The 2023 Intern’s Guide to the Market Structure Galaxy

It’s that time of year again when many of us have interns just joining the desk. So, over the next few weeks, we’ll update and re-share our introductions to markets and trading for interns. Each has plenty of links for interns looking to take a deeper dive into the topics mentioned.

For those of you who have worked in the market for years, sit back, relax and enjoy the refresher—you never know when an intern might ask a question about the basics.

What are stock markets for?

All markets, even the ones you shop in for groceries, have a pretty simple underlying purpose: to bring together buyers and sellers. Doing trade in a centralized way allows consumers to compare prices and producers to advertise to more customers at once. Economically it’s a win-win.

Stock markets add another dimension, as they also provide companies with access to investors. Cash from investors allows companies to grow profits, which in turn provides income back to the investors.

The markets are an ecosystem

Whether centralized or not, markets work best with a diverse ecosystem of participants, each with their own specialized role to play in buying, selling and valuing stocks.

Chart 1: The stock market ecosystem

Listing exchanges bring all participants together

Exchanges play a central role in stock markets, literally. They are (by law) open to everyone and create a “single market” for issuers, investors and liquidity providers. They allow companies to find investors and traders to all interact at the same prices despite each wanting to hold shares for different lengths of time and based on different trading signals.

For example, an arbitrageur might see ETFs dislocate from stock values for a few seconds, but a mutual fund portfolio manager may decide to buy a stock to hold for two years or more based on expected growth in sales.

Exchanges are also unique in that they usually advertise prices allowing other investors to see buyers and sellers and see the best prices in the market. That provides what economists call “positive externalities.” It helps all traders keep prices as efficient as possible while creating tighter spreads that reduce transaction costs for all investors (even those who don’t trade on an exchange). It also lets everyone see whether the market is up or down at any instance, allowing them to modify investments, buy dips and sell peaks with more confidence.

Getting to the heart of the issuer

Companies, also called “issuers” because they issue stocks, are critical to public markets. Without issuers joining public markets, there would be fewer companies to invest in, fewer dividends for investors with 401k accounts, and fewer securities to hedge and trade.

Public markets provide more listing standards, and SEC rules require corporate accountability via quarterly accounting statements and other disclosures. That tends to make public markets more transparent and relatively safer for investors. Because of that, most funds are limited to investing in so-called “listed” stocks.

Only a few exchanges actually “list” stocks, which requires having listing rules and ongoing surveillance of the companies. Only those listing exchanges host initial public offerings (IPOs). But thanks to pro-competition rules, there are around a dozen more exchanges that are just markets for trading.

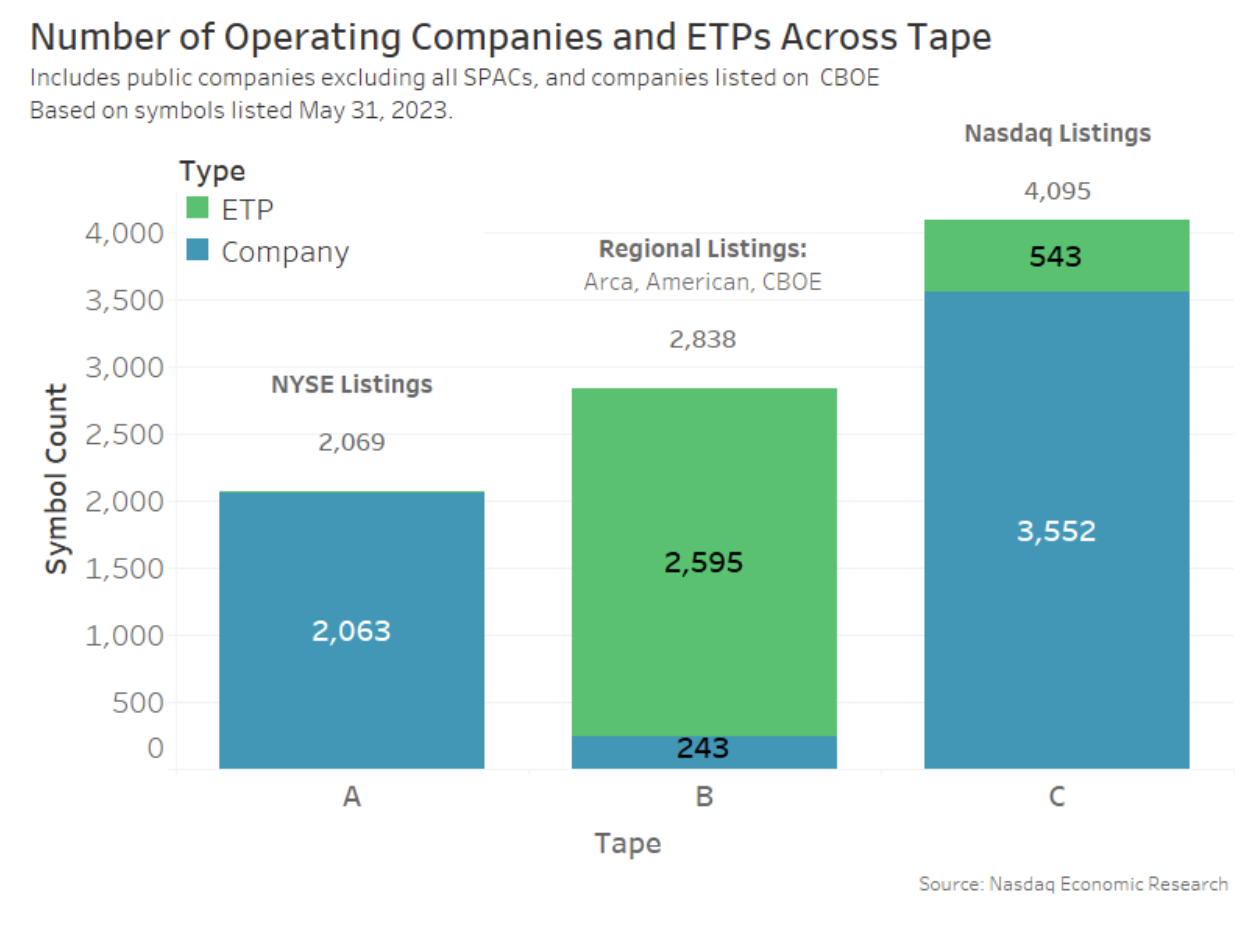

Where a company is officially listed also affects what “tape” its trades are reported on. A term that relates to how stocks traded in the past, when trades were literally printed onto ticker tape, there are still three “tapes” that publish trades and prices:

- Tape A is for all NYSE listings (regardless of what exchange the trade actually occurs on).

- Tape C is for all Nasdaq listings (regardless of where trades occur).

- Tape B is for all other exchanges, including the Cboe exchanges and NYSE Arca (which predominantly list ETFs) as well as NYSE American (which typically lists small companies).

One good reason for this is that primary exchanges are also responsible for opening and closing trading in their listings each day. The closing auction, the last “official” trade of the day, is especially important because it sets the official prices used for index funds to trade and actively-managed funds to invest customer cashflows.

Chart 2: Number of U.S. companies on each “tape”

The day of an IPO is important for a company and investors. Typically bringing a company public allows some bigger investors, like workers’ 401k plans, as well as lots of little “retail” investors to buy their stock.

Having more investors can boost a company’s valuations and increase trading activity as investors know they can sell at any time.

During Covid, as interest rates fell to near zero, we saw a multi-decade record for IPOs, with over 311 new company listings and even more SPACs. However, in 2022, rising interest rates made stock prices fall, resulting in a dramatic slowdown in the IPO market.

Chart 3: 2021 was a record year for IPOs, but as rates rose in 2022, the IPO market slowed

U.S. equity markets aren’t the only choice for new companies, though. Our public markets have to compete with private markets, OTC markets (formerly including pink-sheet and bulletin board stocks) and international stock markets for listings.

That said, the U.S. stock market is the largest source of equity capital in the world. At the end of 2022, the U.S. listed market had nearly $55 trillion in market cap and trading of around $444 billion each day.

Issuers need investors

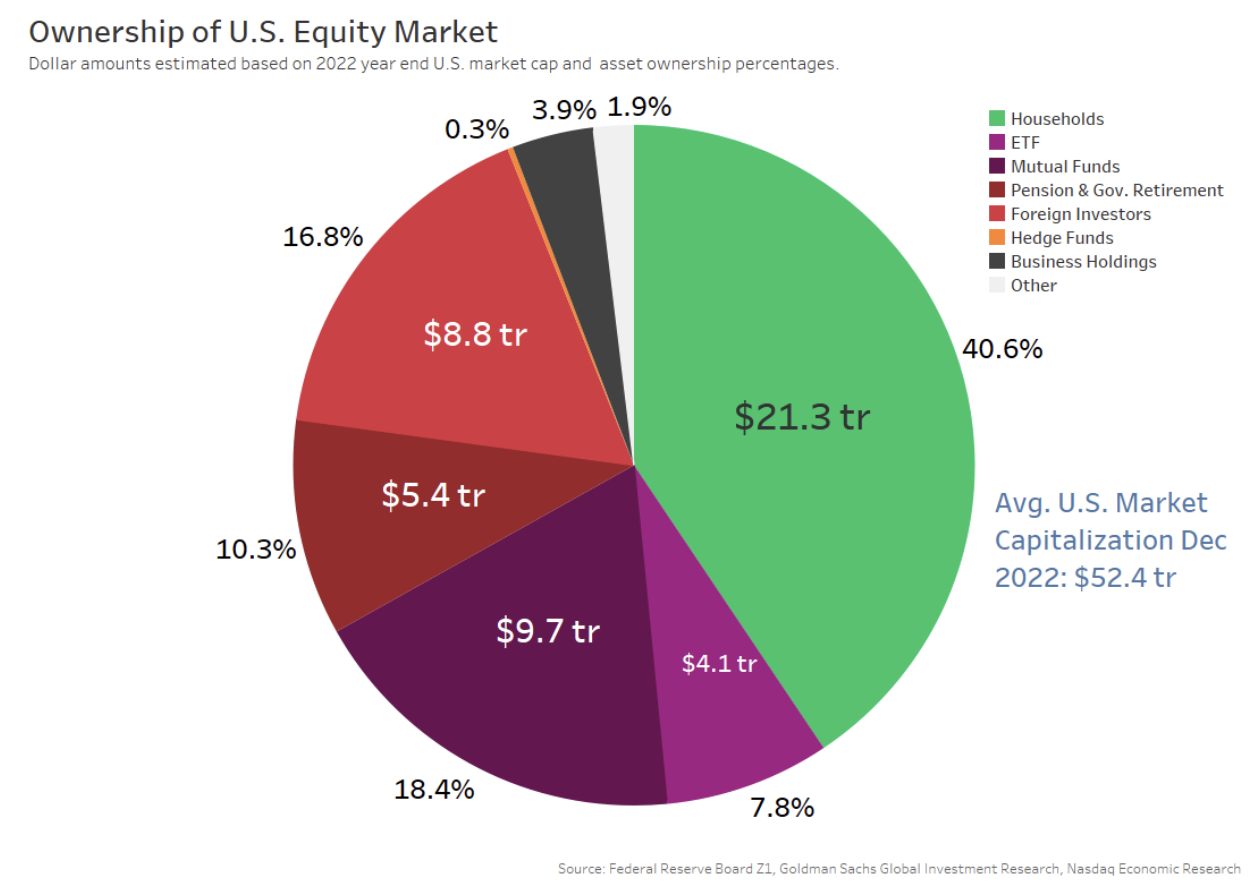

In order to raise capital, issuers need to attract investors. Long-term investorscome in two main flavors:

- Mutual funds and pension funds (also called “institutional investors”) are where a professional manages a portfolio for a group of individual investors.

- Retail investors (or “households” in Chart 4) can execute trades and manage their own portfolios direct from an app on their phones.

Data suggests they both have roughly the same amount of capital to invest (approximately $20 trillion each).

Chart 4: Who owns shares (based on year-end 2022 data)

All investors are trying to maximize their investment returns. Many mutual funds will research stocks to try to find companies that will grow revenues the fastest, pay the best dividends, have the best profit margins, or offer the best value (however you define that).

These funds, and the professionals managing them, provide an important role in what we call “price discovery.” Their buying makes good companies’ prices go up, while companies with less rosy outlooks see their prices fall as investors sell. It is part of what helps markets efficiently allocate capital. But actively picking stocks that outperform is also how portfolio managers beat the market.

Other portfolio managers run index funds. These try to buy every stock in an index, usually at market weight. These funds save costs, as they do less research and much less trading. They are also relying on the market’s overall efficiency to ensure the prices they pay are not inefficient.

Data comparing returns of index and active funds suggests the market is very efficient. Recent data also shows assets in index funds are now larger than in actively managed mutual funds.

Retail investors also want to maximize investment returns or at least minimize losses. And app-based trading has allowed retail to trade more easily and cheaply than ever before. In fact, during Covid, we saw retail investors trade even more than usual, thanks to the introduction of commission-free trading and increased savings caused by Covid. The level of activity has continued, although retail has been selling stocks as the market fell. Despite that, retail net buying into ETFs, a form of mutual fund that trades on exchange, has continued to accumulate.

Issuers and investors need banks and brokers

Most of the time, issuers and investors need banks and brokers to help them enter and exit the market.

Banks have many direct relationships with issuers and mutual funds. They research and often lend to companies. They also research stocks and execute trades for mutual funds, sometimes using their own ATSs (Alternative Trading Systems, such as dark pools). So, they contribute to both capital formation and liquidity.

Ahead of an IPO, brokers will canvass investors to assess interest and help price and allocate shares in the IPO. The IPO is known as a primary market.

Then, as investors buy and sell stocks to change their portfolio holdings in so-called “secondary” markets, they usually need brokers to “work” their orders over time.

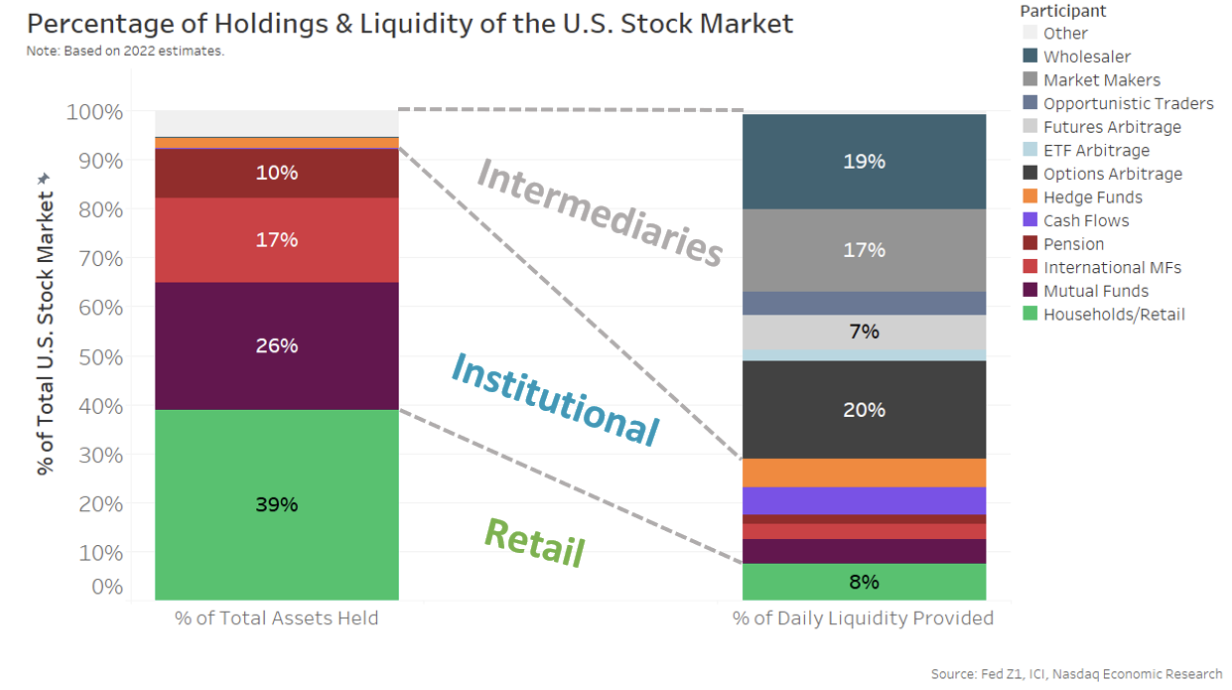

Investors need shorter-term traders to keep markets efficient

There is not always another investor looking to sell when a new investor wants to buy. That’s where short-term traders – from hedge funds and banks to market makers and arbitrageurs – help.

Although each has different investment objectives, they all play a critical role in keeping markets efficient and liquidity cheap. Our estimates also suggest they make up the majority of trading (Chart 5).

Chart 5: Investors have the majority of assets; intermediaries do the majority of trading

Market makers don’t hold stocks for long, but their specialty is being both a buyer and seller at the same time. Creating a “two-sided market” in each stock ensures investors can trade regardless of whether they are looking to buy or sell. In return, market makers hope to earn the spread, or the difference between the bid and the offer.

Arbitrageurs help futures and options track their underlying asset prices very well. Our research shows that ETFs trade in line with their portfolios’ net asset values even if the ETF doesn’t trade. Thanks to sophisticated statistical hedging strategies, many ETFs are actually cheaper to trade than their underlying stocks.

Hedge funds, in contrast, tend to hold long and short positions at the same time. Their strategies often keep similar stocks, sometimes called pairs, efficiently valued. That helps keep markets more efficient, adding selling to a buyer of one stock by buying a hedge from a seller of another stock. Research even shows that short sellers help keep markets efficient by adding sellers to overbought stocks.

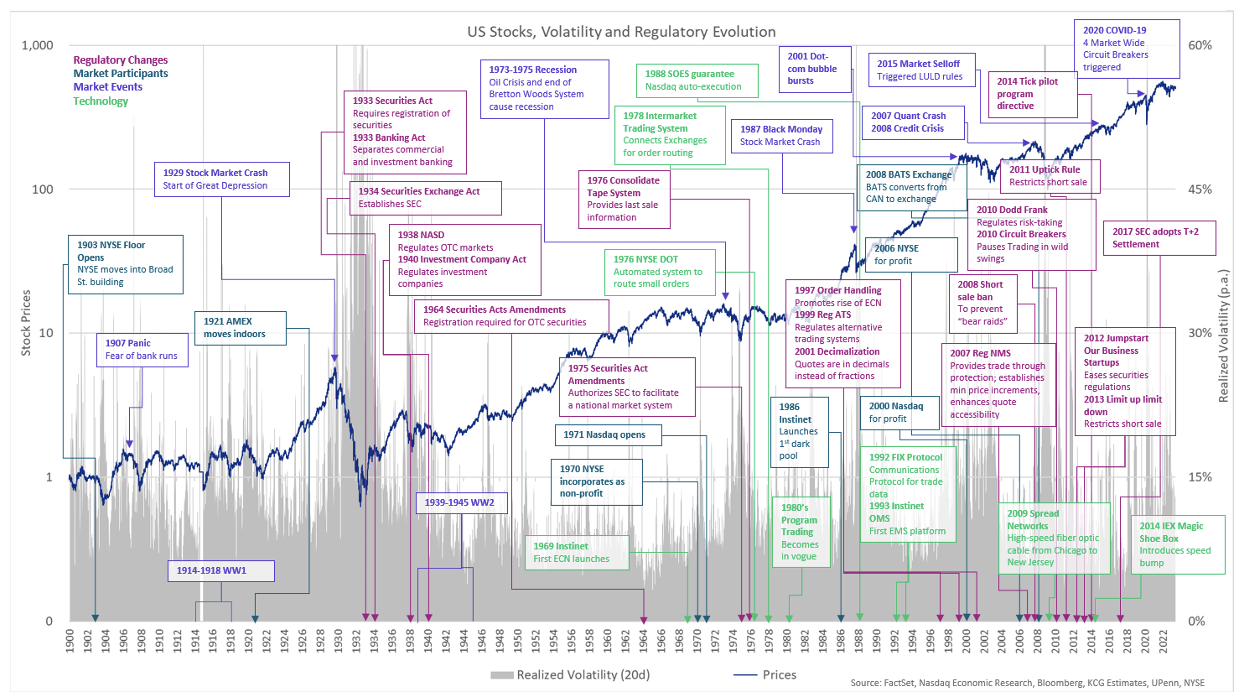

Markets rules have evolved over time

Stock markets have rallied and crashed multiple times in history. Often, following bear markets, rules are changed to protect investors. That’s exactly what happened after the largest bear market in U.S. history, which followed the U.S. Depression, where stocks fell over 85% from their highs as unemployment reached 24.9%.

In the decade that followed the depression, U.S. markets saw the introduction of a number of new rules to protect investors:

- Securities Act of 1933: Established rules for IPOs so that investors would have information on which to base their investment valuations.

- Banking Act of 1933 (also known as the Glass-Steagall Act): Separated commercial banks that lent homebuyers money and investment banking that traded stocks and bonds. To this day, insurance on bank accounts (FDIC) and brokerage accounts (SIPC) is different, although Glass-Steagall was repealed, allowing today’s mega-banks to do stock broking and banking for their customers.

- Exchange Act of 1934: Established the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to regulate stock and options markets and set exchanges as self-regulatory bodies (SROs) responsible for policing their own listed companies and trading rules.

- Formation of NASD in 1938: The National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD) regulated the trading of stocks that were not listed on exchanges. It has since become Nasdaq (trading) and FINRA (broker regulation).

- Investment Company Act of 1940: Set all the rules that mutual funds (including ETFs) need to follow, including safe custody of assets and limits on leverage.

Chart 6: Market rises and falls (log scale)

Setting up for consolidation and fragmentation of trading

Another significant regulatory change happened in 1975 with the Securities Act Amendments. Those rules set up what we now call the National Market System (NMS). Perhaps most importantly, brokerage commission rates were deregulated by the SEC, a move that drew significant criticism as Wall Street cried May Day. However, in a trend that would play out again over the following decades, lower costs led to rising volume that has long since made up for lower fees.

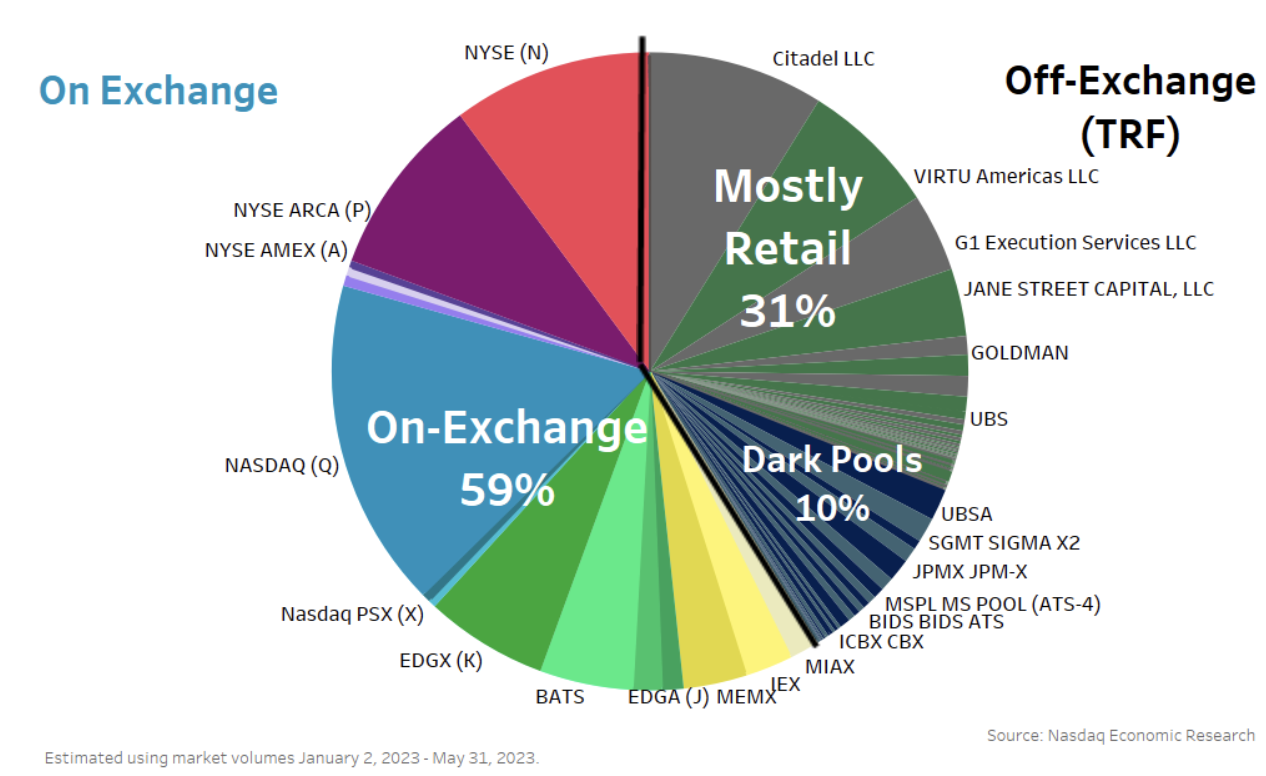

Then in 1994, Congress passed the Unlisted Trading Privileges Act of 1994, which allowed any exchange to trade any ticker—regardless of where that stock was listed. Today there are 16 exchanges and more than two dozen dark pools, all of which can trade any listed U.S. stock.

Although Instinet launched the first dark pool in 1986, Reg ATS didn’t set consistent rules for dark pools to trade in in 1999.

Chart 7: Today’s market is fragmented, with many venues able to trade any stocks they want

Market automation also started in the ‘70s

It probably seems hard for an intern to believe, but as recently as the 1990s, most stocks were traded in person, in “pits” or at “posts” on the floor of an exchange, with each trade written down on tiny pieces of paper that were taken back to the office to be processed for customers. The next day, interns would probably join “runners,” delivering physical stock certificates from the seller’s broker to the buyer’s broker.

Some floors do still exist today, but the U.S. market started to automate back in 1971, an event that ultimately created Nasdaq. Although Nasdaq’s first “data centers” had tape drives, monochrome cathode tube screens, sideburns and plaid trousers. A lot has changed since then.

Exhibit 1: A Nasdaq data center in 1971, the year the company’s electronic exchange began operating

With most floor-based markets, all investors would see was a ticker tape of historic trades, literally a rolled-up piece of paper with typing on it, well after the trades had actually happened. Although even today, the industry refers informally to the record of all quotes and trades as “the tape.” You might even hear a trader still say a trade has “hit the tape,” which means it is now on the screen and in the database.

Moving from automated quotes to trades

In its first iteration, the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD, now FINRA) built a system for market makers in OTC (generally micro-cap) stocks to electronically update their bid/ask quotes. That became the NASD Automated Quotations (hence the acronym NASDAQ).

Exhibit 2: One of the early Bunker-Ramo computer terminals used to make and see quotes

Over time, as computers improved, more data could be shared more easily. This benefited investors and traders who could not necessarily see what was happening on other human trading floors.

The main data innovation in the 1980s was the creation of a real-time “Level 2” data feed. More than simply providing the best bid and offer, Level 2 showed all market maker quotes at different prices below the bid and above the offer. What is now called “depth.”

Exhibit 3: The quote montage from the Nasdaq Workstation II in the late 1990s, showing depth (Note prices are in fractions of a dollar; some bonds still trade in fractions today)

Automating executions after the 1987 crash

Another big market crash happened in 1987 when the S&P 500 fell more than 20% in one day. Back then, there were no Market-Wide Circuit Breakers or other guardrails to slow markets down and allow buyers to assemble.

In the aftermath, it was discovered that many market makers were unable or unwilling to trade even though buy prices could be seen on the screens. Shortly after, the process of matching trades was also automated, creating what we now call “actionable quotes.” Although in their early forms:

- The Small Order Execution System (SOES) automated executions up to a maximum of just 1,000 shares to protect market makers from large market movements.

- The SelectNet system allowed traders to create locked-in trades—although it worked a lot more like email for trading.

Lower costs drive liquidity and activity into the 2000s

However, that set the scene for a market that looks more like what we know today – where almost all trades are executed electronically. And as the market adopted computerized trading, important new rules were introduced:

- 1997 - Order Handling (Manning) Rules: Now that customers could join the same bid as market-makers, manning required Brokers to put customer orders first. That made it easier for investors to trade with each other and capture more spreads.

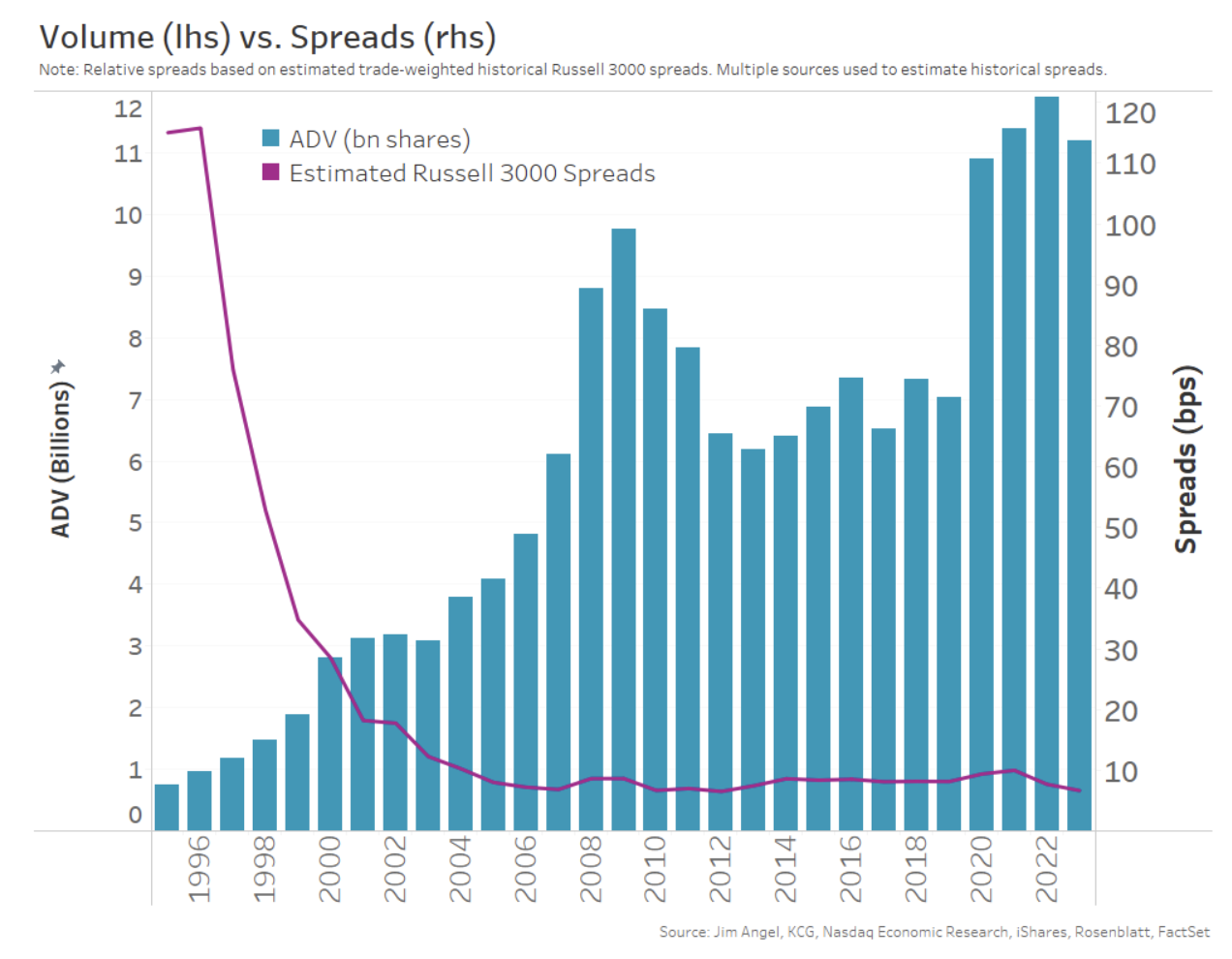

- 2001 - Decimalization led to quotes being in cents, which we see today, not fractions, as we saw above. That followed fractional ticks reducing from eighths to sixteenths in 1997, all of which made spread costs much smaller and market-making less profitable.

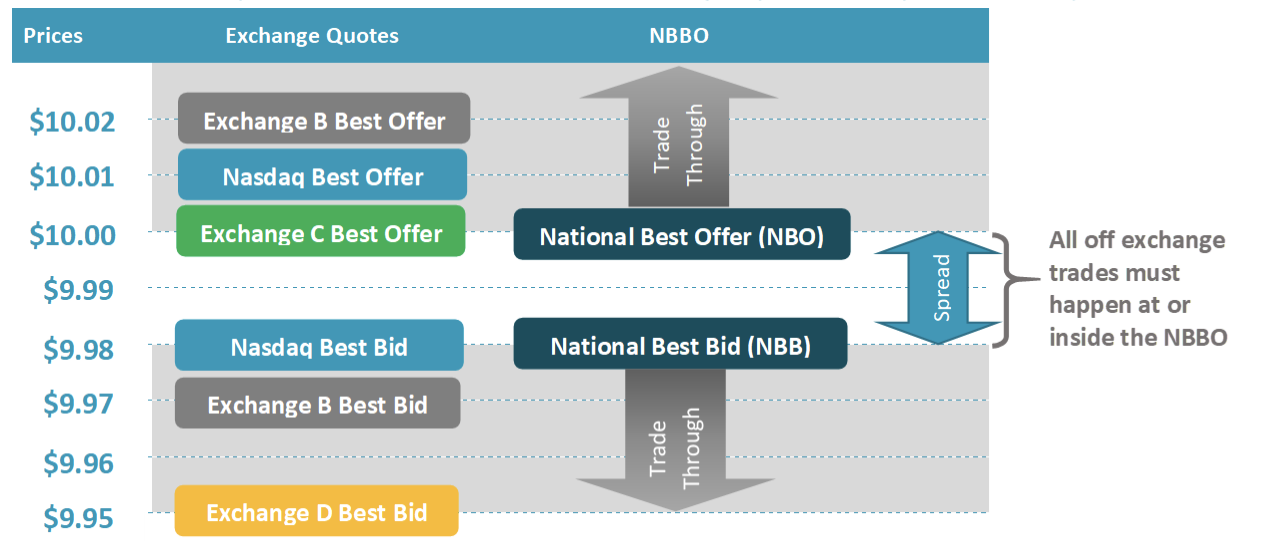

- 2007 - Reg NMS mandated many things we take for granted today: quotes that are publicly available and actionable, prices that can be consolidated in real-time to create an NBBO and an interconnected market that helps investors always trade on markets with the best prices.

As a result, market-making became more automated, and trading got cheaper. From 1995 to 2005, markets saw spreads decline 90%, and liquidity increased tenfold.

Chart 8: The impact of market-wide automation cut trading costs and boosted liquidity

Because spreads are so tight, and trades are all reported electronically now, newer SEC rules have been focused on changing ticks once more, as well as adding more data and smaller trades to public feeds.

Trading at the speed of light

This all means that over the past 50 years, trading has gone from human speed to computer speed to the speed of light.

Computerized trading has led to fewer manual errors, faster processing and cheaper trading. It has also made trading faster. A lot faster. Consider that a human blink takes around a quarter of a second (that’s 250 milliseconds). Light travels from one U.S. exchange to another around 100 times faster, and the computers that compile the consolidated quotes for the public take even less time (currently around 0.02 milliseconds, or 20 microseconds).

All of which is to say, arbitrage happens very quickly, and markets are now very efficient.

Chart 9: Distances between trading centers at the speed of light

Where do prices come from?

In reality, almost all trading in U.S. stocks is done in data centers in New Jersey these days.

So that all investors know which exchange has the best bid and which has the best offer, a single unified national best bid and offer (NBBO) that gathers the best prices from all venues is available to all investors.

This forms the “tape” that we talked about earlier.

Chart 10: SIPs compile the NBBO based on all the exchanges quotes in a specific security

Given there can only be one unified NBBO, the responsibility for creating it has historically rested with each stock’s “primary listing” exchange. That’s why, today, we have three tapes (as Chart 2 shows) calculated electronically by Securities Information Processors (SIPs).

Market structure helps everyone invest and trade better

Today’s stock markets are fast and complicated. But the good news is that there are lots of rules designed to make it look simple and protect investors.

That’s not to say they are perfect. There are ongoing debates about things like odd lots and tick sizes, retail trading, short selling rules – as well as competing ideas on the optimal way to allocate the economics of price setting and trading.

Overall though, our market structure helps make U.S. markets some of the cheapest and most liquid to trade in. And that is even good for issuers.