Tracking All-in Costs to Trade

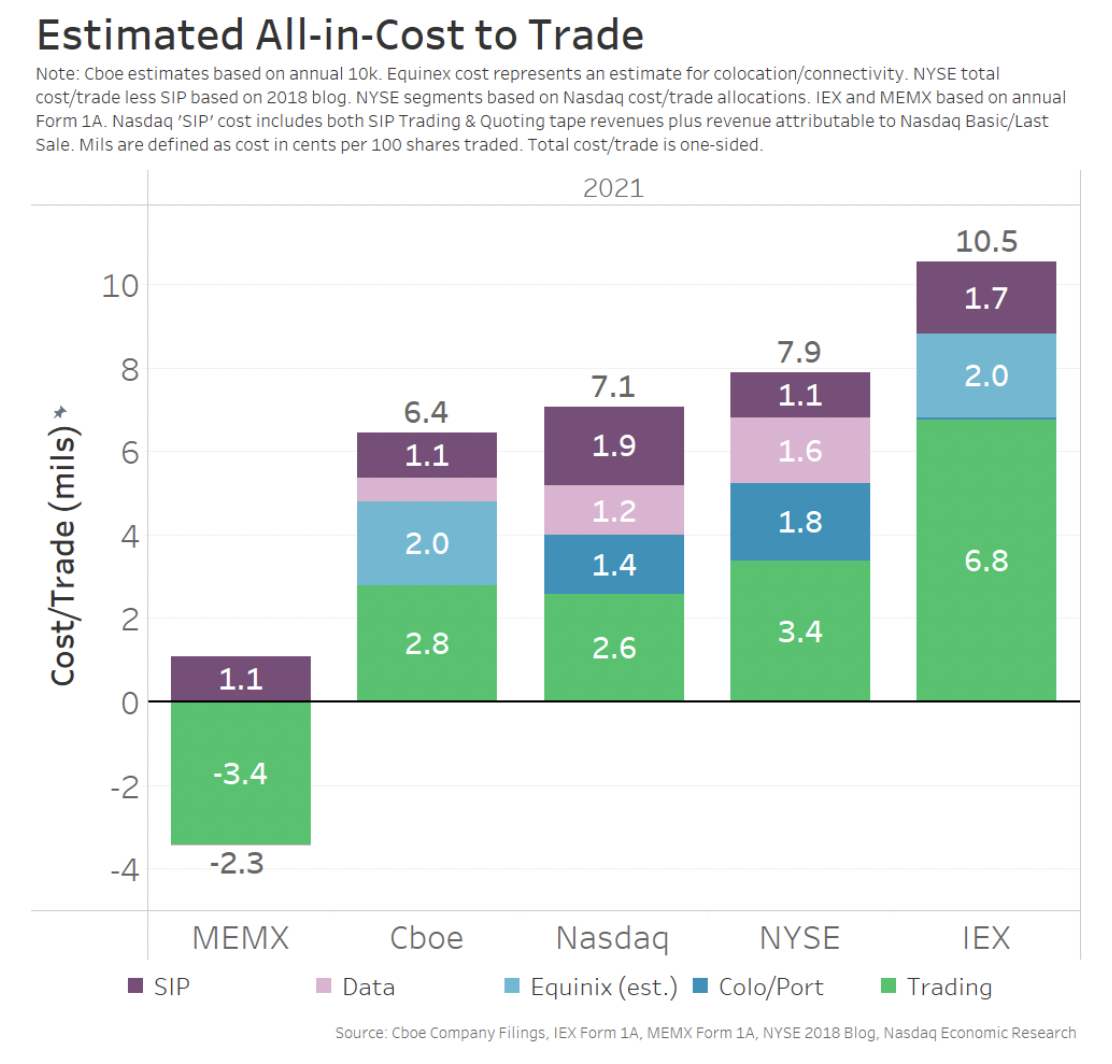

In 2019, we first looked at the all-in costs to trade on exchanges. Back then, we found that the average all-in costs ranged from around 7-9 mils before adding costs for the consolidated tape.

Today we update this data based on the latest data from 2021 regulatory filings.

Based on our estimates, we see that costs have fallen. The chart below shows all-in costs for those same exchanges have declined to between 5-9 mils (before SIP allocations), down from around 7-9 mils in 2019. Adding in the allocated SIP revenues, all-in costs add to between 6-8 mils per trade for the major venues.

Chart 1: All-in costs from 2021 are similar, regardless of how data, trading, and colo are priced

A few things stand out:

-

IEX remains the most expensive venue to trade and is still dependent mostly on trading revenues. However, it now earns significant data revenues from SIP for its D-Limit order, which pegs quotes to quotes from other exchanges. We estimate IEX spends less than $1.2 million per year to buy direct feeds from other exchanges and is able to parlay that into millions in trading and data revenues.

-

Some exchanges located in the Secaucus area don’t “officially” offer co-location. But trading customers still need to (and do) buy data center space nearby to trade on those exchanges. Consequently, we have estimated an equivalent co-location cost.

-

We were unable to parse Equity trading costs from MIAX regulatory filings.

-

MEMX stands out for running a negative all-in cost to trade. Of course, in 2021, MEMX was one of the newest U.S. exchanges and appeared to be running at a significant ($80m) loss which would not appear to be sustainable given their remaining net assets. We discuss what happened below.

Separating all-in costs to trade is economically efficient

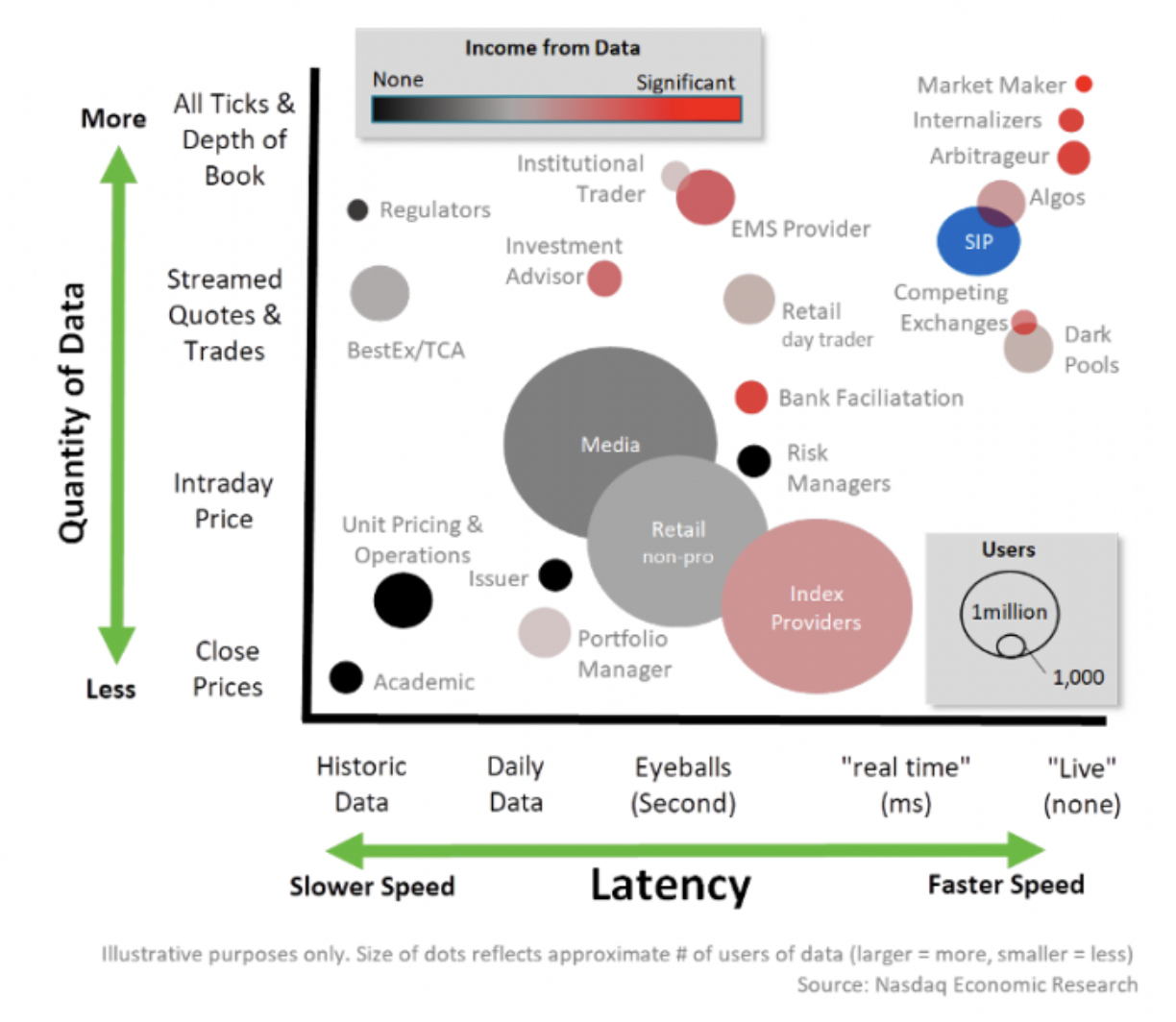

Of course, not everyone agrees that traders should have to pay for trading and data. But there are economic reasons to believe that markets are more efficient (with less waste) when consumers pay for trading and data but have more choices (and can choose what to consume).

For example, although many profit from trading, even traders have a wide range of different needs and benefits from exchanges.

-

A relatively small number of sophisticated participants need to trade at the speed of light, requiring investments in microwave technology and hardware that sits right by the exchange.

-

Some profit from trading in the dark using the prices from the NBBO, others try to profit from actually setting and capturing the NBBO spread, while others profit from crossing exchange spreads when arbitrage is available.

-

But the majority of traders are humans. It's not fair or efficient to make them share in the costs of microwave infrastructure with ultra-low latency that they do not want or need.

It also turns out that lots of market participants want to know what prices others are trading at. Some profit from market prices without trading at all. That includes media companies, index providers, custodians, prime services businesses, order managers and risk system providers.

And, of course, there are those who don’t profit from data but still need it — like educators and regulators.

Chart 2: Markets have many different users, some of whom profit without even trading

Charging everyone an equal price for all products, regardless of what they want, would be unfair and inefficient. It would create what economists call a “deadweight loss” – where some pay too much, and others don’t consume – even though another group profits from the same “universal” fixed prices.

Acknowledging this, even the consolidated tape has developed multiple rates that provide more cost-effective benefits for different use cases – less for inactive retail, more for professionals, and even more for computers that trade a lot (and a lot faster).

It makes economic sense and maximizes utility to not force some investors to pay for products they just don’t want.

Free isn’t fair (or efficient) either

Another way to look at this is to think about the distortions that “free” things create.

We have shown in prior research that market data prices generally rise in-line with market share, implying that those with “free” data are mispricing their data and cross-subsidizing their operations with revenues from other areas. Chart 1 would seem to confirm that can happen.

We also see that competition seems to cap fees on smaller markets and lower levels so that the “per-trade” price ends up roughly the same.

Chart 3: Proprietary data costs increase with market share

Economically, the problem with “free stuff” is it results in overconsumption. That, in turn, costs the companies more to produce more, creating a misallocation of resources.

Over time, the U.S. stock market seems to have proven this to be true. Those who have touted “free” stuff have moved to reduced mispricing within their product ranges. For example:

-

In 2022, to offset the significant losses on trading we saw in Chart 2, MEMX introduced fees for membership, connectivity, and market data. In fact, in its 2021 filing, it noted that “[p]rior to January 3, 2022, MEMX did not charge fees for connectivity to the Exchange...to eliminate any fee-based barriers…when MEMX launched as a national securities exchange in 2020, and [it was successful attracting] a significant number of Members [who are now] directly or indirectly connected to the Exchange.” Importantly, MEMX data costs are now in-line with more established markets based on its market share (Chart 3).

-

In 2021, IEX added fees for connectivity and market data. In IEX’s proposal for connectivity fees, it highlighted the economic inefficiencies created by providing services for free, noting “some users request and are assigned more Order Entry Ports than they use. For example, during May 2019, 100 Members did not send orders through one or more assigned Order Entry Ports, representing approximately 25% of all assigned Order Entry Ports,” later adding that “IEX also believes the proposed fee is a reasonable means of encouraging Users to be efficient in the number of logical ports they reserve for use.”

Fair and efficient markets are hard to do right

Although today’s analysis is mostly an update of previous work, we see again that free isn’t fair – or efficient. Nor can loss-leading last without adding more costs to the industry.

For the same reason, consolidated data is difficult to price in a way that protects investors and maintains fair and efficient markets. Instead, equal (some might say non-discriminatory) prices actually discriminate a lot – as they force some consumers to pay for things they don’t want and won’t use.

Market-wide revenue allocation formulas can also distort market quality – as venues engineer ways to copy the prices of others for profits – sometimes with strong margins. That’s not fair to the participants setting those prices. Nor is it an efficient way to incent a competitive NBBO.

Most importantly for today, though, is that despite more new venues and more fixed costs, overall costs per trade have fallen since we last looked at this. And that’s (still) good for investors.

Michael Normyle, U.S. Economist at Nasdaq, contributed to this article.