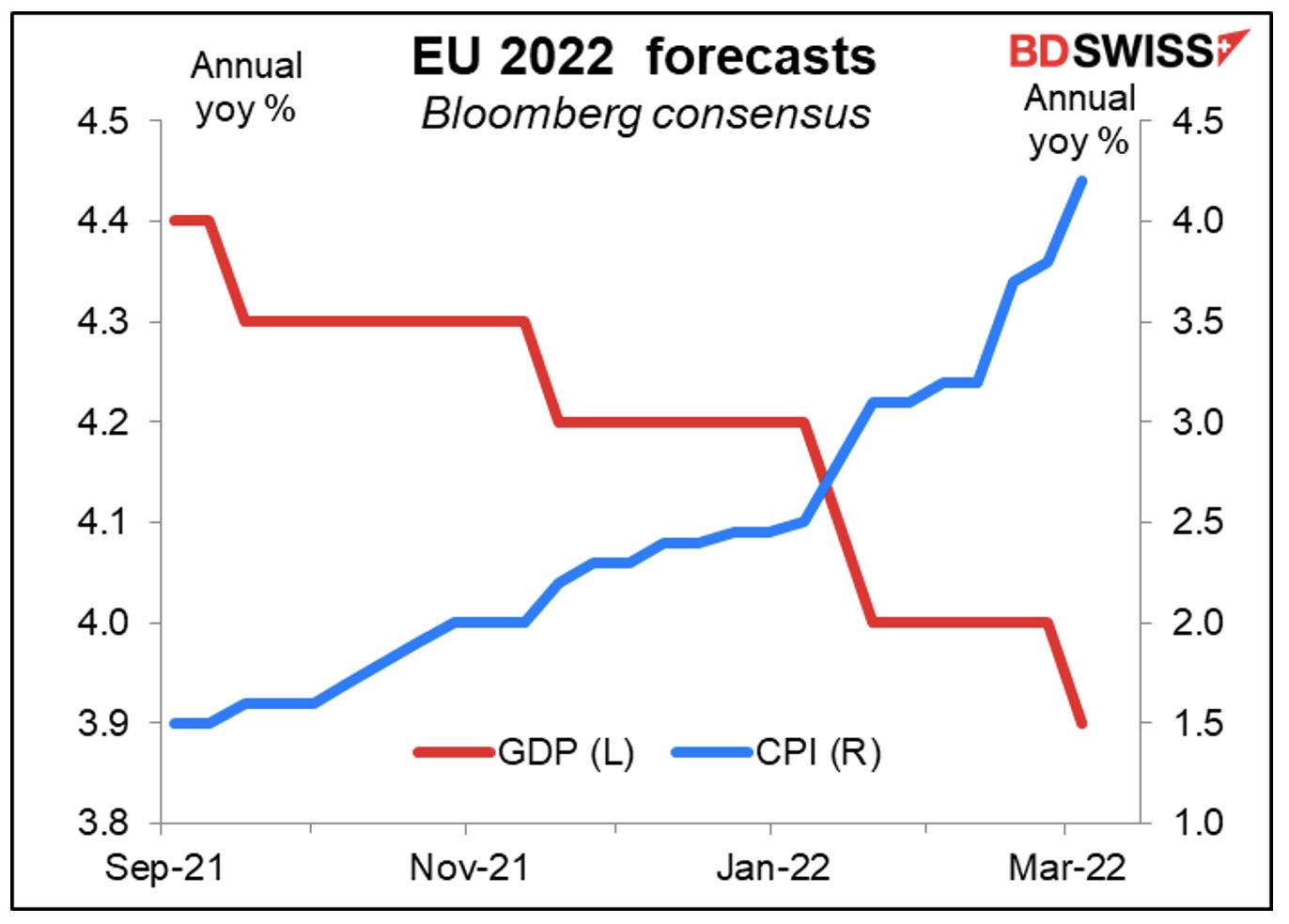

This will be a difficult meeting for the European Central Bank (ECB). At their last meeting just six weeks ago, they outlined a path to policy normalization in the face of higher-than-expected inflation. Now they are facing the prospect of even higher inflation and above-target inflation expectations against the background of an economic shock that’s bound to slow activity if not cause an outright recession.

The big question they will have to address then is, how will the fighting in Ukraine affect the inflation outlook? The impact isn’t clear. On the one hand, surging commodity prices increase the risk of higher inflation lasting longer than anticipated. (Remember that the ECB’s inflation target is headline inflation, not core inflation, so rising energy prices have a direct impact on their thinking.) On the other hand, the increase in uncertainty caused by the fighting is likely to dampen the economy, not to mention the drain on spending caused by higher food & energy prices.

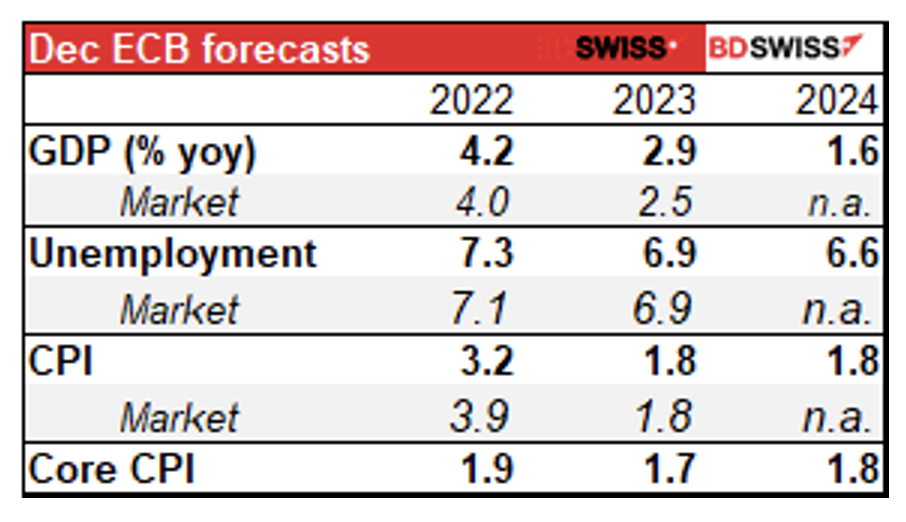

They will get new staff forecasts at this meeting. These forecasts were made using data up to Feb. 15th, before the invasion, so to some degree they’re already out of date. However ECB Chief Economist Lane said in a recent speech that the staff would take into account the most recent data and events in setting the forecasts.

In normal times, if the crucial 2024 forecast for inflation is at the 2% target or above, that would trigger the start of policy normalization.

What they would’ve done if Ukraine hadn’t been invaded

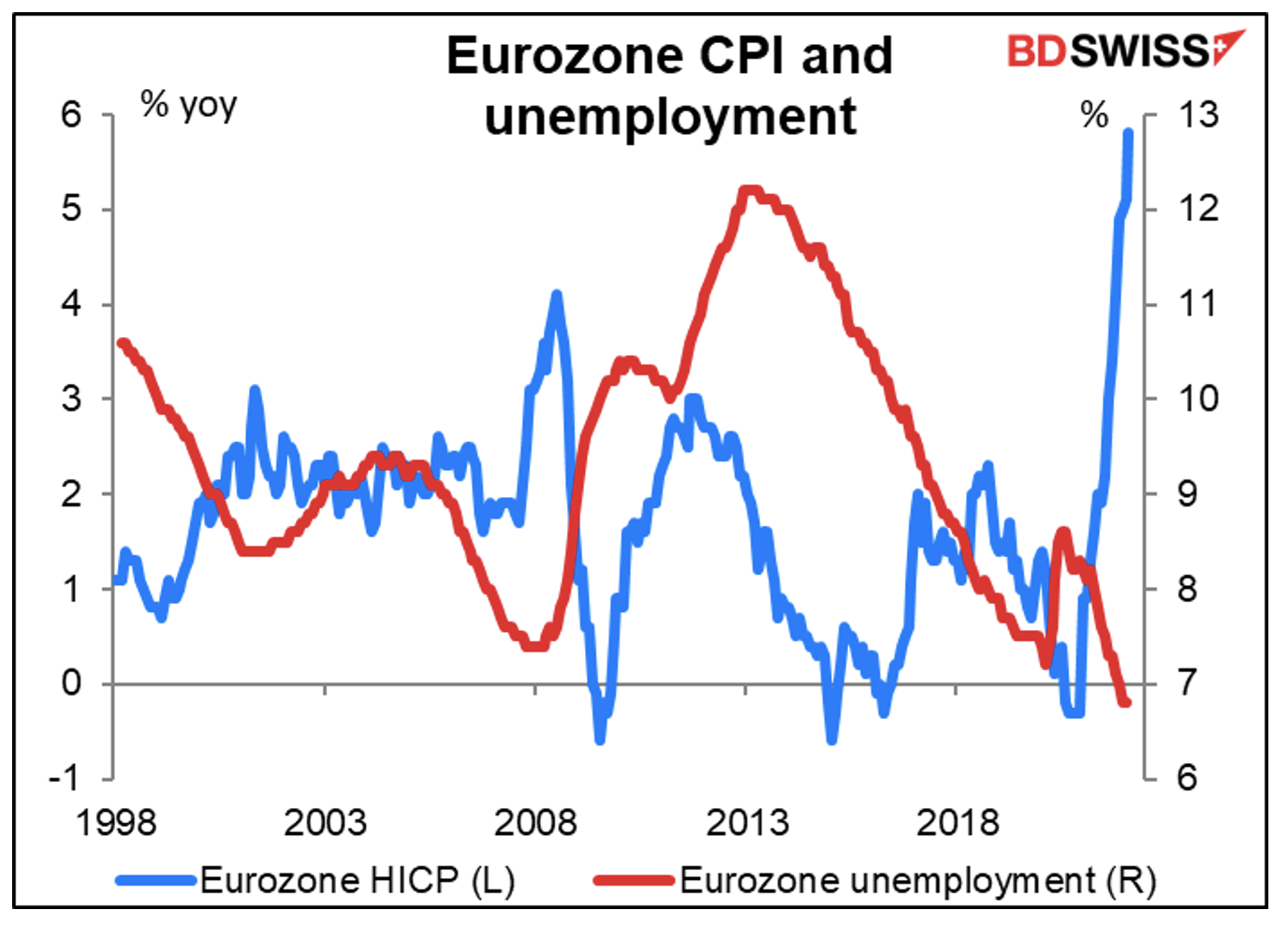

With inflation of 5.8% far above their 2% target and unemployment at a record low (data back to 1998), under normal circumstances they would’ve announced at this meeting that they were ending their EUR 1.85tn Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) on schedule at the end of March and tapering down their Asset Purchase Programme (APP) purchases more rapidly than planned.* This was the plan back in February, when President Lagarde said, “We will stop the Pandemic Emergency Programme net asset purchases in March and then we will look at the net asset purchases under the APP.” They have said they’d be willing to carry on the PEPP purchase “if necessary to counter negative shocks related to the pandemic.” Ukraine has nothing to do with the pandemic, but they might still want to continue them.

“We expect net purchases to end shortly before we start raising the key ECB interest rates,” they said. The other topic that should’ve been on the agenda for this meeting then is how long “shortly before” means.

(*At their Dec 2021 meeting they decided to buy EUR 40bn a month in Q2, EUR 30bn a month in Q3 and EUR 20bn a month from Q4 “for as long as necessary to reinforce the accommodative impact of our policy rates.”)

This time however they are likely to put the normalization process on pause while they wait to see how things develop in Ukraine. ECB Chief Economist Lane noted in his latest speech that they won’t have all the information that they need on March 10th. However, this would just mean policy normalization is delayed, not derailed.

The unique problem of the ECB: 19 bond markets to worry about

The ECB’s policy is far and away the most complicated of the central banks’. That’s because it has two roles: its official responsibility for price stability, which it shares of course with all other central banks, and what might be called market stability. Other central banks only have one government bond market in which they exert their influence, but the ECB has to operate in 19 different government bond markets. It has to ensure the smooth transmission of its policy across all member states and ensure that no country’s bonds get way out of line. Remember the furor when ECB President Lagarde said at her third ECB press conference (March 2020) that “We are not here to close spreads” between government bond markets. “This is not the function or the mission of the ECB.” She quickly learned that she was wrong and that the markets assume this is one of its tasks.

In normalizing policy, the ECB not only has to worry about rate hikes but also what to do about their two bond purchase programs, the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) and the Asset Purchase Programme (APP). The PEPP is an EUR 1.85tn program initiated in March 2020 “to counter the serious risks to the monetary policy transmission mechanism and the outlook for the euro area posed by the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak.” The APP “was initiated in mid-2014 to support the monetary policy transmission mechanism and provide the amount of policy accommodation needed to ensure price stability.”

The big difference between these two programs is that purchases under the PEPP are largely unrestricted. The ECB can buy whatever kinds of bonds, of whatever maturity, and whatever nationality it wants to. The APP purchases however are restricted by nationality: the ECB has to be “guided by the capital key” in making its purchases. The ECB capital key is how much capital each country contributed to the ECB. It’s determined by each country’s share of the population and GDP of the Eurozone as a whole. This measure is different from each country’s share of the Eurozone bond market. This can create problems if (when) a country gets into financial difficulties and needs more help than it is proportionally allowed to receive.

Some ECB members have been talking about new policy instruments to take the place of the PEPP to prevent market fragmentation. They are likely to discuss this at this meeting but not make any decisions yet. They may have to establish what’s being called a new “separation principle” in ECB policy that will allow them to separate the functions of “price stability” from “market stability” or “policy stability.” They want to be able to raise rates if necessary for price stability but to keep the various national bond markets from fragmenting. It’s particularly important now as soaring energy prices will hit countries differently depending on how energy-intensive their economies are. The ECB may well have to invent yet another new policy instrument to deal with the pressures that this new stress causes.

Without such a new instrument, the ECB is likely to continue to stress its “flexibility” and “optionality.”

Will inflation let them wait?

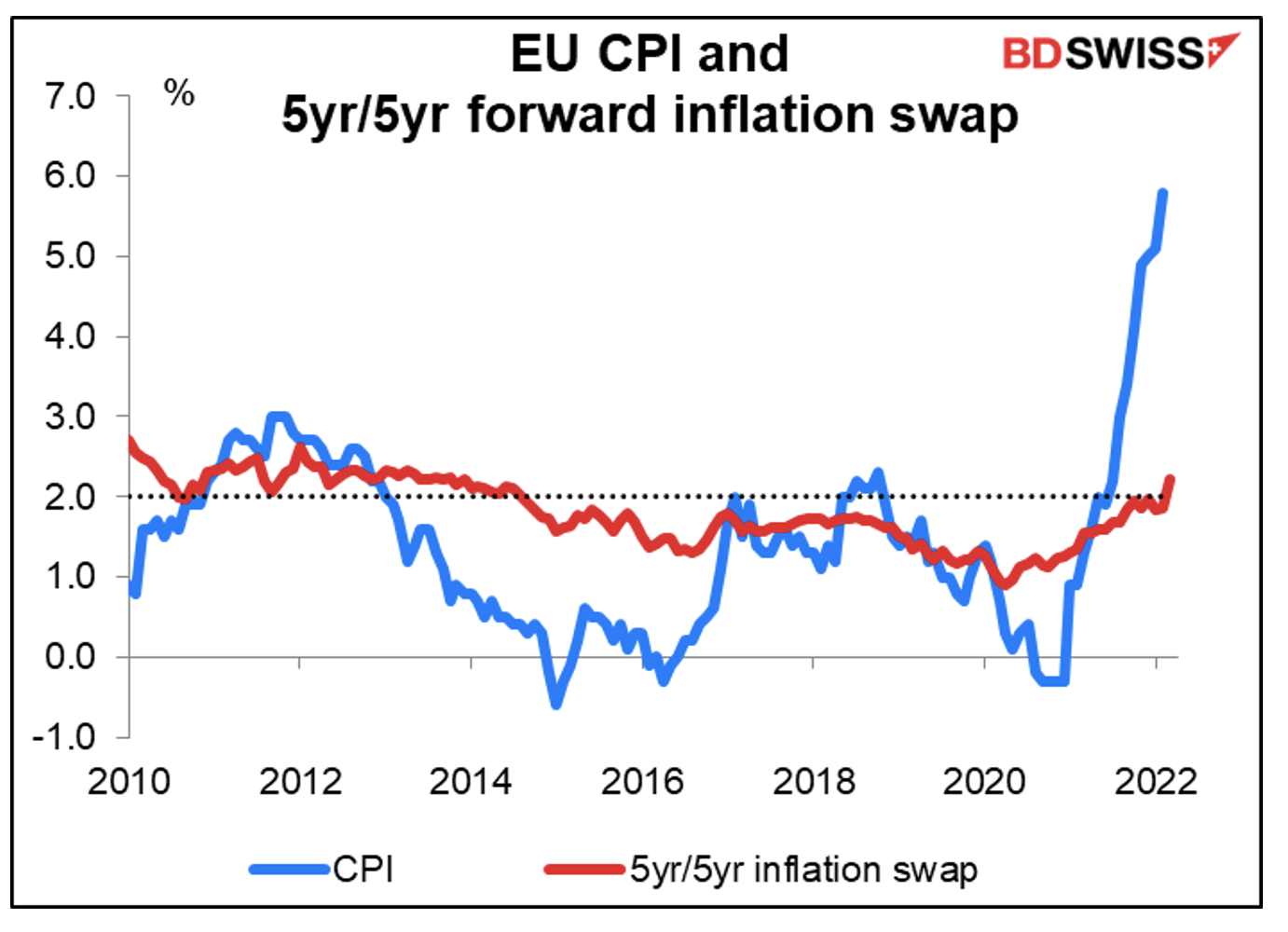

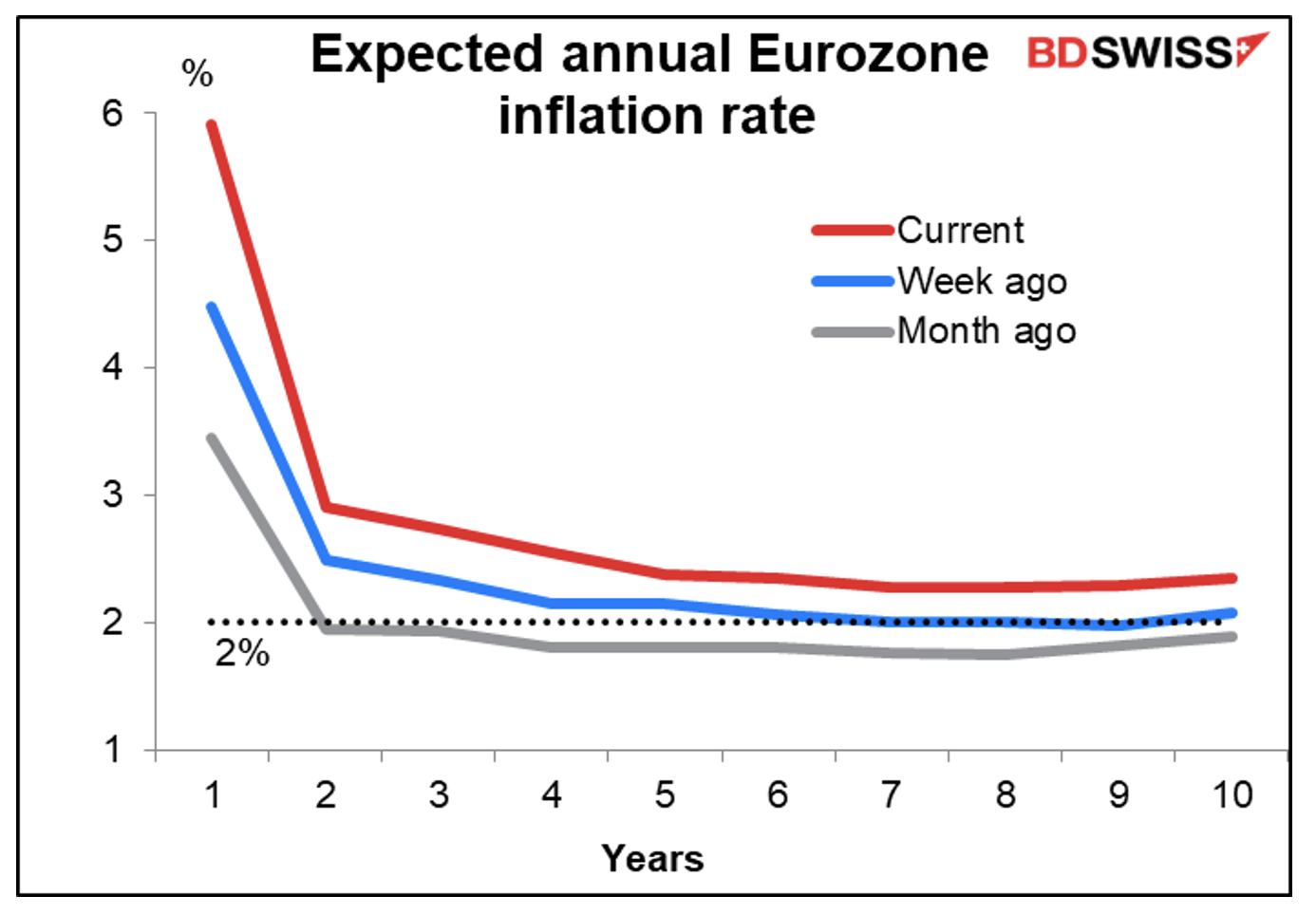

The problem facing the ECB is that not only is EU inflation at 5.8% yoy far above their 2% target, but also inflation expectations are rising too. The 5yr/5yr inflation swap, the ECB’s favorite measure of inflation expectations (expected inflation for the five years starting five years from now) is now at 2.21%, meaning the market doesn’t expect the ECB to be able to get inflation back down to its target.

Even worse, if we use that same methodology to calculate what the market expects for inflation for a year starting two years from now, three years four years, etc. we again don’t find the market expecting inflation to come down to 2% even over the next 10 years. This is a big change even from just a week ago.

Using this methodology by the way the market expects 2024 EU inflation to be 2.91%. If the EU staff were to forecast that, they would almost have to act.

One of the things that keeps central bankers up at night is the fear that inflation expectations might become “unanchored.” That is, if people don’t believe the central bank can keep inflation in check and start to assume higher inflation in the future, they’ll build that into their assumptions and it may become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Labor unions will demand higher wages, thereby causing a wage/price spiral. People will prefer to spend rather than to save, thereby increasing demand now.

Central bankers are therefore desperate to act before this happens. ECB Chief Economist Lane has warned that such expectations may leave the ECB no choice but to act “decisively” to protect the credibility of its inflation targeting, even when the upward pressure on inflation expectations arises from some outside force, such as a disruption to supplies, which is what we’ve seen recently. They could therefore still surprise the market with some tightening measures in order to maintain their credibility in the face of surging inflation.

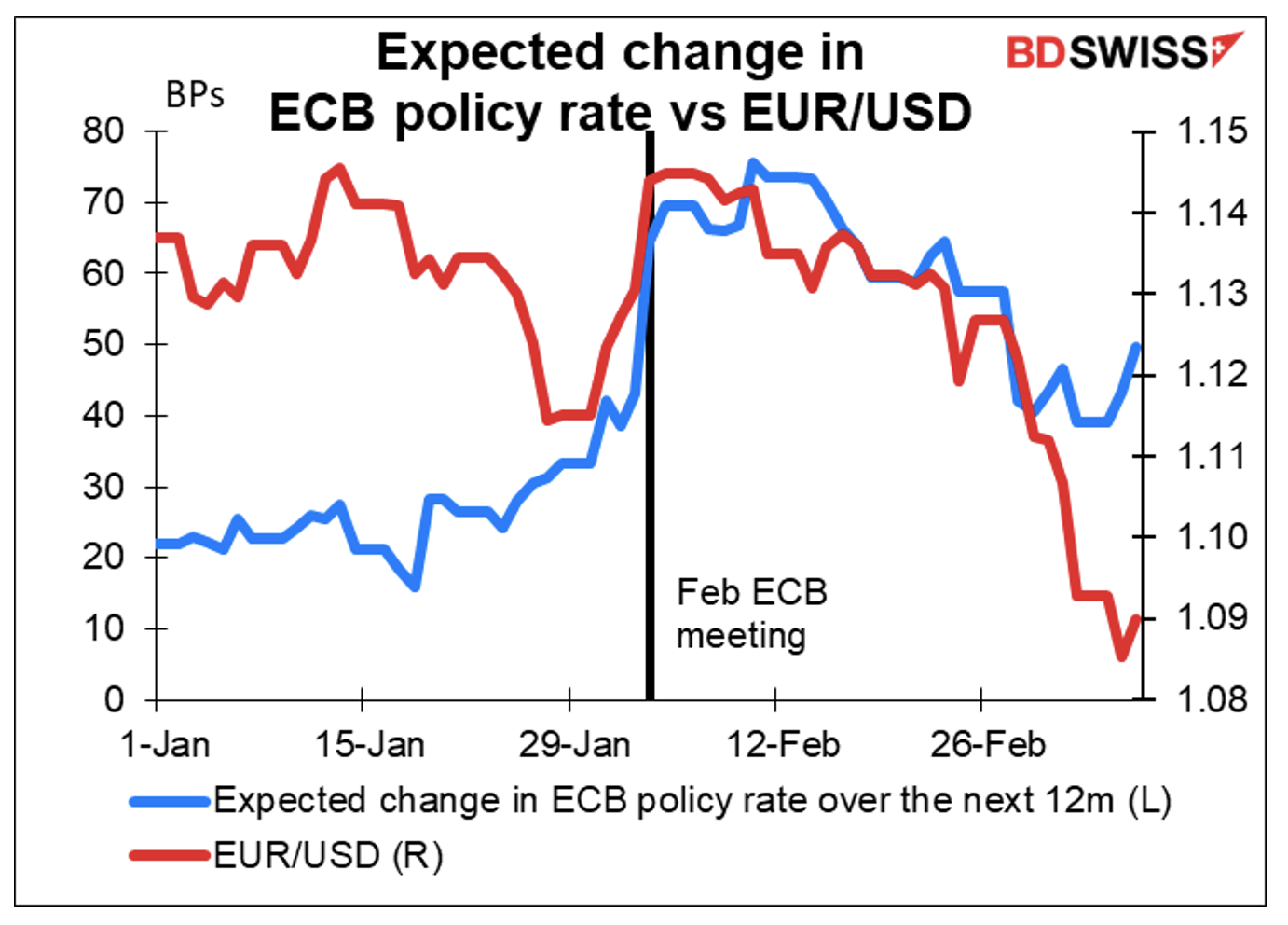

It appears that the market has started to price in that possibility as the expected change in ECB policy rate over the next 12 months has stopped declining and turned up a bit. Hints at this meeting that the ECB will proceed with tightening even in the face of a slowdown could cause EUR to strengthen. On the other hand, an emphasis on caution and uncertainty could cause EUR to weaken further.

The views and opinions expressed herein are the views and opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Nasdaq, Inc.