NMS II Doesn’t Fix the Odd Lot Problem

Back before the pandemic, lots of traders were looking at the increase in stock prices and their wider spreads and noticed it was causing odd lots to increase. The SIP committee even proposed adding an odd BBO to their feed, although most of the criticisms were around whether the odd BBO would actually matter, given it wasn’t protected or required to be shown to investors.

Just months later, the SEC instead proposed changing round lot sizes. Today we take a look at just how odd the SEC’s solution looks.

What the SEC is (now) proposing

The SEC’s original proposal would have let orders as small as $1,000 in value set the NBBO. Most commentators said that was too low, especially when the average trade is closer to $10,000 and retail orders average around $8,000. Although spreads might have been tight, lots of market orders might have been “traded through” the new shallow best quotes, making it hard to explain fill prices and Rule 605 execution quality metrics to customers.

So, the SEC adjusted its original round lot proposal to just include stocks over $250. That effectively raised the minimum order size required to set the NBBO to between $10,000 and $100,000, depending on the price of each stock (with the exception of BRK.A).

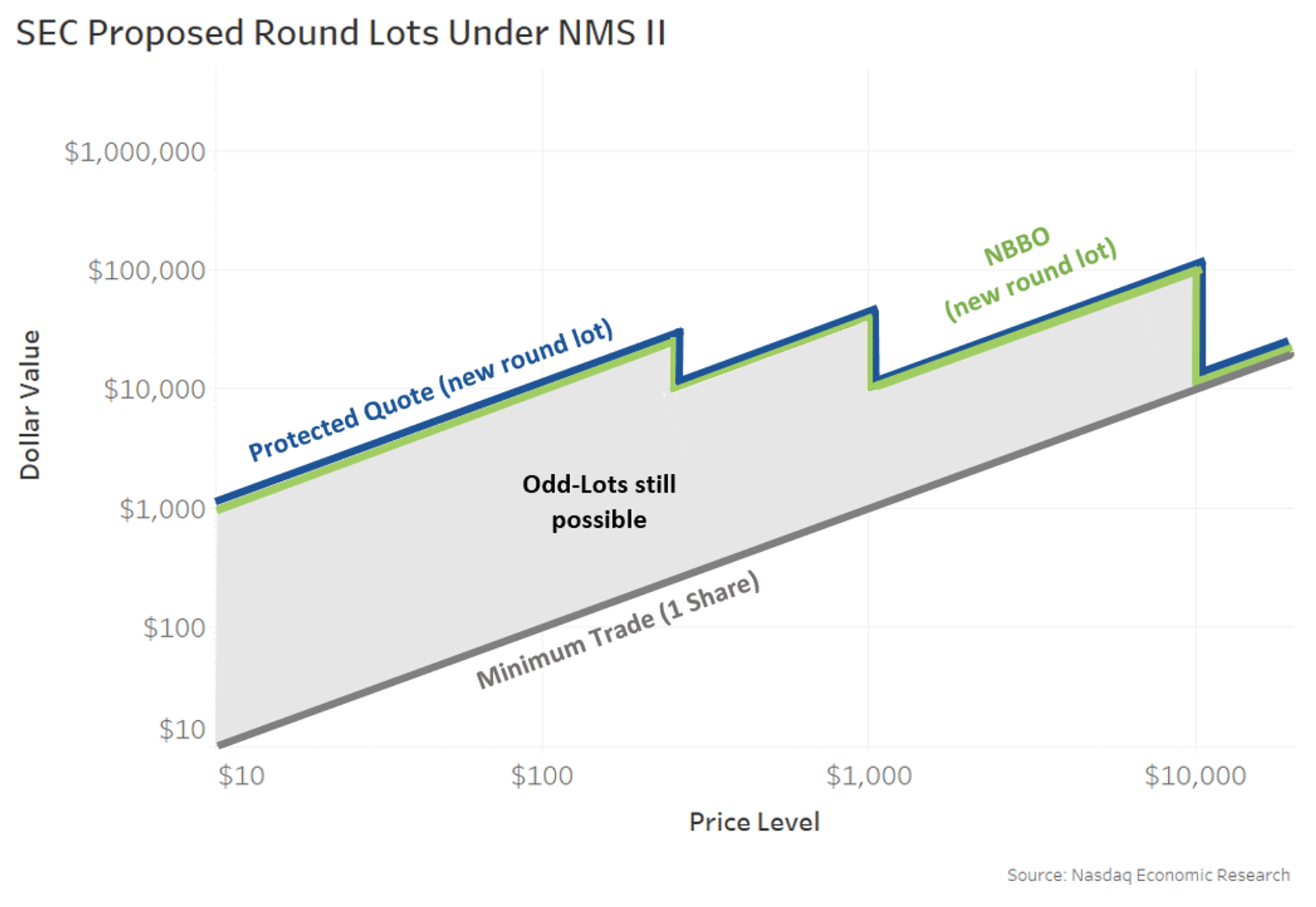

The new round lot sizes will work as we show in Chart 1 below:

- $250.01 to $1,000.00 share price: round lot = 40 shares;

- $1,000.01 to $10,000.00 share price: round lot = 10 shares; and

- Over $10,000.01 share price: round lot = 1 share.

Importantly, the new rules also now protect the smaller NBBO quotes. The original proposal allowed trade throughs of small quotes, potentially defeating the purpose of adding smaller quotes to the SIP.

Chart 1: How the new dynamic round lots change the value required to set the NBBO

How much impact will this really have?

Interestingly, this will impact just 158 stocks.

However, those stocks make up around 24% of all value traded (although, thanks to their high stock prices, just 1.8% of all shares traded). The data also shows that over 80% of the impacted stocks are large-cap stocks (Chart 2).

Chart 2: Count of stocks impacted by the new odd lot rules (color by market cap)

This does not get rid of odd lots inside the NBBO

As the Chart 1 indicates, there is still scope for odd lots to set prices inside the NBBO.

Based on our analysis of existing odd lot quotes for Nasdaq listings, that’s exactly what the data suggests will happen, even allowing for the practice of aggregating odd lots until they form a (new, smaller) round lot for the SIP.

In fact, most Nasdaq-100 stocks over $100 will still have a better odd lot quote than SIP quote more than 50% of the time. That’s down from over 70% now but still high enough to create best-ex questions.

However, we find that the value of odd lot orders that price improve the NBBO falls significantly, especially for very high-priced stocks. For example, today the average value of price improving odd lots in AMZN is nearly $125,000. In the new market, that falls to under $10,000 (circle sizes in Chart 3).

Chart 3: Estimated new percentage of odd lots inside the NBBO

But it should tighten spreads

Buyers and sellers of stocks form fairly consistent supply-and-demand curves (Chart 4). As a price moves away from the mid, the spread increases, as does the quantity available to buy and sell. Plotting this forms a V-shape that studies find has the same slope regardless of how far apart the bids and offers are. We show how this works in Chart 4: 10,000 shares are available five cents away from the mid regardless of whether it is quoted at one price level (bid side) or five different price levels (offer side).

Chart 4: Volume accumulates at the same rate, regardless of what tick increment is used—for the same reason, decreasing the round lot allows a smaller supply (or demand) to form the NBBO

This has implications for the spreads on high-priced stocks as well. Essentially, the spread required to provide $100,000 of liquidity will be higher than the spread required to supply (or demand) $10,000 of liquidity. Therefore, reducing round lot sizes should proportionately reduce spreads.

As Chart 5 shows, high-priced stocks now demand a lot larger supply and demand to qualify for the NBBO (light green bars).

We also know that, especially for high-priced stocks, not everyone wants to trade in the size required to make NBBO. Essentially these stocks become “round lot constrained,” resulting in wider spreads than other similar stocks (U-shape to the orange line).

Given what we know from Chart 4, the expected spreads on $1,000 stocks should tighten 90% as the round lot falls from 100 shares to 10 shares (by 90%) (dotted orange line in Chart 5).

However, our data on Nasdaq-100 stocks suggests the odd lots we currently see combined with the proposed smaller round lot rules might tighten spreads much less (dashed orange line).

Chart 5: Current data suggests spreads won't tighten as much as expected

An odd result

Odd lots in the market are one of the few problems almost everyone seems to (mostly) agree on. Sadly, finding a solution everyone agrees on is what has proven difficult. Retail investors with small orders deserve the most competitive lit prices the market can offer, while institutions need liquidity and spreads that make it worth trading on exchange.

As we found last week, investors already send orders that are smaller than (even) the proposed new round lots. Today’s data suggests odd lots are still going to be a bigger problem than traders would like.

A better solution involves a market where all orders count equally, and the lit quote is as competitive and inclusive as possible, while also ensuring spreads are deep enough to fill most orders.

Sadly, resetting round lots just resizes the problems we already have.