Odd Facts About Odd Lots

We’ve talked before about how odd lots are increasing and often provide the best quote in stocks. It was the basis for our own proposals on intelligent ticks as well as some of the SEC’s new NMS II rules last year.

It’s mostly the Securities Information Processors (SIPs) that discern between round and odd lots, only including round lot quotes into the public NBBO. Although, since December 2013, the SIPs have reported all odd lot trades. Exchange matching engines usually don’t treat odd lots any differently. Queue priority is unaffected, and odd lots will fill on a spread crossing order, even if that incoming order is a round lot, often giving those incoming orders price improvement.

Mathematically, that also means any odd-lot trade should leave an odd (or mixed) lot residual quote. That odd residual should, in turn, cascade across future trades, even if new orders are round lots. But we see that doesn’t happen.

So, why isn’t the market full of odd and partial lots?

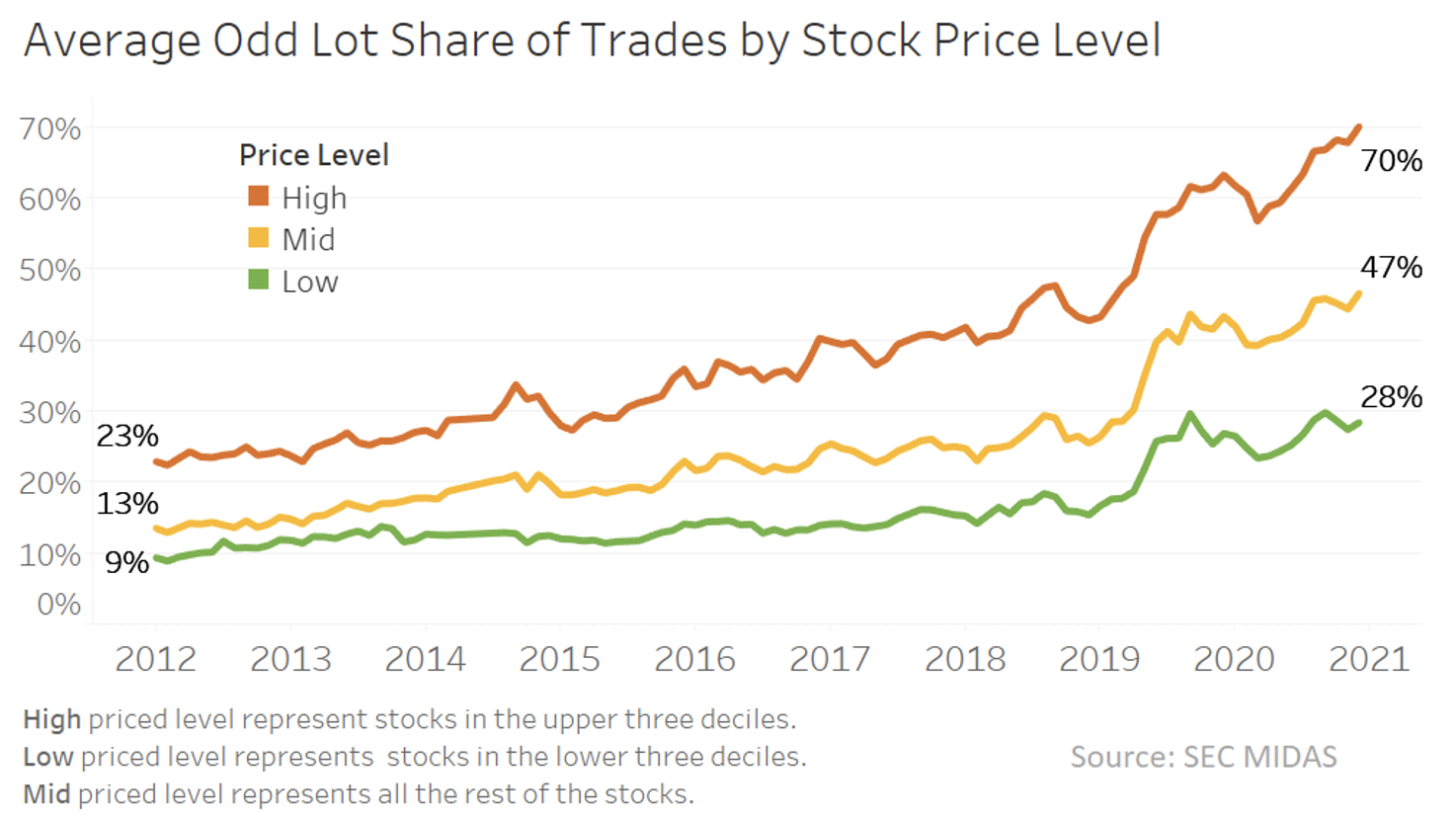

Odd lot trades have been increasing across all stock prices

Data show that as automated markets have become increasingly sophisticated and efficient, odd lots are increasing. At the same time, share prices have also been climbing due to a reduction in stock splits. It seems both are contributing to the increase in odd lot trading. We see that:

- The proportion of all trades that are odd-lot trades has increased for all stock price groups in MIDAS, with odd lot levels roughly tripling over the past nine years across all price levels.

- High-priced stocks have always traded more odd lots, and odd lots have increased to 70% of all trades in those stocks.

That makes sense considering high-priced stocks require much larger trades to post a round lot. For example, a $500 stock requires a $50,000 order to make a round lot. That’s well above the average trade value of closer to $10,000. It’s also a disproportionately large amount of money to have at risk of adverse selection for a market maker, creating a round lot constraint on spreads in those stocks.

The trend makes you wonder whether some algorithms even care about round lot conventions anymore. Exchanges usually treat odd lots and round lots equally, retaining their price, time and queue priority (even if the SIP doesn’t publish them).

Chart 1: Odd lot proportion of trades has increased over time, especially for high-priced stocks

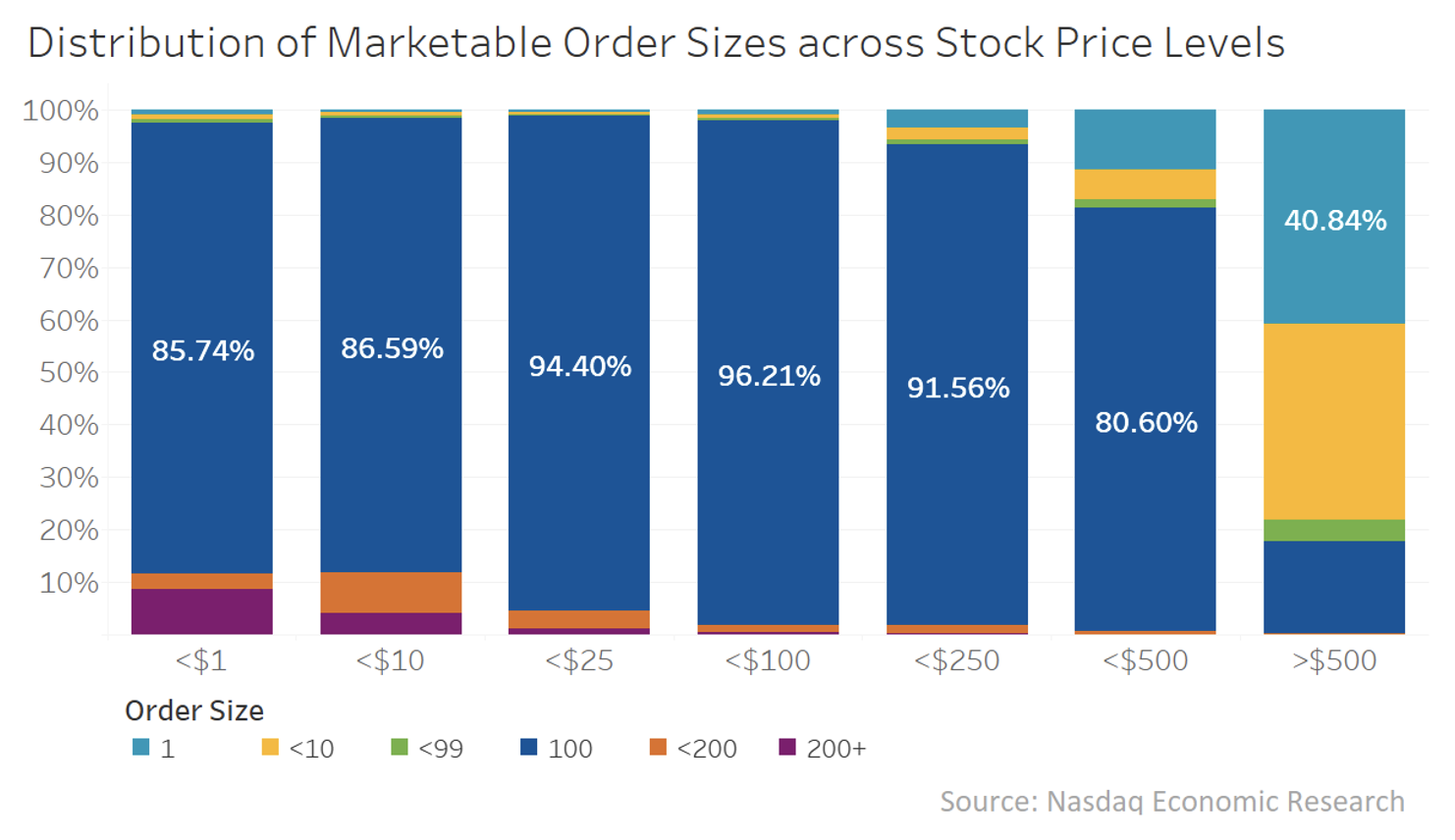

Round lot orders are still more common

Despite the increase in odd lot trades, we see is that many routers and algos still prefer to send round-lot orders. Lots of 100 shares are still the most common size, all the way up to stocks priced around $500 per share. However, above that stock price, the market clearly starts to trade in smaller sizes with one-share orders making up over 40% of all orders (by count, Chart 2).

For low-priced stocks, there are usually more mixed lot (between 101 and 199 shares) than 200+ share orders, at least until you get to stocks below $1 (Chart 2 below).

Chart 2: Nasdaq data show odd lot orders increase above $250 stock price

Single-share trades are still very common

It also interesting to see that single-share trades are as common as they are. The single share phenomenon is something academics have studied for years, and it is often attributed to sophisticated investors.

However, the recent growth of fractional share trading seems to indicate it could be a popular retail trading quantity also. Especially when you realize that FINRA requires all fractional share trades to be rounded up when reported to the tape (see FAQ 101.14 and 101.15). In fact, since November 2019, when fractional share trading was first introduced, the proportion of one-share trades reported to the Trade Reporting Facility (TRF) has increased from 1% of all trades to around 5% of all trades.

Chart 3: One-share orders have been increasing on the TRF

Why doesn’t the one odd lot trade result in more odd lots

Mathematically, even if the rest of the market trades in round lots, just one odd-lot order can (and should) cause odd lots on the majority of subsequent trades. The example order book in Chart 4 shows a single odd lot taker (66 shares) causes six out of eight trades (75%) to be odd lots, even though all other provider and taker orders are round lots.

Chart 4: One odd-lot order should cause a chain of odd-lot trades

But what we find is that trades remain round lots much more than expected. Market-wide, around 50% of all trades are round lots.

In addition, because round-lot trades are usually larger than odd-lot trades, they also make up a much higher proportion of the volume traded, with less than 30% of volumes (shares) in the high-priced stocks trading as odd lots (Chart 5), even though (in Chart 1) odd lot trades are 70% of all trades. For low priced stocks the proportion of volumes that are odd lots is even lower.

Chart 5: Odd lot proportion of total liquidity has increased over time, especially for high-priced stocks

Some routers like to keep the market clean

The big question is: Why aren't more residuals and trades in odd lots?

We followed orders through our own market to see what’s going on. What we find is interesting.

Even though some routers don’t care about round lot conventions, other routers like to reset the market back to round lots. In a way, that keeps the market (relatively) round for everyone.

We find a number of different routing behaviors that do this, including:

- Takers take just enough to clear the odd lots out. Often, takers will size take orders to remove a specific odd lot completely.

- Takers clear the level (and cancel). Alternatively, some takers will send IOC (fill-or-kill) style orders that remove all the liquidity at a quote (but not post any residuals). Often, these routes will be oversized versus the quote, just in case the route hits hidden liquidity too, ensuring the odd lots are also filled. But the IOC instruction means that rather than posting residual odd lots and setting a new limit price level, the system cancels the balance of the order.

- Providers also cancel orders, even if they are still at the NBBO.

- Many orphan odd lots are cancelled. Even more likely is a round lot on the touch is traded by an odd lot, creating an odd residual that no longer qualifies for the NBBO. Given that odd residuals are the only shares remaining at that price level (orphaned), it often cancels. That seems to indicate that being at the public SIP NBBO is important, even if the odd-lot order has price priority.

- Odd lots away from NBBO are canceled. If an odd lot remains in the depth of book, but the NBBO improved to a better price, the odd lot is also often canceled.

Chart 6: Reasons why the market naturally cleans up odd lots

The way we created the data for Chart 6 was to follow 15 stocks of different prices for an entire trading day to see what happens when an odd lot is created in our book. Interestingly, around 84% of the time, the odd lot was cleaned up by the next order instruction (be it a sweep or a cancel). About 60% of the time, the odd lot is swept up by takers. The rest of the time, it is canceled by the adder...

The market has its own ways to keep the market round

Although data shows that many routers don’t care for round lot conventions anymore, especially for higher-priced stocks, the market has some natural ways to reset the quote to round lots most of the time.

In short, the market is a little less odd than it looks.

%20Dividend%20History%20%7C%20Nasdaq&_biz_n=0&rnd=570157&cdn_o=a&_biz_z=1742965949539)