Nasdaq: 50 Years of Market Innovation

This month marks the 50th anniversary of Nasdaq’s launch in 1971.

The story of Nasdaq’s first five decades highlights its impact on trading today. The introduction of computers to markets, and sharing of quote data more widely, led to the automation of trading. With that automation came huge cost savings that, together with the internet, have democratized investing and helped the U.S. market stay the biggest, deepest and most cost-efficient market to list and trade in in the world.

Nasdaq brings computers to the market

Back in 1971, the SEC urged the National Association of Security Dealers (NASD), the regulator of OTC (or ‘Over-the-Counter’) brokers, to automate the market for securities not listed on any exchange.

That represented a shift from the traditional floor-based trading models of exchanges around the world. Historical records show Nasdaq set up one of the first “data centers” for trading, complete with tape drives, monochrome cathode tube screens, sideburns and plaid trousers. Data centers have certainly changed a lot since then.

Exhibit 1: A Nasdaq data center in 1971, the year the company’s electronic exchange began operating

Courtesy of the Museum of American Finance

Bringing quote data to the broader market (1970s)

With most floor-based markets, all investors would see was a ticker tape of historic trades, well after the fact.

The NASD contracted with the Bunker-Ramo Corporation of Trumbull, Connecticut, to build a system in which market makers in OTC stocks could electronically update their bid/ask quotes. That system launched on Feb. 8, 1971, as the National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations (hence the acronym NASDAQ).

Exhibit 2: One of the early Bunker-Ramo computer terminals used to make and see quotes

Source: Nasdaq

A stream of electronic quote history was created and available to many users equally and simultaneously, something that most users of the Securities Information Processor (SIP) now take for granted.

A more equal and competitive marketplace

With floor-based markets, there is a distinct advantage to having a physical presence on the floor, a presence that creates informational and speed advantages.

Nasdaq, of course, has never had a physical floor. What it had instead was a type of “open architecture” platform that electronically connected competing market makers. The competing market maker model created incentives for an ever-increasing level of customer service regarding connectivity, fees, and liquidity provision.

That, in turn, led to a more competitive quote and a more equal trading model, benefiting a wider variety of participants with the same access to markets and tools to trade. This philosophy is still intact today.

Moving toward publicly available depth-of-book data (1980s)

Over the years, Nasdaq’s quotation service was continually enhanced in terms of processing performance and the level of information provided. Over time, more data was shared more easily, for the benefit of a wider range of investors and traders.

The main data innovation in the 1980s was the creation of a real-time “Level 2” data feed. More than simply providing the best bid and offer, Level 2 provided a complete quote montage to subscribers, indicating the quotes of all market makers. This feed was provided via uniform access across all participants. There were no informational advantages to particular traders. Level 2 foreshadowed Nasdaq’s future market data offerings, as well as those from other markets, offerings which today are considered valuable inputs to the trading process for many market participants.

By the mid-1980s, Nasdaq introduced an interface, the Nasdaq Workstation, which could run on standard desktop computers. The system allowed brokers to advertise to and interact with each other, so the montage displays the bids and offers of named market makers, ranked by price. The color scheme shows depth levels away from the national best price (yellow).

Exhibit 3: The quote montage from the Nasdaq Workstation II in the late 1990s, showing depth but still showing prices in fractions of a dollar

Source: Nasdaq Economic Research

Automating executions after the 1987 crash

While quotations were automated, the traditional process of matching trades was initially still done via telephone. The market crash of 1987 revealed drawbacks of the telephone-based system, as many market makers were unable or unwilling to interact verbally.

During the 1980s, Nasdaq responded by providing two electronic trading systems:

- The Small Order Execution System (SOES) automated executions against market maker quotes. After the crash, SOES became mandatory, although with maximum order sizes of 1,000 shares in order to protect market makers from too much adverse selection.

- The SelectNet system allowed for efficient non-telephonic communication between traders with the ability to create locked-in trades—somewhat like email for trading.

Both systems came to contribute to a sizeable fraction of trading on Nasdaq. The SOES system ultimately gained a level of notoriety due to its use by day traders, colloquially branded “SOES Bandits.”

The emergence of all-electronic trading sped up the market and opened the door to much higher trading volume.

Access to public markets for more investors (1990s)

With the advent of the Order Handling Rules of 1997, the Nasdaq network began to include a new type of market center, Electronic Communications Networks (ECNs), which were electronic order books.

The quotes of market makers were combined with the top-of-book quotations from ECNs to provide a complete view of the liquidity available for any given Nasdaq stock. ECNs, like market makers, faced competitive pressure to innovate and improve performance. The Nasdaq world, then, became a hotbed for the development of ever-improving trading technologies.

Listings: The stock market for the next 100 years

The Nasdaq wasn’t just about the automation of trading, though. It was also established as a listing venue for new, growth companies. Along the way, we attracted some of the world’s most innovative and impactful companies.

Intel had its IPO on Nasdaq back in 1971 and was followed by the likes of Apple in 1980 and Microsoft in 1986. Not only was Nasdaq providing technology to markets, but it was also attracting technology companies to its markets. During the 1990s, Nasdaq established its “new economy” brand, running a series of highly effective advertisements with the tagline: “The stock market for the next 100 years.”

Exhibit 4: Some of the early companies to list on Nasdaq

Source: Nasdaq Economic Research

Nasdaq’s tech-heavy orientation was well manifest during the dot.com bubble of the late 1990s. In spite of the resulting pain as the bubble popped, the Nasdaq brand was permanently etched into the financial mindset. To this day, the Nasdaq Composite index—“the Nasdaq”—is referenced countless times every day. The brand has been further extended thanks to the Nasdaq-100 tracking QQQ ETF, one of the earliest and most successful ETFs.

Lower costs drive liquidity and activity (2000s)

You may have noticed that Exhibit 3 shows quotes in fractional prices: sixteenths, eights, and quarters of a dollar. As computerized trading increased, competition to be at the best price increased. ECNs looking to take market share introduced smaller ticks that, in turn, helped start a dramatic reduction in market-wide spreads.

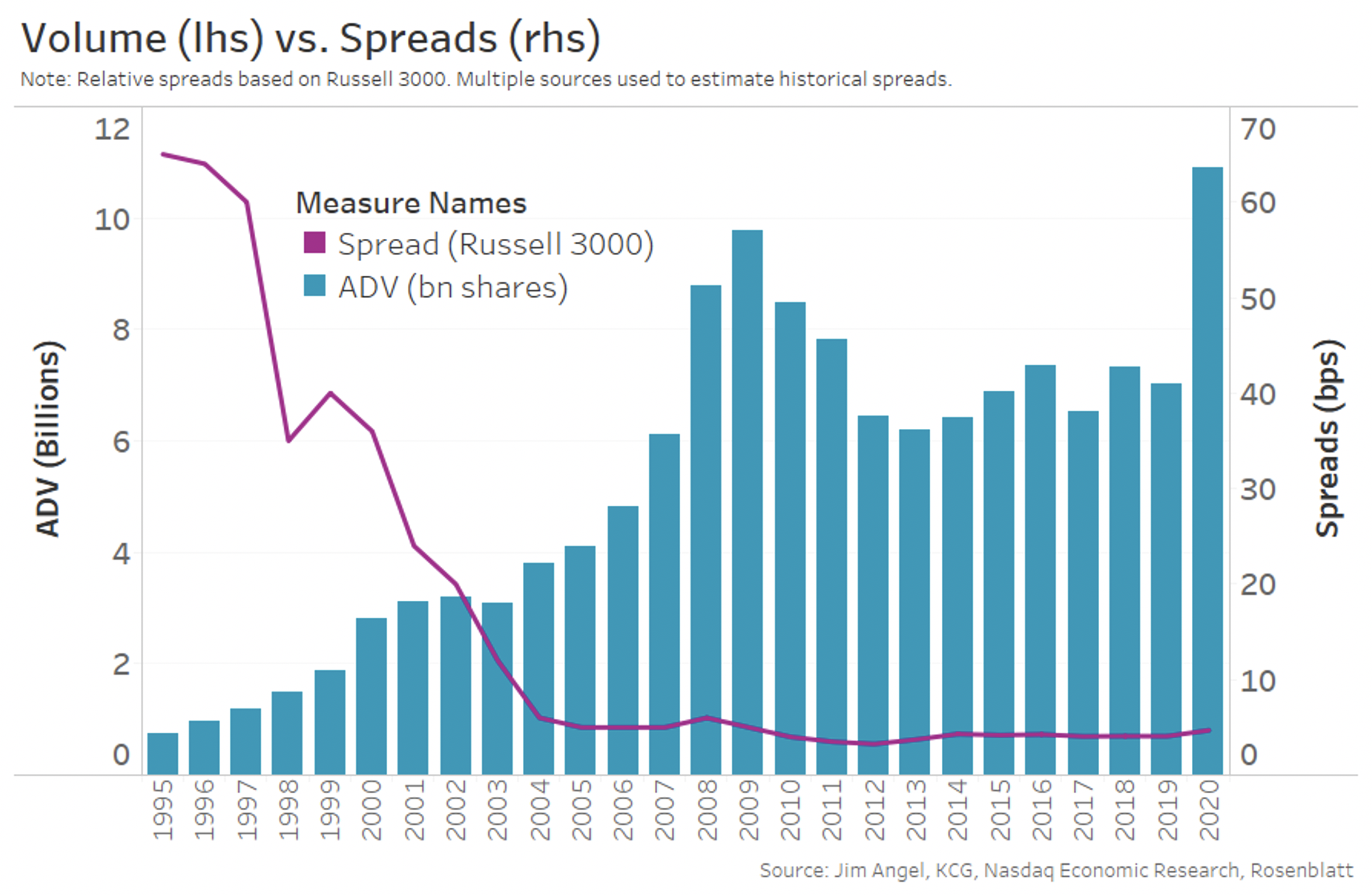

It wasn’t until 2000 that the U.S. market converted to decimal quotes. By 2005, markets had seen spreads decline 90% over just the past ten years. Over the same period, as costs fell, trading activity and liquidity also increased tenfold.

Exhibit 5: The impact of market-wide automation on trading costs and liquidity

By the turn of the century, electronic trading had also expanded to institutional brokers and algorithms. The proportion of trading that leveraged all this new electronic data for working orders also increased, in turn making message traffic grow.

By the early 2000s, Nasdaq determined that the trading technology of INET, one of the new ECNs, would provide a needed replacement for Nasdaq’s own technology. INET was itself the product of the merger of the Instinet ECN, known for its institutional reach, and the Island ECN, known for its extremely low level of processing latency. In 2005, Nasdaq acquired INET, and during the following years, adopted its order book trading technology and data platform. It is this technology and its enhancements that powers Nasdaq trading applications to this day, along with those of many other Nasdaq technology customers.

Nasdaq becomes an exchange for investors that investors can own (2005)

In 2005, Nasdaq converted from an industry-owned organization to become a public company with its own IPO and, with its ticker, NDAQ, listing its own shares on the Nasdaq exchange.

Nasdaq was now an exchange for investors owned by investors and returning profits to investors.

Many U.S. households have since benefited from Nasdaq’s central role in the automation, growth and innovation of markets worldwide.

Reg NMS codifies the electronically interlinked U.S. market structure (2007)

As it became clearer that the markets were becoming more and more electronic, the SEC moved to modernize old trading regulations with the introduction of Reg NMS. Reg NMS mandated many things we take for granted today: quotes that are publicly available and actionable, prices that can be consolidated in real time to create an NBBO, and an interconnected market that helps investors always trade on markets with the best prices.

With fair access rules, the way Nasdaq market makers had always used the system to “internalize” the trading of customer orders also needed to be separated from the operation of the exchange. Thus was born a new way for brokers to report trades matched off the exchange, via the newly-formed Trade Reporting Facilities (TRFs). With this development, the current market structure for U.S. equities was largely established.

As we look forward, don’t forget to look back

Computers have created a revolution in financial markets across the world. The most electronic markets are also the most transparent. They also offer the most uniform information and access to all kinds of investors.

The ability to create and send orders, execute trades, book and settle fills electronically has replaced costly manual processes. Productivity increased, errors decreased, and administrative and trading costs came down.

It’s ironic to think that less than 50 years ago, top-of-book quotes that all investors could see was just an idea, and depth-of-book data would only be made widely available purchase by all traders in the 1990s.

Nowadays, retail investors have the same access to equity prices on their TV and can use their phones to trade stocks in the very same markets as professionals. Automation has reduced costs and improved access to markets for all investors. Data has helped democratize trading.

But let’s not forget that even today, only exchanges are willing to share data equally with the whole market.

It’s easy to take for granted all the transparency and efficiency that automation has created. But, as we look back at the past 50 years, we see that many of the benefits that equity markets have over other asset classes are due, in large part, to the way Nasdaq helped to automate and democratize trading.

Jeff Smith, Associate Vice President of Economic and Statistical Research at Nasdaq, contributed to this article.