The 2023 Intern’s Guide to ETFs

This summer, we’ve refreshed our annual intern’s guides for markets and trading. Today we conclude our series with a look at another important part of the stock market ecosystem: Exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

ETFs are one of the most successful financial innovations of the last 30 years. Since their launch (in Canada) in 1990, ETFs have proliferated, and their assets have grown around the world. According to ETFGI, in the U.S., there are now over 3,000 ETFs (right axis, open circles) with assets totaling almost $7.5 trillion (left axis, bars).

Chart 1: ETF asset growth from 2003 to June 2023

What is an ETF?

Almost all ETFs are legally structured and managed as a mutual fund, following the rules of the 1940 Act. But they are also allowed by SEC rules to trade all day on a stock market like a stock.

So, in short, an ETF is both a mutual fund and a stock!

Like other mutual funds, an ETF is professionally managed and holds a diversified portfolio of stocks. Many (but not all) are also index funds, which means their portfolio managers hold almost all stocks in the index but do very little trading.

However, unlike mutual funds, investors who want to buy the ETF do so by trading in the stock market. So, each ETF also has a stock ticker with bids and offers and trades (just like other stocks).

So, a key difference between mutual funds and ETFs is when and how an investor buys the fund:

- Mutual funds: Investors send checks to the asset manager, which are invested by the portfolio manager buying or selling stocks for the portfolio. The investors get “units” of the fund at the end-of-day unit price.

- ETFs: Investors buy and sell with each other at any time during the day – often without the underlying stocks needing to be bought or sold.

So, when you see an ETF ticker, remember it represents a managed portfolio of stocks, as shown below for the QQQ’s ETF.

Some of you may have noticed in Chart 1 a small additional category called “ETPs” and wondered what that was.

- ETP stands for exchange-traded product. It is usually used as a more inclusive umbrella term that includes all exchange-traded stocks that allow creations and redemptions, and therefore arbitrage. For the most part: ETPs = ETFs + ETNs.

- ETN stands for exchange-traded note. ETNs are mostly bank-issued notes with total return swaps into whatever asset class is desired. This means they carry some credit risks (if the bank defaults on debts), but also often means they track their index perfectly. ETNs are often used for commodity exposures (like SLVO, with exposure to Silver).

There are other ways to structure ETPs too. Some hold cash and futures, often to track commodities (like PDBC). These are generally regulated under the 1933 Securities Act, which regulates new security issuance, but not how investments within them are managed.

Today, to keep things simple for the rest of this post, we’ll use the term ETF.

Chart 2: An ETF like the QQQ is a fund that holds the top 100 non-financial stocks on the Nasdaq exchange, in the same weights as the Nasdaq-100 Index® (asset weights as of July 17, 2023)

ETFs evolution: More choice and more active portfolios for investors

ETFs have also matured to offer investors exposure to almost all asset classes, countries, investment styles and market caps.

Early ETFs were exclusively index funds. SPY, the S&P 500 index ETF, was the first to launch in the U.S. It was followed by Select Sector funds like XLE (Energy) and XLK (Technology), which also follow S&P indexes. In the 1990s, there were also tradable country index funds run by banks that later became some of the earliest iShares country funds.

However, over time, the SEC has closed the gap between classic end-of-day active funds (like mutual funds and closed-end funds) and the early index-based ETFs, allowing more active stock selection with easy arbitrage mechanisms.

An even more recent change was to allow active transparent ETFs and active semi-transparent portfolios, a significant development especially given how important it is to investors for an ETF price to be very close to its NAV value. Having less clarity about what stocks an ETF holds does make arbitrage less certain, but the market worked out a way to do this so market makers can still set tight spreads without incurring losses from mispriced quotes.

Chart 3: Evolution of different ETFs, as the SEC closed the gap between index ETFs and active mutual funds

These days many ETFs are not market-cap weighted; some are actively picking stocks, and others mirror the portfolios of established active mutual funds.

Some of the newest ETFs also offer active stock selection and an easy way to invest in some popular themes.

What is net asset value?

Net asset value (NAV) is the value of the ETF portfolio per ETF share. It is relatively simple to calculate the value of many ETF portfolios using the live prices coming from the market for each underlying stock. Using that, you can calculate the fund’s portfolio value, then dividing that by the number of outstanding ETF shares gives a “net asset value” for each ETF share trading at the same time.

You could think of it as the price you should pay for the ETF, except that’s not always true!

That’s usually because the stocks in the portfolio are not trading at the exact same time as the ETF. In those instances, the portfolio includes some old (or “stale”) prices. In some cases, the time delay can be large, and intraday NAVs are just a guide to the ETF’s current value. For example:

- Chinese stocks in an ETF listed in the U.S.: The Chinese market is closed when the U.S. ETF ticker starts trading, and the U.S. market closes before all the underlying stocks open for the next day. What you will see is that the U.S. ETF will “price in” new news that has happened since the Chinese market closed.

- Bond ETFs: Bond markets publish no public quotes (or “tapes” of live historic trades) for the underlying bond markets, making it impossible to accurately value the underlying bond portfolio during the day (or sometimes for days).

How do ETFs track their portfolio?

Even when those NAV timing differences are large, it can help to look at how the ETFs track their underlying portfolios over longer periods.

The data mostly shows that ETF portfolio managers are very good at replicating their target index. For example, when we look at the performance of the QQQ ETF versus the Nasdaq-100 Index® (its benchmark), we see it completely overlaps for a period of more than a decade.

Chart 4: ETFs track target portfolios very well

How much do ETFs trade?

As a group, ETFs trade over $185 billion every day.

That is more than double what the whole European stock market trades each day. However, that’s still not as much as the underlying stock market, which trades around $385 billion each day, or the even more liquid U.S. futures markets, which trade around $660 billion each day.

Although we highlight that futures trading is concentrated in the single S&P 500 exposure, so ETFs allow for a much greater variety of hedges and single trade exposure.

Chart 5: ETF trading and creations versus stock and futures trading

Some ETFs trade a lot. Often without much impact on the underlying stocks – something the relatively small value of creations and redemptions seems to confirm.

That’s possible when one investor wants to buy the ETF from another ETF seller without any liquidity provider or arbitrageur being needed.

It’s also why, especially for liquid ETFs, the spread of the ETF is a fraction of the spread on the underlying stocks. That makes trading ETFs often cheaper than trading the underlying basket of stocks, as:

- The spreads on ETFs are often smaller and cheaper to cross.

- Liquidity on the ETF, which represents a portfolio of stocks, is usually deeper than for any single stock.

Chart 6: Many ETFs trade with spreads much cheaper than the underlying portfolio

Other ETFs trade very little. Despite that, in a recent study, we found that many thinly traded ETFs have tight ETF spreads with frequent quote changes to reflect new portfolio valuations, even though they had few (or sometimes no) trades. That’s a sign that the ETF was never mispriced enough to trigger even an arbitrage trade, and market makers are competitively pricing the ETF, ready for any trade to occur.

Who trades ETFs?

So, who does the most ETF trading?

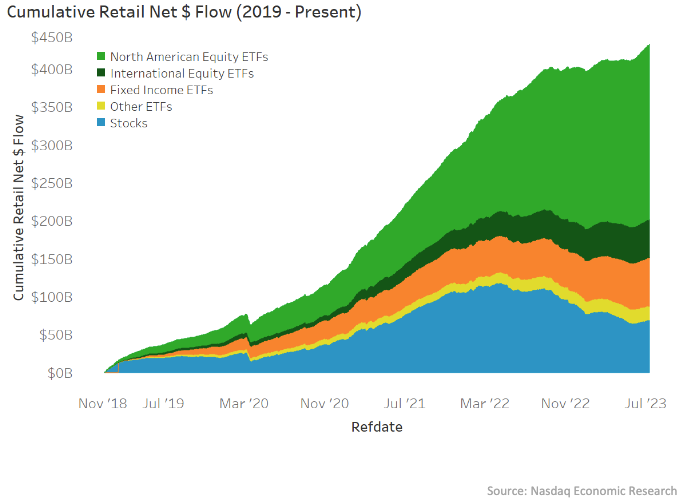

We know from recent research that retail investors are large ETF buyers, with around 70% of their net buying going into ETFs.

Chart 7: Retail love ETFs; data suggest their net inflow has been about $341 billion since 2019

However, the same research shows that retail contributes to less than 5% of all trading each day in ETFs.

We also don’t see many ETFs in mutual fund 13F holdings, indicating that mutual funds are not large traders of ETFs either.

That means ETFs are likely heavily traded by hedge funds, banks and market makers – that’s a testament to their low trading costs, providing effective hedging of more customized exposures than futures. It is also supported by the fact that the 100 most liquid ETFs make up 81.5% of all trading, despite being just 3% of all ETFs (larger circles are high and right in Chart 8).

Chart 8: Some ETFs are extremely liquid; others are used more selectively

What do ETFs trade?

But remember, just because ETFs are U.S.-listed stocks doesn’t mean investors are buying U.S. stocks when they trade ETFs. Data from FactSet on underlying asset exposures shows that many ETFs have no U.S. stock exposure at all. For example, the blue and orange circles in the chart above show ETFs that provide investors with access to bonds, commodities and overseas stocks.

In fact:

- Over $1.5 trillion of the total ETF assets offer exposure to international stocks.

- Over $1.4 trillion is actually invested in bond portfolios.

Chart 9: ETFs give investors exposure to a variety of asset classes, regions, styles and sectors – in one trade; bond ETFs and overseas stocks each account for over $1.4 trillion of the assets in ETFs

What keeps ETFs tracking NAV: Arbitrage

We showed above how closely the ETF price usually tracks its benchmark index. That’s because of two key features:

- Portfolio managers are good at tracking the underlying index, making sure NAV replicates the index returns.

- Arbitrageurs and market makers very efficiently keep ETFs accurately priced.

One important feature that keeps the ETF and the underlying asset in sync is the ability to arbitrage, combined with the creation and redemption feature.

With futures and options, market makers know that at expiry, their long and short positions will collapse, and profits will be locked in. However, that requires arbitrageurs to hold (sometimes large) positions for weeks or even months. That adds to the financing costs and risks while waiting for expiry, which will be factored into futures prices. It can also result in persistent premiums or discounts.

All ETFs have a unique mechanism that allows an arbitrageur to lock in profits and reduce their positions any night they choose. It’s known as the creation and redemption mechanism.

But before a market maker builds a hedged position in stocks and ETFs, the ETF has to trade “rich” or “cheap” versus the underlying stock baskets.

In reality, NAV represents the last trade price for the portfolio. But arbitrageurs care about the bid NAV and offer NAV. They then compare the cost of trading the portfolio with the cost of trading the ETF (as we show in Chart 10).

Chart 10: How arbitrageurs look at ETF valuation

For arbitrage to happen, it needs to be profitable. Arbitrageurs will need to cross both spreads to lock in each side of their trade and secure their profits instantly. That means:

- Creation arbitrage (ETF is rich): When the ETF bid is higher than all the stocks’ offers: Selling the ETF at the bid + buying all the stocks at their offers = profits

- Redemption arbitrage (ETF is cheap): When the ETF offer is lower than all the stocks’ bids: Buying the ETF at the offers + Selling all the stocks at their bids = profits (Chart 11 below)

Chart 11: Arbitrage is triggered when both spreads can be crossed profitably

Once the redemption arbitrage trade above is completed, the arbitrager will be long the ETF and short the basket of stocks. Importantly, all this happens without the ETF itself needing to buy or sell stocks in the portfolio.

The arbitrageur will have close to zero net stock exposure and, therefore, market movements won’t change profits. But there are other costs that need to be factored in, from the cost of borrowing shorted stocks to the settlement fees.

How does creation and redemption work?

There is another feature of ETFs that makes arbitrage even cheaper. Creations and redemptions allow arbitrageurs to reduce their long and short positions, reducing carry (financing and stock borrowing) costs.

In short, any Authorized Participant (someone approved by the ETF manager) can send their ETF back to the ETF manager, and in return, the ETF manager will send them all the underlying stocks in the basket, or vice-versa, any night.

If we start from the arbitrage trade in Chart 11, we can show how this works ahead of trades being settled (Chart 12):

Chart 12: ETF redemption mechanism (three steps to net out your hedged positions)

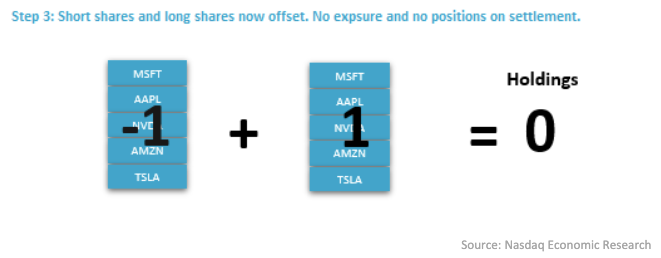

The arbitraged position involves a short stock and a long ETF position (Chart 12, step 1), which is perfectly hedged so additional market movements won’t affect profits.

In a redemption, the arbitrageur gives the long ETF back to the ETF manager, and the ETF manager gives the arbitrageur the underlying shares from the portfolio in return (step 2). The effect of this is shown in the grey box below, where, effectively, the ETF shares are exchanged for real stocks.

That leaves the arbitrageur with long and short stock positions that net to zero, requiring no shares to be delivered on settlement. This reduces the balance sheet costs of arbitrage to zero and eliminates the need to borrow stock to hold the short position.

However, the arbitrageur does have some additional costs they need to account for that range from almost nothing to thousands of dollars:

- ETF managers charge (usually fixed) costs to do creation and redemption, designed to offset settlement and custody costs of the ETF portfolio.

- Arbitrageurs might also need to pay custodians for settling each line of their trades.

Redemptions do represent net outflows from the ETF. However, the selling of stocks occurs during the day, by the arbitrageur, as a result of excess ETF selling. The ETF portfolio manager sees no cashflows and does no trading.

Importantly, in Chart 5, we see that creations and redemptions add to around 4.6% of all ETF trading, and sometimes market-makers will redeem SPY to create VOO if they are doing S&P 500 ETF arbitrage. That’s consistent with a number of studies that find creations and redemptions add to less than 10% of all ETF trading.

Either way, this indicates that only a fraction of ETF trading actually results in stock trading.

What’s the point: ETFs are good for investors, and they know it

ETFs allow investors to buy diversified and professionally managed exposures to all sorts of assets. Data shows they track underlying portfolios extremely well, thanks to good portfolio management, efficient arbitrage and the creation-redemption mechanism.

Spreads are also generally cheap — often cheaper than buying a basket of underlying stocks. Thanks to an efficient network of market makers.

That makes ETFs a cheap and efficient tool for investors that also minimizes stock-specific risks.

In short, ETFs are good for investors, and they know it.