Experience is a generous teacher; she gives us lots of opportunities to learn from our mistakes. If I’m to be objective, most of my mistakes occurred because of – let’s be tactful – incomplete analysis of the situation. (AKA stupidity). But last Friday I made what may have been a first for myself: I was too smart. What I learned from that is, in the short term, it doesn’t pay to be smarter than the market. In trading, you’re trying to figure out what the other guy is going to do, not what he or she should do.

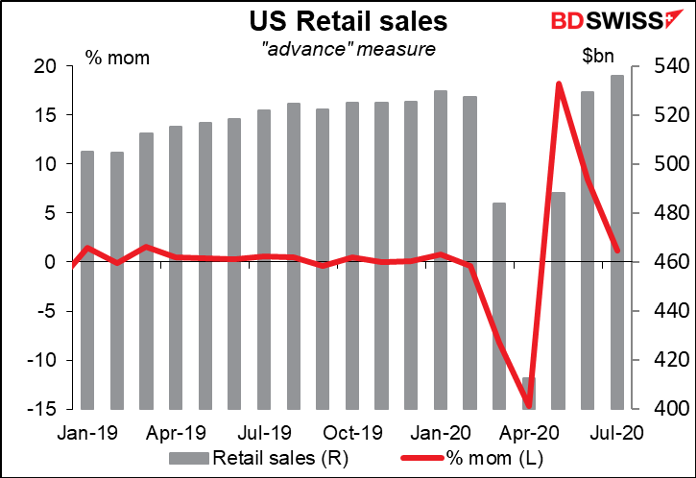

The issue was last Friday’s U.S. retail sales. The market consensus was that sales would be up 2.1% mom. Instead, they were up only 1.2%. Disappointing! Sell! Sell!

But wait a minute (I thought)…the previous month was revised up to +8.4% mom from +7.5% mom initially. I ran the numbers and found out that, much to my surprise, the figure had actually beat the market estimate! The consensus 2.1% mom rise would’ve resulted in retail sales hitting $535.3bn for the month, but in fact they were $536.0bn – slightly better! Go Marshall! Great analysis! Let’s get that out first, get your clients in, and wait for the market to catch up to you!

Only…the market didn’t. Nobody else thought that way. Everyone was looking for a 2.1% rise and when they only got a 1.2% rise, that’s all that mattered. For example, the economist at investment bank Morgan Stanley wrote, “The July retail sales report was positive, showing moderate growth, but was below expectations. Headline sales were below consensus, up 1.2%M in July, with June upwardly revised 90bp to 8.4%.”

My mistake could’ve been worse. In the event U.S. stocks closed almost unchanged. No tragedy, but hardly the analytical triumph I had expected.

What went wrong? John Maynard Keynes likened the stock market to a fictional contest in which entrants are asked to choose the six most attractive faces from a hundred photographs. In such a game, the winning strategy won’t be to choose the six that you think are the most attractive, but rather the ones that you think the rest of the entrants will think are most attractive – bearing in mind of course that the other entrants are also doing the same. "It is not a case of choosing those [faces] that, to the best of one's judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those that average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practice the fourth, fifth and higher degrees." (Keynes, General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, 1936).

In this kind of “Keynesian beauty contest,” it doesn’t pay to be too smart (not that this is often a problem for me, I have to admit). For long-term investors, the whole idea is to outsmart the market and see an opportunity that no one else does. But that doesn’t necessarily work in trading.

Another real-life example comes to mind from my experience long, long ago. Back in 1984, Britain was a major oil exporter and the pound traded as a petrocurrency, much as NOK or RUB does today. One day Mexico raised the price of its oil. GBP immediately jumped.

I was a financial reporter back then. My colleagues and I started laughing. The reason Mexico was raising the price of its oil was that the British coal miners were on strike and British power stations were importing large quantities of heavy, sour Mexican crude oil to burn in place of the domestic coal that was no longer available. This action would dent Britain’s trade balance while doing nothing to boost the price of the light, sweet crude that Britain exported. It was unambiguously bad for the pound. But the forex market didn’t understand oil and didn’t care about such details. Higher oil prices = higher pound was the market’s immediate reaction. Buy GBP!

Over time of course the implications of the move would become clear as the country’s trade balance deteriorated and the pound (presumably) weakened. A long-term investor – pension fund manager, life insurance fund manager, etc. – would have done well to fade the market in such a situation. But would a trader who had sold GBP/USD on the news – as he or she should’ve – still have had a job by that time? I’m not sure.

Moral of the story: trading isn’t investing. In trading, it pays to be smart, but not necessarily smarter than everyone else.

The views and opinions expressed herein are the views and opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Nasdaq, Inc.