamic tick structures aren’t new. They have been used for years by many countries around the world, including all of the European markets, Hong Kong and Japan. Each attempts to ensure that the economic value of a tick is more consistent as stock prices rise. This is usually done by increasing the increment (cents or yen) required between valid bid and offer prices.

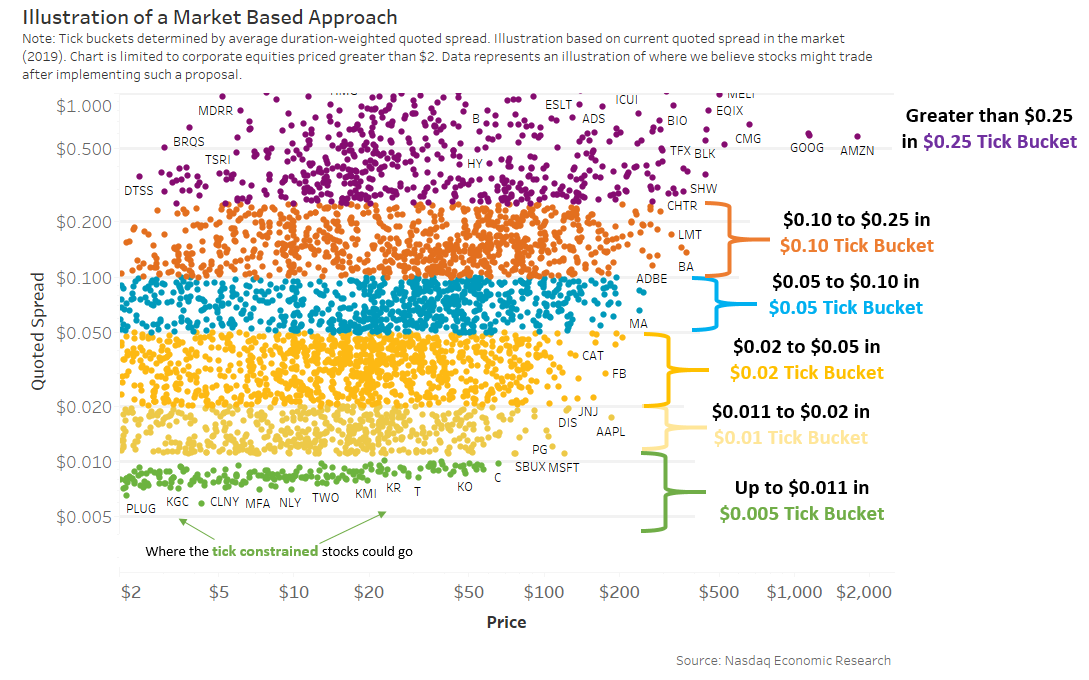

Our industry group’s Intelligent Tick Proposal differs from those structures in one important way: Rather than define spreads based on stock price or liquidity, we recommend setting ticks based on how each stock trades now. (We will discuss why the group decided to do this in a later post.)

The groupings in the proposal are shown in Chart 5, and range from a half-cent tick to a 25-cent tick. Each dot in the chart represents the current average NBBO spread for the stock (in cents, vertical axis) and the color shows the tick-group that would be assigned. Note that the quoted spread for dots in the half-cent bucket are estimated based on effective spreads we see today (where midpoint fills count as a “halving of the spread”).

Importantly all proposed “ticks” are narrower than the current “spread,” which means no stock is harmed.

Chart 5: Our proposal sets ticks closer to the natural level of spreads in the market

Our Intelligent Ticks Proposal could reduce costs and complexity

The Nasdaq-led industry group’s proposal should reduce costs and complexity across the spectrum of stocks:

- First, it would make the economic value of a spread more “equal” across the spectrum of stocks, which in turn should make queues more consistent lengths, simplifying routing and reducing fragmentation.

- Adding a half-cent tick for tick-constrained stocks should allow spreads in those stocks to fall, reducing trading costs for investors.

- There are also some results from the tick pilot as well as our own splits study that indicate that a wider increment on high priced stocks might stop quotes being “pennied” for uneconomic amounts, which may make the NBBO more competitive, and, in turn, actually make spreads tighter (even though the “tick” is wider than before).

In short, there is data that indicate costs should fall for low- and high-priced stocks, and queue sizes become more consistent, reducing the need to tune routers differently by stock price.

Intelligent Ticks – The Solution to Odd Lot Problem?

Ironically, this proposal might also fix the odd lot problem.

As we found in V-is-for Volume, the value on the bid and offer is proportionate to the relative spread. Widen the spread and depth increases. Narrow the spread and depth will fall.

Compare spreads on AMZN to AAPL and MSFT. All three stocks are very liquid with around $1 trillion market cap. But spreads on AAPL and MSFT are much tighter, at less than 1bps, compared to AMZN which trades over 3bps wide.

Not surprisingly AMZN is one of the stocks that has a true NBBO that is well inside the SIP NBBO most of the time. And when we compare the dollar value of depth on the true NBBO, it’s still higher for AMZN than MSFT, despite being an odd lot.

The problem is that nobody wants odd lots on the NBBO, as AMZN may start to trade one-cent wide but with just a few shares of (meaningless) depth.

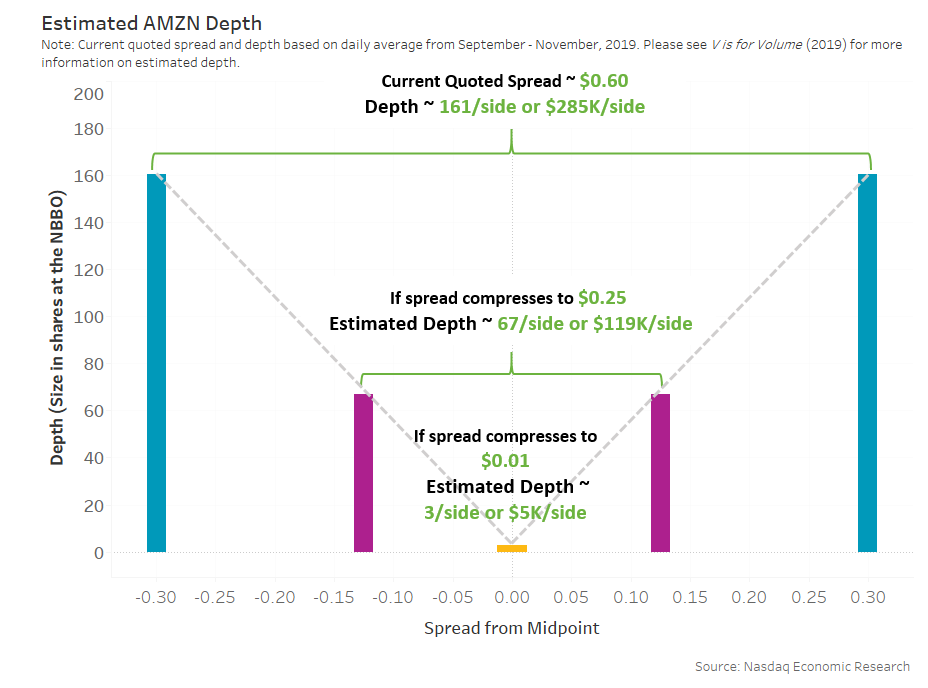

However, we can take what we learned in V-is-for-Volume to extrapolate how the combination of intelligent ticks and the elimination of round lots might work (see Chart 6).

- Right now, the NBBO for AMZN is around 60-cents wide with average notional value of $285,000 on each side of the NBBO.

- However, if all we do is add (and protect) odd lots, then it’s likely a one-cent spread will occur some of the time. Our data suggest not only would that represent a meaningless return for spread capture (just 0.05bps), but also the average depth at that spread would be just $5,000.

- In contrast, if we combine intelligent ticks with elimination of round lots, AMZN would have a 25-cent tick. With that minimum spread, the data suggest the odd lots would aggregate to a depth at the inside-quote of around 67 shares or $119,000. That’s over 10 times the average trade size and in line with current depth across large-cap stocks today.

On that basis, the spread would be worth adding to the SIP NBBO and the value of odd lots would also be worth protecting.

Chart 6: V-shaped supply and demand curve would ensure quotes were “worth protecting”

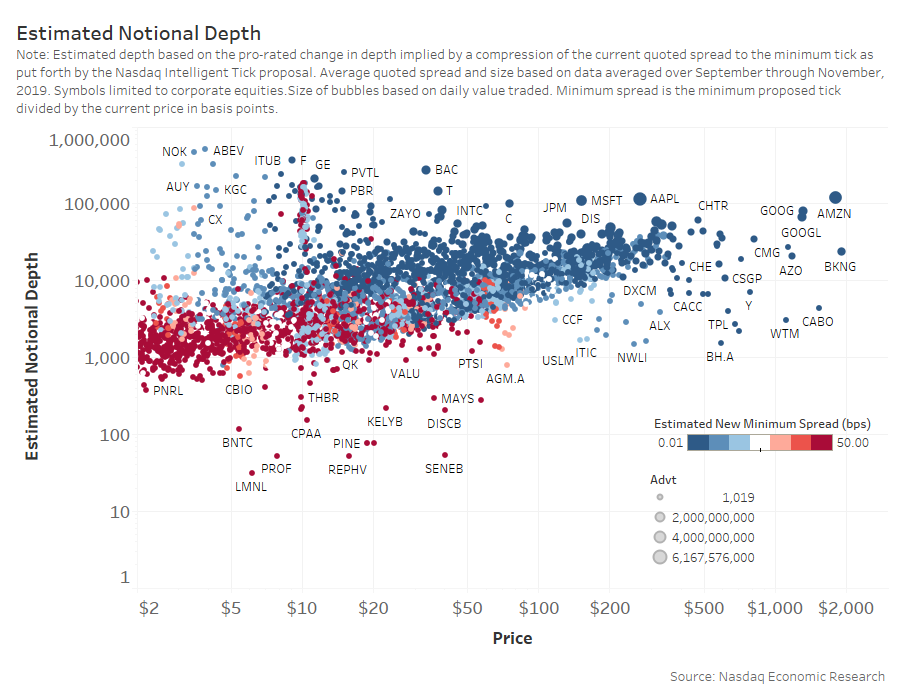

How would this affect depth and spreads for all stocks?

We can apply the same math across all stocks. Our estimates of NBBO depth in this new regime show:

- Tick-constrained stocks should see their queues and spreads reduced.

- Wide-spread stocks should see quotes aggregate at levels consistent with how the stock trades now (the dark blue color is roughly horizontal against the vertical notional NBBO size axis).

- High-priced stocks should see enough notional on the new NBBO that odd lots are worth protecting (note AMZN and GOOG are expected to have depth consistent with MSFT and AAPL).

- All stocks should trade with spreads that are attractive to makers while not being a penalty to takers. The blue color shows the minimum tick at around 1bps for all liquid stocks (large circles).

Chart 7: Our estimated spread and notional depth at the new intelligent ticks with no round-lots

It’s time to move our markets forward

It’s true that stock splits would probably have additional economic benefits:

- Studies suggest corporates could boost valuations and reduce trading costs with stocks splits.

- It would also keep trading even simpler if all stocks were closer to the same price (as more stocks could trade in the one-cent tick).

- It would encourage the removal of other cross-subsidies caused by cents-per-share commissions across disparate stock prices, such as SIRI vs AMZN.

- Companies can set their price at an optimum spread. As we know, each company has its own perfect stock price.

But getting hundreds of companies to split their stocks is hard (and we’re not just talking about BRK.A).

The proposals being discussed above would achieve many of the same goals: Equalizing the economics of spread capture, setting queues to more consistent levels, reducing fragmentation and routing conflicts and simplifying the SIP and NBBO, while tightening spreads and reducing the costs of trading.

It would “modernize” the markets. It may even help incentivize corporates to split their stocks back to a one-cent spread.

Let’s also remember that we are not the first market to consider relegating round lots to the dustbin of our manual trading history, nor would we be the first to add dynamic ticks.

Many markets already operate with intelligent ticks. We know it’s already working. Our markets need to get up to speed.