This past weekend was the eighth anniversary of the famous 2013/14 “taper tantrum.” In light of the fact that last week’s minutes of the April meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) made the first mentions of tapering down the Fed’s monthly bond purchases, it’s worth reviewing the original taper tantrum, event, because we’re likely to see it repeated.

At a Congressional hearing on May 22, 2013, then-Fed Chair Bernanke said in response to a question: “If we see continued improvement, and we have confidence that it is going to be sustained, in the next few meetings we could take a step down in our pace of asset purchases.” These remarks, which weren’t even Bernanke’s prepared remarks, were the first time any senior Fed official had mentioned the idea of tapering down the bond purchases. Note though that although he floated this idea in May, the Fed didn’t start tapering until December. From its $45bn a month in Treasuries and $40bn in mortgage-backed securities, it “modestly” tapered by $5bn each at the following meetings until finally stopping all purchases in October.

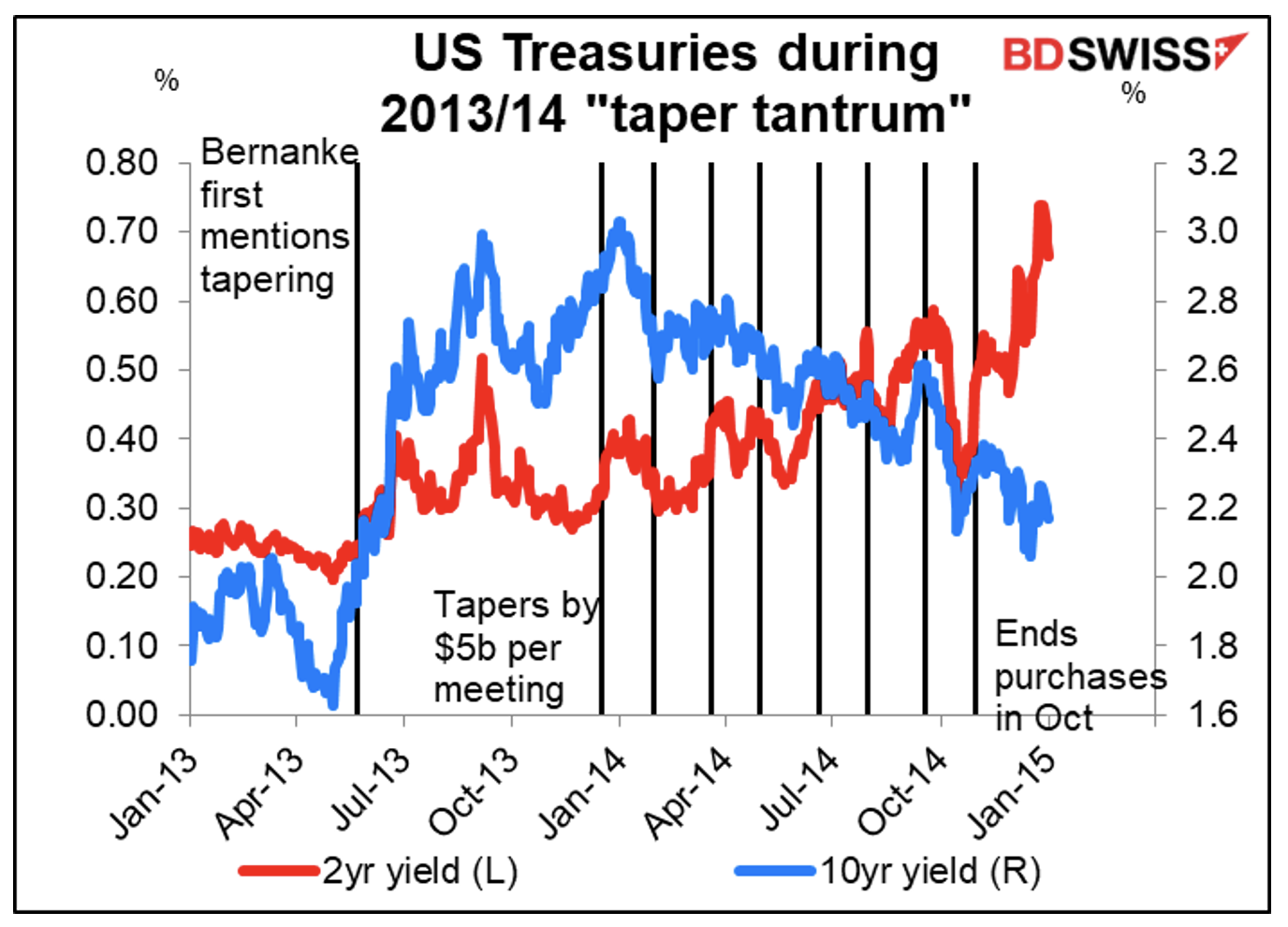

Despite all the talk of a "tantrum," the tantrum seems to have been more about the idea of tapering rather than the reality. Ten-year yields did rise dramatically following Bernanke’s comments, but they peaked shortly after the first cut in purchases. By the time the Fed announced that they were finishing with the purchases, 10-year yields were almost back to where they started from (2.32% vs 1.93% the day before Bernanke spoke). The 2-year yield rose gradually however in anticipation of an eventual hike in the fed funds rate.

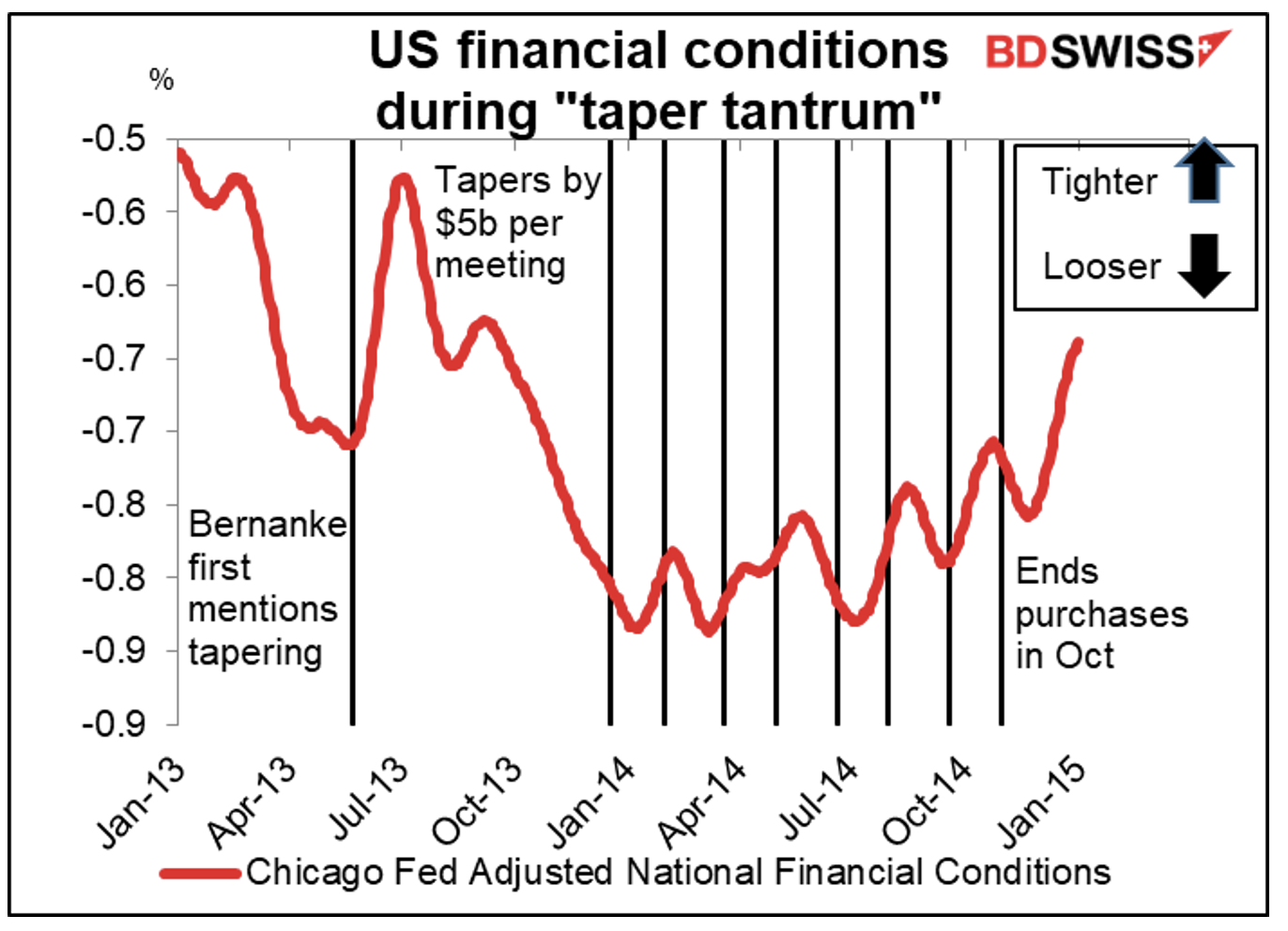

Financial conditions initially tightened sharply on the news, but as the markets settled down, they returned to normal. By the time tapering actually started they were looser than when Chair Bernanke had first broached the subject, and when the purchases ended they were about where they were when the whole process started. In other words, net-net there was no big impact from withdrawing the stimulus.

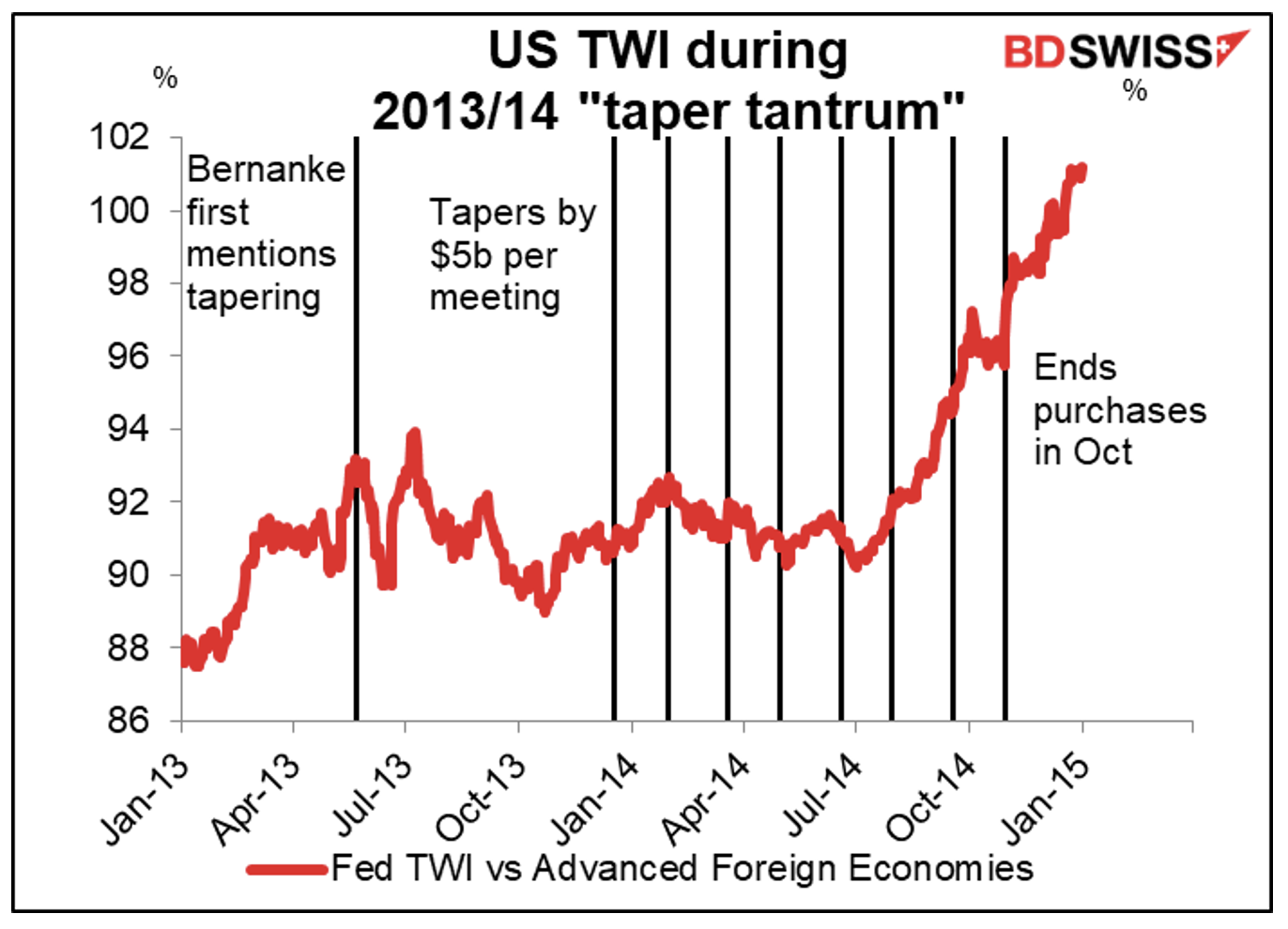

Although one might’ve expected less monetary stimulus to be good for the dollar, in fact the currency initially weakened on the news and didn’t start to gain appreciably until the tapering was more than halfway done.

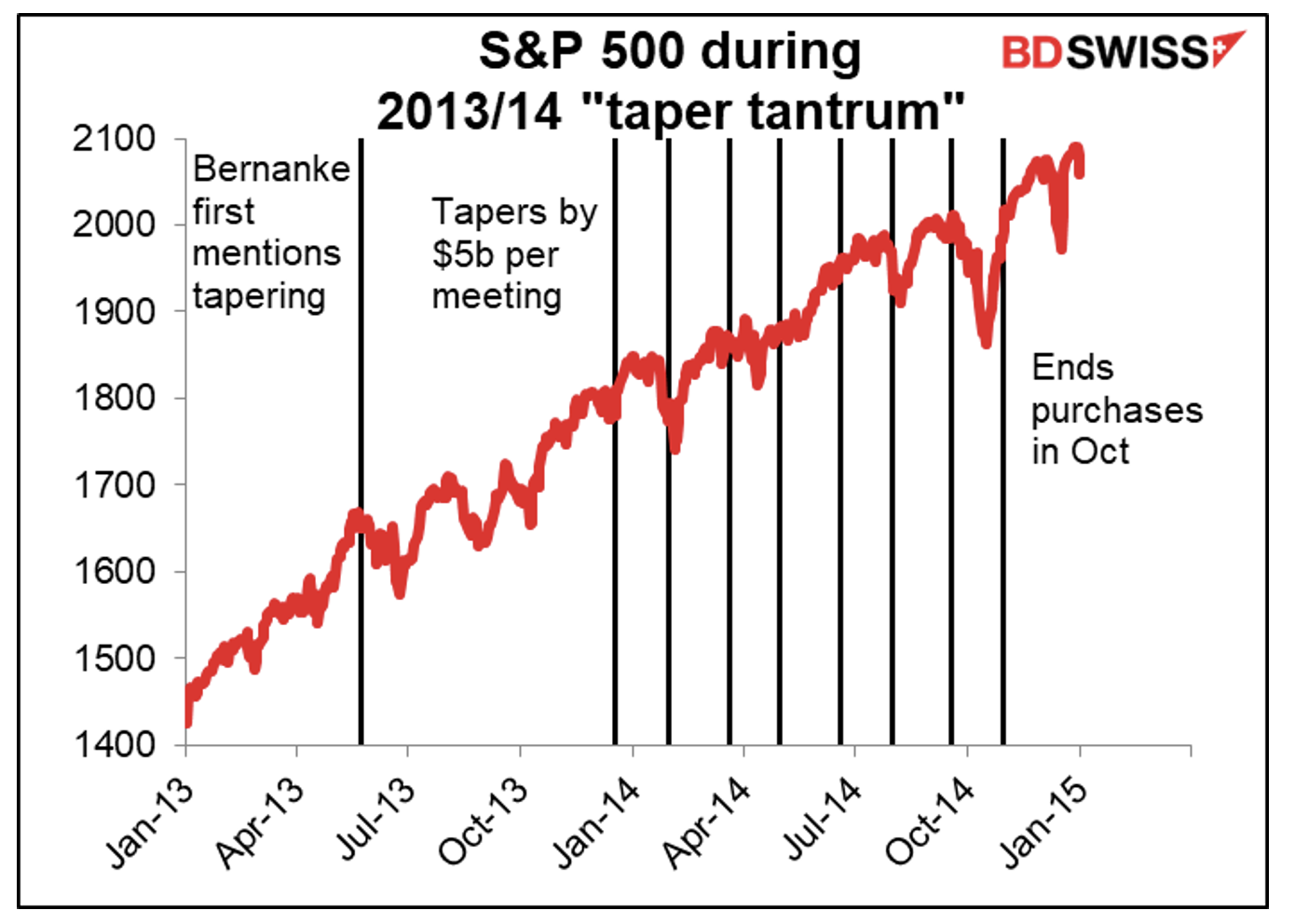

As for the stock market, it initially dipped as one might expect in anticipation of higher interest rates. But the dip proved temporary and the market continued to push ever higher.

The “tantrum” therefore seems to have been more about Fed communication than about Fed practice, because the act of tapering didn’t have that much impact on the long end of the market. In fact, it doesn’t seem to have had much impact on any of the financial markets, except of course the short end of the bond market.

The Fed seems to have learned the lesson. At his press conference following the April FOMC meeting, Fed Chair Powell said that,

“…we’ll continue asset purchases at this pace until we see substantial further progress. And we’re going to communicate well in advance of any decision. We’re going to let the public know that that’s what we’re thinking. And so there’ll be a lot of warning and that kind of thing.”

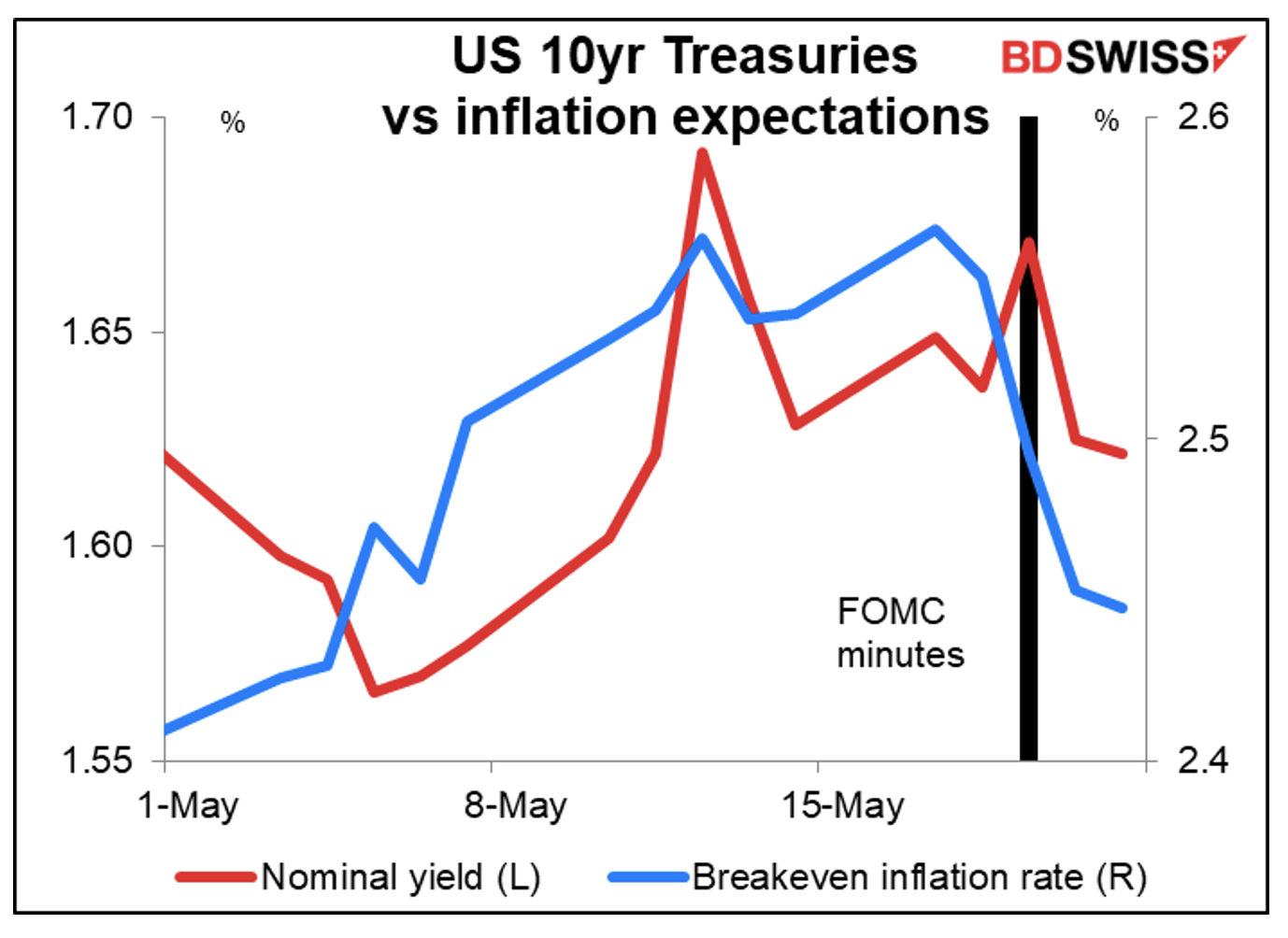

This may be why although bond yields rose sharply following the release of the minutes, they soon moved back down as the market realized that it would be some time before the tapering started and that they’d get adequate warning.

Inflation expectations on the other hand continued to move lower, perhaps because people realized that at least some officials are cognizant of the risk of inflation and are willing to do something about it.

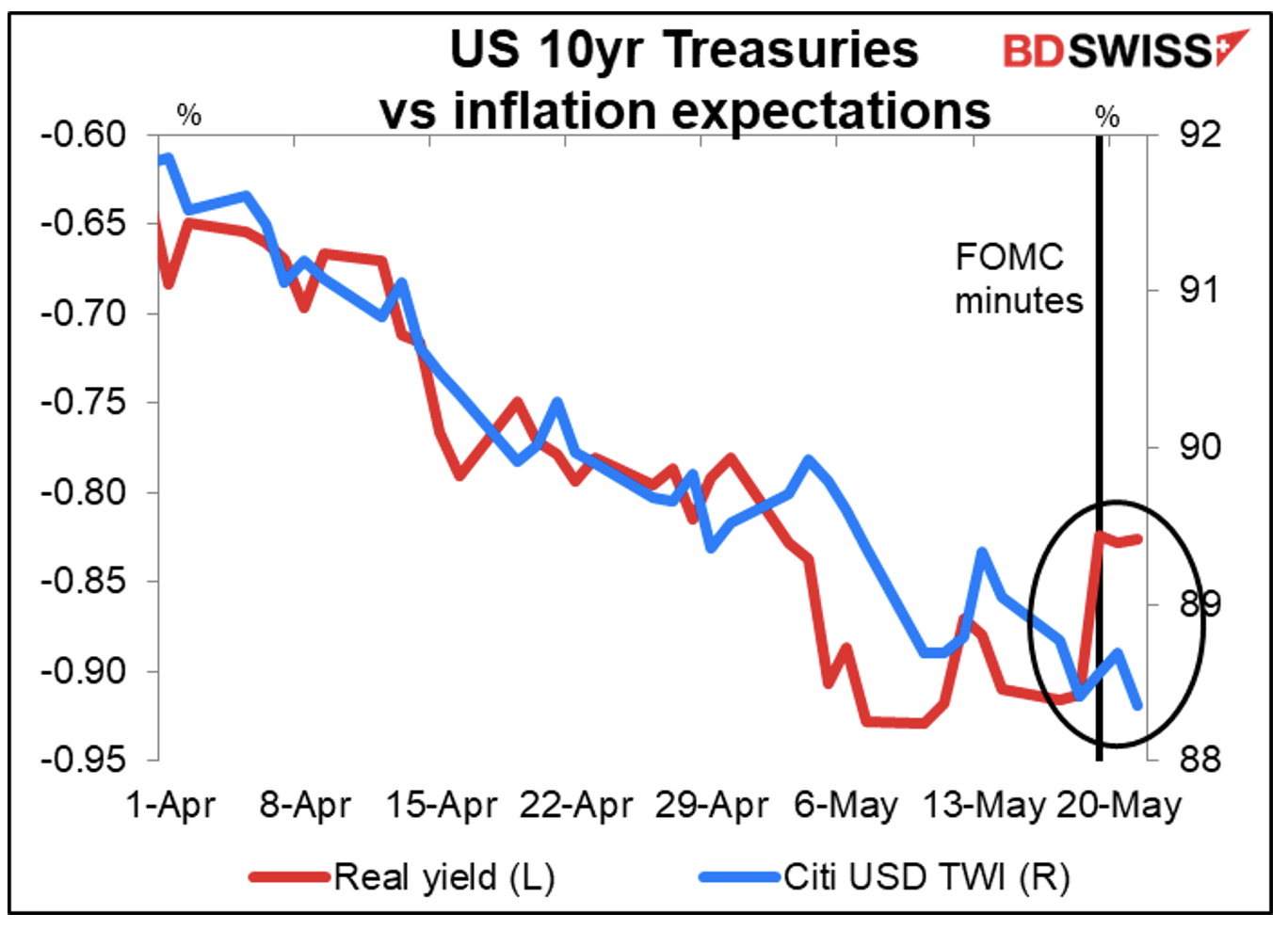

Lower breakeven inflation means higher real yields. Yet that didn’t support the dollar that much immediately.

My conclusion is that not only has the Fed absorbed the lessons of 2013/14, but the market has too: any changes are going to be gradual and not have a major impact on the U.S. economy or markets as monetary stimulus gives way to self-sustaining growth.

The views and opinions expressed herein are the views and opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Nasdaq, Inc.