The 2022 Intern’s Guide to Trading

We recently updated our Intern’s Guide to the Market Structure Galaxy, and today we graduate to discussing how trading works.

How to trade stocks?

In our guide to market structure, we talked about how all stocks have a National Best Bid and Offer (NBBO). That is the starting point for how all orders trade.

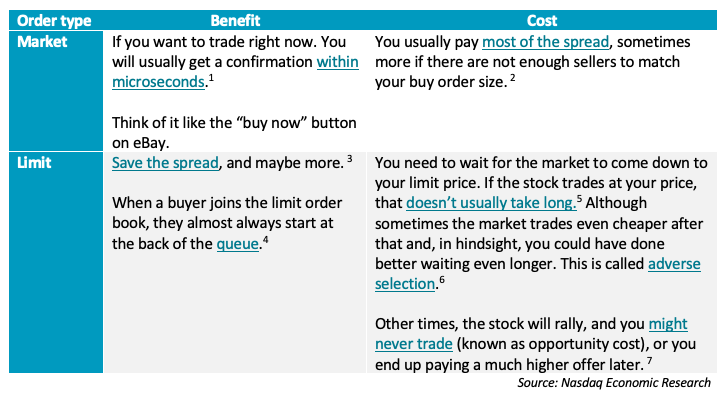

For example, for a buy order, you could trade in two different ways:

1 Time is Relativity: What Physics Has to Say About Market Infrastructure

2 Lit Markets Provide Price Improvement Too

3 What Markouts Are and Why They Don't Always Matter

4 Large Queues are a Small-Cap Problem

5 Are Large Queues a Big Problem?

6 What Markouts Are and Why They Don't Always Matter

7 Routing 101: Identifying the Cost of Routing Decisions

There are other more complicated order types too—from hidden orders at the midpoint between the bid and the offer to others that fade (automatically change their limit to avoid trading) as sellers arrive at the market to avoid adverse selection.

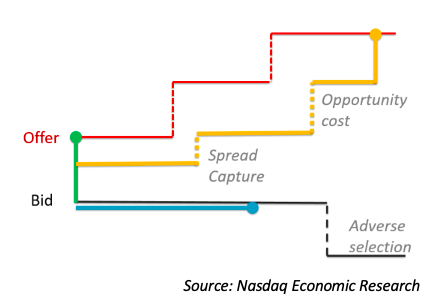

The diagram below shows how market (green), limit (blue) and mid-point (yellow) orders work and the costs of each (spread, adverse selection and opportunity costs).

Chart 1: Traders’ choices and consequences

Who is trading?

There are big differences in how retail and institutional investors trade. For instance, more complicated orders are usually only available to “institutional” traders – mostly because their orders are much larger, take much longer to complete, and benefit more from additional choices.

Chart 2: How much do retail and mutual funds trade?

Data suggests that the average retail trade is small – less than $10,000. That’s important because usually the offer size is much larger than that. That’s important because it means retail market orders should be able to trade instantly and should rarely cost more than the offer price to complete.

But there is another factor that helps retail orders – and that is the fact that retail buying and selling is usually pretty random, something academics call “less informed.” That makes it easier for market makers to capture spread (or avoid adverse selection) trading with just them.

As a consequence, the market has evolved to service retail traders very differently than everyone else, with most orders first sent to Wholesalers (Chart 5), where retail investors frequently get fills at prices better than the NBBO—called price improvement—which occurs in increments as small as 1/100ths of a cent —less than the 1-cent tick that others must use.

Importantly, Reg NMS protects retail investors from bad prices, even when they don’t trade on exchange. NMS Rule 606 tracks all the payments for order flow (PFOF) paid, and NMS Rule 605 keeps track of all the price improvement wholesalers pay, as well as trades executed worse than the NBBO.

Chart 3: Rules to keep track of retail execution quality

If mutual funds are trading?

Mutual funds manage the pooled investments of thousands of retail investors, often professionally researching and picking stocks. That means they often have very large trades to execute in just one stock.

We estimate that mutual and pension funds trade around $90 billion each day, including a lot of cashflows (Chart 2). That adds to around $23 trillion over a year.

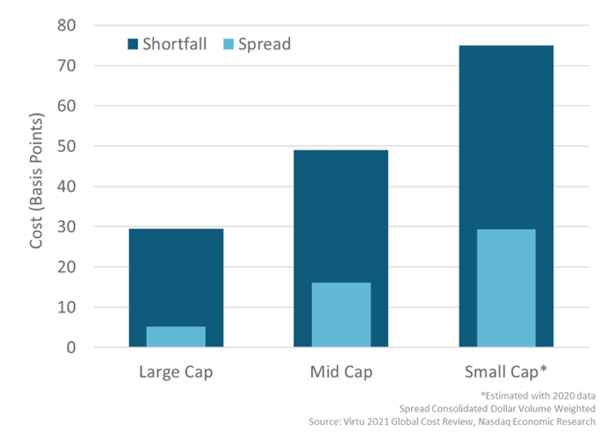

Even though average trade costs are reported at just 0.31%, that adds to around $70 billion each year in trading costs. So, minimizing costs is very important.

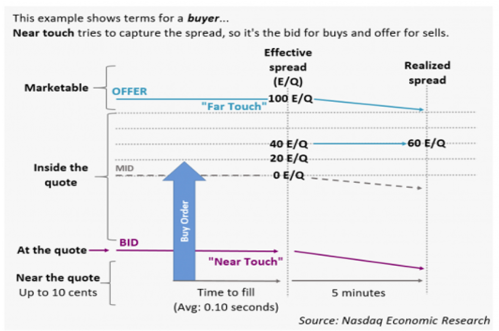

Chart 4: It costs more than spread to finish most institutional orders, and smaller stocks cost more than larger stocks thanks to different levels of liquidity and trading

There are a number of ways institutions minimize trading costs. Three better-known ways are:

- Working orders: As the size of the bid and offer is usually much smaller than the total order size a mutual fund has, brokers will usually “work” orders for mutual funds. That means they split larger “parent” orders up into smaller (child order) pieces. That way, each piece has a smaller impact on supply and demand and, therefore, price.

- Hiding: Others in the market are always looking for signs that a stock will rally or fall (to save themselves money trading). Posting orders in dark pools, or using hidden order types on exchange, allows investors to be in the market without advertising they are there.

- Smartly Routing: Different stocks have wider spreads, longer queues and more depth, and some venues have different trading costs too. An algo and smart router can choose different paths and prices for each child order throughout the day to improve the price and speed of trading.

Where do stocks trade?

Speaking of how routers work, remember that we talked about you can trade most U.S. stocks anywhere. That includes:

- All 16 difference exchanges,

- Over 30 ATSs (dark pools),

- As well as bilaterally with a number of wholesalers or proprietary firms (single dealer platforms or SDPs).

Even for mutual funds, Reg NMS protects investors by ensuring that orders are sent (routed) to other venues if they can’t be executed at prices as good as the public NBBO.

However, as discussed above, the market works very differently for retail and institutional orders. Even the brokers that handle the orders are mostly different, as institutional brokers are experts in building algorithms to work orders, while retail orders are usually handled on a principal basis.

That results in a lot of “internalization” (top 2 circles in Chart 5) before orders are sent to exchanges to trade. In fact, the data suggests around 40% of all trades are executed off-exchange.

Chart 5: Where stocks trade

All the data in these pie charts come from a variety of sources. Exchanges all send their trades to the SIP, with attribution about which exchange did the trade. All of the other trades, though, are considered “off-exchange” and print to the tape anonymously via one of two Trade Reporting Facility (TRFs). However, FINRA reports aggregated flows that break down by trading venue and ticker on a delayed basis, allowing us to show the market share of off-exchange in the charts above too.

Where do the best prices come from?

One of the things we talked about above is the fact that different exchanges have different costs. That’s because they are focused on solving different problems. So-called “inverted exchanges” charge traders looking to capture spread (liquidity providers), which not only creates smaller effective spreads but also puts those orders ahead of long queues at other exchanges that charge spread crossers. However, charging liquidity providers deters limit orders and often results in one-sided markets. Speedbump markets have fewer mark-outs, which make it more profitable for market makers, allowing those exchanges to charge higher fees on their trades.

Tight spreads and a competitive NBBO are important for reducing investors’ costs – even those who trade off-exchange. They also help reduce the costs of capital for issuers. In that sense, tight spreads create important positive “externalities” for lots of other market users – including some who trade very little on exchange.

In studies we’ve done in the past, data shows that it’s hard to attract competitive bids and offers to both sides of all 8000-plus stocks in the U.S. market. However, data clearly shows that exchanges offering rebates to liquidity providers, even though they add to just a fraction of a cent (around 0.3 cents typically), make a big difference to quoting activity. In fact, the tightest spreads, and most real liquidity, almost exclusively come from rebate-paying (so-called maker-taker) markets.

Chart 6: Rebate markets have, by far, the most competitive quotes and also offer the most liquidity

That creates an additional choice for liquidity providers; they can either post inverted and pay to capture more but smaller effective spreads or route to maker-taker exchanges where you capture more than just the spread. Importantly, research suggests the posting fees are almost exactly offset by the additional spread capture on inverted venues – or said another way, rebates make up for the additional costs of waiting.

That’s consistent with other research we have done that shows market makers are very efficient at pricing the cost of more certain liquidity.

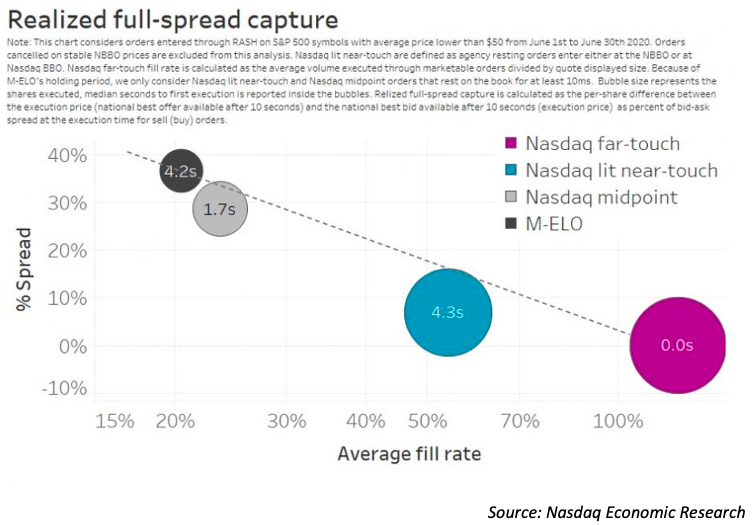

Chart 7: Markets price the cost of waiting, using different order types, very efficiently

How fast should you trade?

Which brings us to an important question: If working orders save money more slowly, but waiting creates opportunity costs, how fast should you trade?

This is the conundrum most traders face:

- Trade faster, and it costs more (market impact).

- Trade slower, and it costs more (opportunity cost or “alpha decay”).

In reality, the optimal trading speed depends a lot on what you and other investors know.

If all investors got the same good information at the same time—say a new product launch or revenue that beats expectations—everyone will want to buy the stock. In that case, trading slower allows others to buy the stock first, pushing the price up, resulting in higher opportunity costs and higher prices later for you.

In that case, you might want to trade fast.

On the other hand, if you have done a lot of unique research that no one else is aware of, trading fast will make your buying more obvious. That, in turn, will make the stock look good to others, like momentum traders, which will also make the stock price rise whether you trade more or not.

In that case, you might want to trade slower.

There is a mathematical way to optimize this problem which we discussed in How Fast Should You Trade? This shows that you need to understand the trading trade-offs:

- Alpha in the trade. For a portfolio manager, alpha is good, as it represents the amount a stock outperforms the market. But trading alpha measures how fast the stock goes up when you want to buy it, even if you don’t trade – so it’s an opportunity cost.

- Trade Size reflects how much your order changes the normal supply and demand.

- Liquidity in the stock determines the minimum time a trade size should take to finish. Smaller cap stocks typically have less liquidity, which limits how large trade in those stocks can be.

- Spread costs add up. Generally, the wider the spread, the more expensive a trade will be (chart 4). That’s because investors typically need to cross more spreads than they can capture.

Once you know all this, you can estimate how trading costs, opportunity costs and risk change over time and minimize your trading costs by weighing the alpha (opportunity costs) against the market impact (cost) of trading faster.

Chart 8: Optimal speed to trade-off impact and opportunity cost can be mathematically determined

People trade at different speeds throughout the day

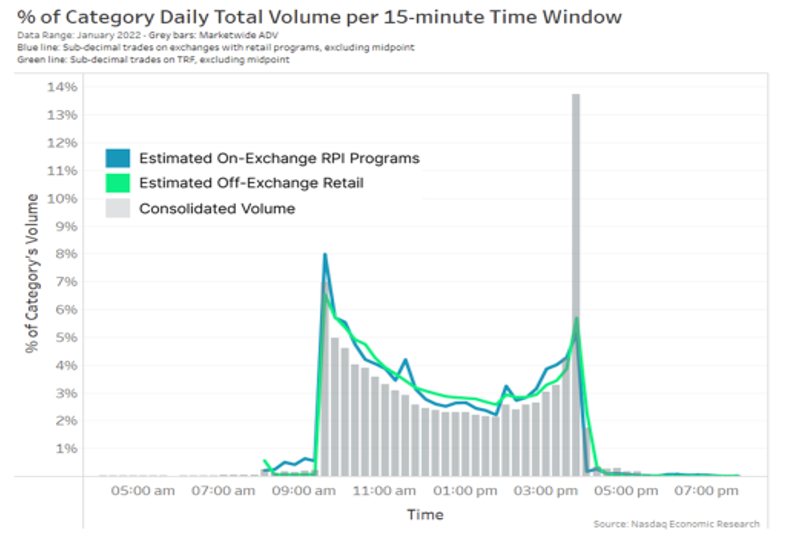

Complicating the problem above is the fact that there is almost always more trading in the morning and afternoon – and less around lunchtime. It’s known as a VWAP curve, or smile.

Other things also change during the day – spreads and price volatility typically fall as the day goes on, making it cheaper to trade with all the liquidity at the end of the day – provided the stock hasn’t already moved on you.

The close is usually the most liquid part of the day. The open and close also work differently to trading during the day. Rather than a bid and an offer creating spread costs, the open and close are auctions, where buyers and sellers add orders, and the “clearing” price is found – where supply equals demand – literally a single price where buy shares equal sell shares.

Chart 9: Trading speeds change over the day

On specific days in the year, when index funds all need to trade, or futures or options expire, closes are even larger. One of them, usually the biggest close of the year, happens tomorrow night.

Don’t stress — computers do most of the trading for investors

Although this all sounds complicated, the reality is that computers (trading algorithms and market maker models) do most of the trading these days, and they can be optimized with data and programmed to fix much of the complexity that human traders face. Some likely even incorporate machine learning and artificial intelligence.

It’s also important to remember that most of the market is also interconnected and automated. The SIP and NMS rules require it.

So, the biggest input required from investors is to decide what stocks they want to buy, tell the algorithm how fast they need to trade, and sit back and watch as fills come in.