In my opinion, the most influential “inventions” are tools that save time, money and effort. Historians highlight the domestication of fire and paper as some of the most consequential breakthroughs in human history.

Any list of this sort will include subjectivity. Having lived and worked in/around Chicago for most of my life, perhaps I’m skewed by the well-spring of transformative financial work that transpired around me. I believe the introduction of index funds and the products that evolved in their wake may be added to that venerable list.

In the early 1970s, a handful of Chicago academics and bankers were doing breakthrough work. Today, Jack Bogle is typically credited with advancing the “index fund.” Bogle’s work came right on the heels of breakthroughs by John “Mac” McQuown (Wells Fargo), Rex Sinquefield (American National Bank of Chicago), as well as Eugene Fama, Robert Merton, Fischer Black and Myron Scholes (University of Chicago).

Ultimately, history is written by the victors. In many ways, we all won because of their efforts. Indexing works. Index options can help end users further manage their exposure.

Why It Works

Indexed investing makes a potentially complex process very simple. Market indexes are measurement tools. In the late 19th Century, Charles Dow first published the Dow Jones Transportation Index.

The American economy was growing by leaps and bounds during Reconstruction. The railroad industry was literally paving the way to growth. Charles Dow wanted a way to track the performance of this burgeoning industry.

His “benchmark” provided an easy way to gauge the fluctuations of a group of equities. From that perspective, despite significantly more indexes available today – the output is essentially the same. An index is a way to group and measure performance.

You can’t trade shares of the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway in 2023, but the index still exists. Indexes, like all markets, evolve.

Nasdaq Indexes

In 1971, the Nasdaq Composite Index was established. It continues to track nearly all the stocks listed on the Nasdaq stock exchange (roughly 2,500 securities). The Nasdaq-100 ® Index (NDX) followed in early 1985. Both measures are market cap weighted and track securities from a variety of sectors. The NDX has become a shorthand way of referring to the global Information Technology market, but it also includes Consumer Discretionary, Health Care, Materials, Industrials and Utilities.

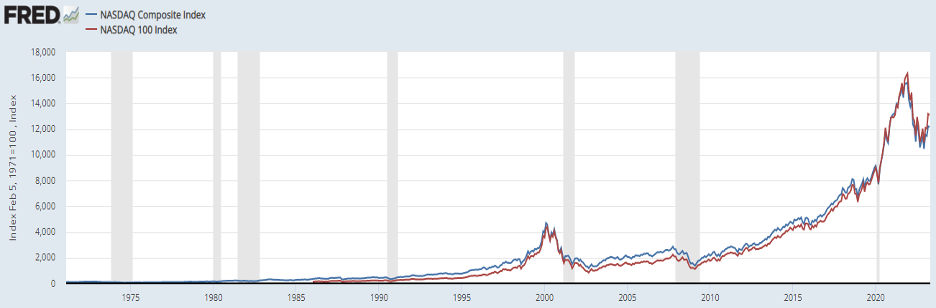

Going back to our point on why it “works,” the key is the fact that over long-time frames, most indexes increase in value. This visual shows the value of the Nasdaq Composite and NDX set to a 100 base, since inception(s):

It’s been a very positive 52 years for the Composite and 38 years for the NDX.

Solve Problems

Prior to the introduction of index funds, all fund vehicles were actively managed. Asset managers crunched numbers and courted big money. They allocated to specific companies and areas of the market. Execution costs and turnover were both much higher than what the modern market is accustomed to.

These funds had significant overhead, so the fees investors paid to own them were relatively high. Beyond that, the data showed that, over time, the active money managers were underperforming relative to these equity benchmarks (indexes).

So, you have positively skewed equity returns, but high costs and imperfect managers. How could that be improved upon?

Why not create a vehicle designed to passively track the performance of those equity indexes with very low turnover?

In 1971, John “Mac” McQuown and some of the University of Chicago wonks did just that with about $6 million in assets earmarked for the Samsonite pension plan. Other pioneers like Jack Bogle improved the process in the middle of the decade, and it worked.

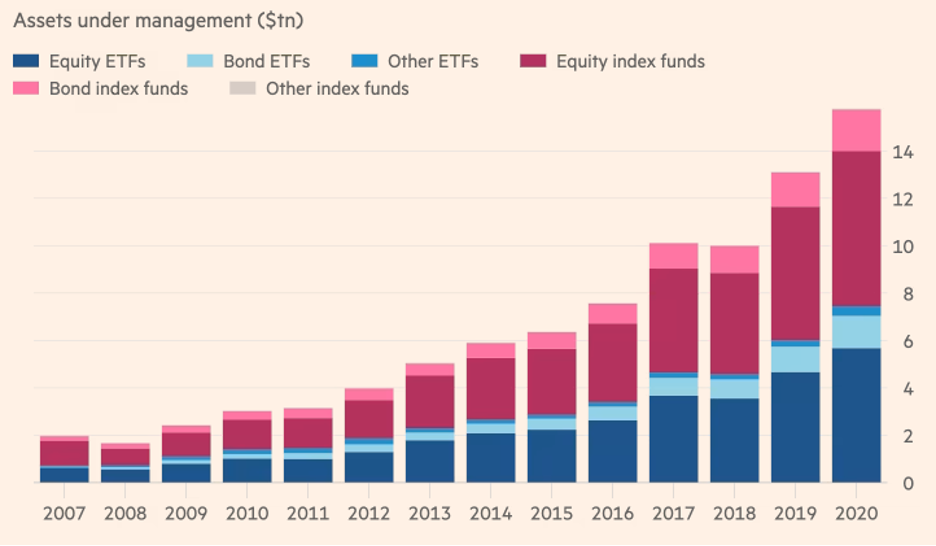

Trillions are now allocated to passive funds like mutual funds and ETFs, designed to replicate the performance of the Nasdaq Composite, NDX and other U.S. equity indexes. It’s created a self-reinforcing virtuous cycle with positive performance and low-fee structure.

This visual is slightly dated, but it shows the growth in AUM around indexed products between 2007 and 2020. As you can see, most capital flows to equity ETFs and equity index funds. Current estimates for the aggregate AUM come in at ~$20 trillion.

The Invesco QQQ Trust is “a unit investment trust with an objective to provide investment results that generally correspond to the price and yield performance of the NDX.” The QQQ fund now has assets under management of around $171.5 billion.

The Byproducts of Innovation

The derivative markets wouldn’t exist without underlying markets from which to price forward-risk management tools. There would be no crude oil futures without a spot market. There would be no Microsoft, Apple or Tesla options without those securities trading on exchanges.

Financial futures contracts came into existence in the early 1970s as well. Currency futures were introduced in 1972 and interest rate futures in 1975. By the early 1980s, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) looked to continue its success in financial futures when it launched stock index futures contracts (1982).

Shortly thereafter, index options were born (also launched in Chicago) in 1983. The first index options were linked to the performance of the S&P 100 Index. Today, there are around 50 index options products, including those tethered to the NDX like Nasdaq-100 Micro Index Options (XND).

Financial futures are unique from the historically physically dominated futures contracts. These products needed to be cash-settled as opposed to physically deliverable. Similarly, there are a few unique attributes associated with index (non-equity) options.

What’s an Index?

Let me start answering the question with another question. What makes for a great apple pie? In my opinion, a great pie requires excellent ingredients.

Let’s imagine there are ten things that go into the “perfect” apple pie recipe. They are all in different ratios. That’s pretty much how an index is constructed. There’s a recipe.

In the case of the NDX, the recipe evolves slightly as capital markets and money flows change. The index is reconstituted once a year in December. The NDX is a modified market-cap weighted index designed to measure the performance of the 100 largest Nasdaq-listed non-financial companies.

Let’s imagine Piñata apples are like financials. They are excluded from the recipe. No piñata apples in this recipe.

Here’s how the different sectors (or recipe components) break down for 2023 (as of late April):

The Information Technology sector is like the fruit in our apple pie. It’s star of the show. Ironically, Apple Corporation (APPL) is the second largest constituent (12.63%) in the index, surpassed only by Microsoft Corporation (MSFT) with 12.66% weighting. Amazon (AMZN), which is considered Consumer Discretionary, is the third largest component (6.33%).

Further down the list (weighting terms), you have companies like Starbucks (SBUX) and Dollar Tree (DLTR). They are like the cinnamon and sugar. They diversify the flavor profile.

However, one key characteristic of an index is that it’s designed to measure. Indexes are not tradeable instruments like securities (single name equities) and ETFs because they cannot be “delivered” in the same way as 100 shares of AAPL or QQQ. It would be far too capital-intensive and messy to deliver shares of 100 stocks in the perfect ratio, but index options arguably solved that issue.

Index Options

For the past ~40 years, there have been options available on index products. There are calls and puts that trade very actively and afford end users exposure to the price levels of the reference asset – like the NDX.

Similar to the Financial Futures that were pioneered in the early 80s, Index options are cash-settled instruments. So, if held until expiration, an in-the-money (ITM) index option will simply settle to its cash value at expiration. An example should make this clear.

Let’s imagine you took a position targeting the NDX, moving higher by the end of Q1. To facilitate this exposure, you chose to buy an NDX 12,750 call with a March 31 (2023) expiration. For the sake of example, let’s say you purchased the call option for 50.00 (or $5,000).

The maximum risk on any outright long position is the premium paid. In this case, that’s $5,000 plus any frictional costs. If held until expiration, the position would be profitable with a settle above 12,800 (strike plus premium paid). The option would have an economic value anywhere above 12,750.

The NDX settled at 13,181.30 on March 31. You can check the settlement values for all non-standard NDX options using the ticker ^XQC.

The value of any ITM index option is simply the difference between the strike price and settlement value. In this case:

13,181.30 – 12,750.00 = 431.30

On March 31, the expiring 12,750 call was worth 431.30. Since each NDX option governs 100 units, we multiply the settlement value (431.30) by 100 to figure out the cash value ($43,130). Following expiration, that cash value will settle in your account. Relative to the $50.00 paid for the option, this hypothetical example was profitable by [(431.30 – 50.00)*100] $38,130.

Instead, let’s imagine that the NDX closed at 12,755.00 at the end of March. In that case, the trade would not be profitable because in our example we paid $50.00 for an option that settled worth $5.00. So, net-net, the position would lose $4,500. The key distinction relative to a standard equity or ETF option is that no shares are delivered for ITM options. They always settle in cash.

Let’s contrast that to QQQ options, which are physically delivered.

What happens if you owned a 300 strike call that expired March 31st on QQQ?

Well, the QQQ ETF settled at $320.93 at the end of the month. So, the 300 strike calls were worth $20.93. If you paid less than that to purchase the option, you’re profitable on paper. If you paid more, you’re still underwater. The difference is that following expiration, $30,000 will come out of your account to cover each long call option because you’re obliged to purchase 100 shares of QQQ at the strike price.

In this situation, you’re now long on the underlying shares of the ETF until you close the equity position. So, there is a “go-forward risk.” There is no directional exposure post-expiration with cash-settled index options. Furthermore, the NDX exposure wouldn’t require the $30k (in our example) in an account to cover the securities purchase.

Some option users prefer to only manage options exposure. Others are comfortable assuming underlying securities positions as well as options. There is no “right way,” but understanding what happens to a derivative product at expiration is important in either case.

European-Styled

There are a couple of other idiosyncratic differences between index and equity options. For example, nearly all index options are European-styled. That simply means that index options cannot be exercised or assigned ahead of expiration.

By contrast, all equity (single-name securities and ETF) options are American-styled. As a result, those options can be assigned/exercised at any point on or before expiration. Call options that are ITM may be exercised early to capture a dividend payment. In unique situations, a put option might be exercised ahead of expiration for balance sheet reasons (interest payments on a short stock position after factoring in potential dividends).

Granular Expiries

Option volumes have grown significantly in recent years. That’s in part due to the demand for more short-dated options. Since 2022, the major U.S. index products have been available with daily expirations. In other words, there are NDX options that settle every business day looking out for five weeks.

Historically, options for indexes as well as equity products, expired on the third Friday of the month. Years ago, weekly index options were introduced, so there were NDX options that expired every Friday. More recently, the industry introduced index options with daily expirations because end users wanted to be able to craft very specific exposure and have the flexibility to protect against known unknowns like a Federal Reserve meeting or inflation data.

Tax Treatment

The last idiosyncratic difference between index options and standard equity/ETF options involves their treatment in the eyes of the Internal Revenue Service.

Here’s a piece dedicated to the topic of index option taxation to learn more.

Recap

We covered a lot in this piece so let’s recap and reinforce.

- Indexed investing has become increasingly favored by individuals and institutions over the past few decades.

- Lower fee structures, long-term outperformance, and a wide variety of products benchmarked to major indexes helped advance this trend.

- Indexes are designed to measure the performance of a group of assets, but they are not investable/tradeable.

- Innovative individuals and companies created tradeable products like mutual funds, ETFs, financial futures and index options to help facilitate the growth in indexed investing.

- Indexes vary but have a specific methodology and their constituency changes over time.

- Index options are designed to give end users exposure to (typically 100 units) a broad-based index like the NDX.

- There are some important differences between standard equity options and index options including styling, settlement, expiries and potential tax treatment.

The views and opinions expressed herein are the views and opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Nasdaq, Inc.